This article is intended only for general informational purposes. VMG Health is not rendering tax, accounting, financial, or other professional advice through this article. This article is not intended to replace such professional advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any action or decision which may affect your business or your tax planning. The reader is encouraged to consult with a qualified tax professional should they have further questions about the subject discussed in this article and should consult a qualified professional advisor before making any decision or action involving their business. VMG Health shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person who relies on this document.

Executive Summary

When President Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (“TCJA” and also referred to as the “2017 Tax Act”) into law on December 22, 2017, many major shifts in the U.S. tax system were triggered. Among the most significant of those shifts was a decrease in the corporate tax rate applicable to C-Corporations (“C-Corps”) and the addition of a Qualified Business Income (“QBI”) deduction for S-Corporations and entities treated as partnerships for tax purposes (collectively, “pass-through entities” or “PTEs”). For many owners of ambulatory surgery centers (“ASCs”) which are currently structured as PTEs, the decrease in the corporate tax rate may look at first glance to be an attractive incentive to convert from a pass-through structure to a C-Corp structure to take advantage of the new lower C-Corp income tax rate. Below we’ll take a look as to why that may not be the case when looking at the broader tax picture and other tax considerations for owners of ASCs to consider resulting from the TCJA. We’ll also quantify the discussion through comparative analysis of the taxability of a hypothetical ASC under the TCJA if taxed as a C-Corp or as a PTE.

Entity-Level Taxes

The primary tax reform-related change that has many ASC investors inquiring about the C-Corp structure has been the decrease in the statutory federal tax rate applicable to C-Corps from 35% to 21%. Prior to the passing of tax reform, the United States had the highest combined (federal and state) corporate income tax rate among Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (“OECD”) nations at 38.9%, exceeding the OECD average excluding the U.S. by approximately 15 percentage points (1500 basis points). As a result of the TCJA, the combined federal and state statutory tax rates on C-Corps will average 25.7% across all states, in line with the OECD average[1].

PTEs in the United States, in contrast, face no entity-level taxes. Instead, all taxes paid by PTEs in the U.S. are paid by their owners at the individual-level tax rates.

Individual-Level Taxes

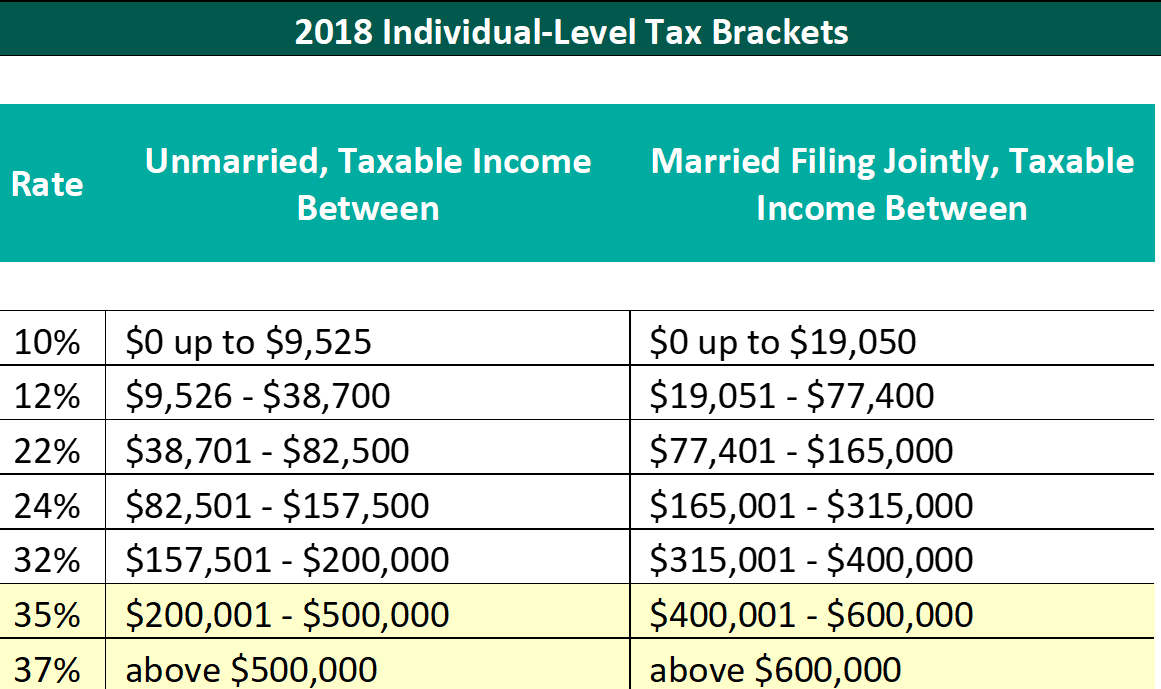

Taxes on PTEs are paid by individual owners of those entities via allocations of the entity’s net taxable income to its shareholders/partners based (generally) on relative ownership percentages (PTEs often have special allocations to certain shareholders for a variety of tax attributes which may result in allocated net taxable income to any particular partner not equaling the partner’s capital ownership percentage times total PTE net taxable income). These pro-rata allocations are then taxed at the federal and state income tax rates applicable to each individual shareholder/partner. For 2018, the applicable individual federal income tax rates range from 10% – 37%. We expect that most ASC individual investors will likely face tax rates of 35% – 37% (plus any state-level taxation) in 2018, an amount based on ordinary income (non-capital gains income) from all sources, not solely those from the entity in question. The full 2018 tax brackets and rates are as follows[2]:

Comparing these individual-level pass-through rates to the new corporate rates under the TCJA, it’s easy to see why many investors are exploring a conversion to C-Corp status. C-Corp investors, however, also face an additional individual-level tax on dividends received from the C-Corp. Whereas PTE investors are taxed only once and are taxed on all income earned by the business, whether distributed to shareholders/investors or retained by the entity, C-Corp profits are taxed twice: once on profits earned by the entity, and a second time on dividends paid by the entity to its investors. We expect most ASC investors are familiar with this “double-taxation” concept; it’s a primary driver behind most privately held businesses in this country electing to use a PTE structure. For 2018 under the TCJA, the maximum tax rate on qualified dividends will remain at 20%, ranging from 0 – 20% depending on the individual’s taxable income.[3] Non-qualified dividends are taxed at ordinary income tax rates.[4]

Other Taxes

In addition to the common entity-level and individual-level taxes outlined above, investors in ASCs organized as either C-Corps or PTEs may face one more layer of tax depending on which entity structure is chosen.

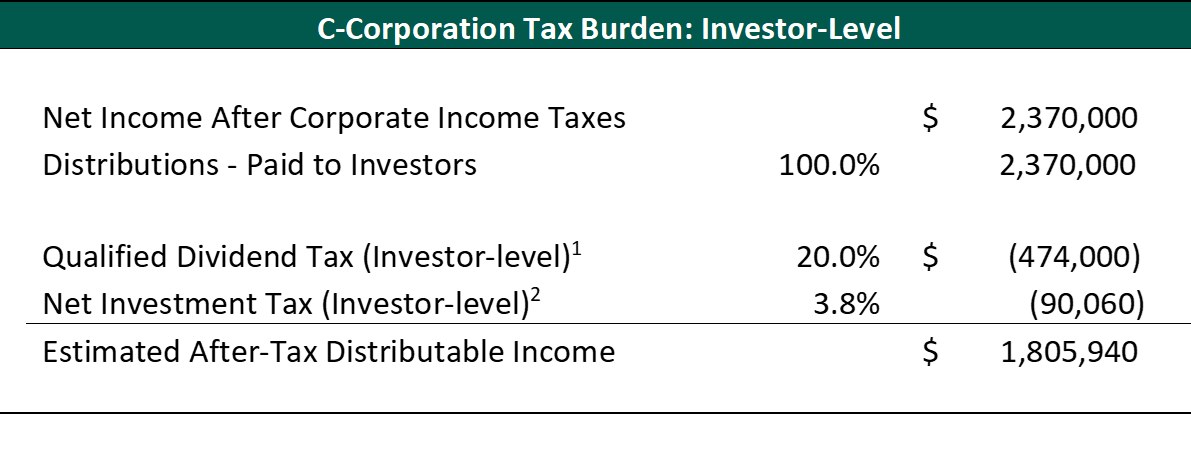

C-Corp investors earning more than $200,000 if single or $250,000 if married filing jointly may face an additional 3.8% net investment income tax on dividends received from their C-Corp entity. This amount will apply whether the investor is involved in the operation of the ASC or not.[5]

Qualified Business Income (“QBI”) Deduction for PTE Investors

An intriguing provision resulting from the TCJA is the ability for investors in PTEs to take a 20% deduction of taxable income for qualified business income under Sec. 199A of the Internal Revenue Code (“IRC”), which would reduce the effective tax rate for ASCs organized as PTEs to as low as 29.6% (i.e. 37.0% x 80% = 29.6%).

There is an exemption for the QBI deduction, however, for certain businesses involving professional/personal services as defined by Provision 11011 of Section 199A:

Specified service trade or business (SSTB), which includes a trade or business involving the performance of services in the fields of health, law, accounting, actuarial science, performing arts, consulting, athletics, financial services, investing and investment management, trading, dealing in certain assets or any trade or business where the principal asset is the reputation or skill of one or more of its employees

This exemption prevents the owners of the businesses listed above from fully taking the QBI deduction if such owners have taxable income from all sources greater than $157,500 (individuals) or $315,000 (married filing jointly); taxpayers making over these thresholds will have a phased-out ability to take the QBI deduction from $315,000 to $415,000 for joint filers and $157,500 to $207,500 for all other filing statuses. As such, we expect most ASC investors (but not all) will not be eligible for the QBI deduction as health services are explicitly excluded from eligibility for the QBI deduction.

Upon review of the primary mechanics of taxation for both C-Corps and PTEs, the attractiveness of a conversion from a PTE to a C-Corp is somewhat diminished, but which entity structure to employ may still be unclear. In the following section we’ll attempt to put some numbers to the story in the search for tax status clarity.

Case Study

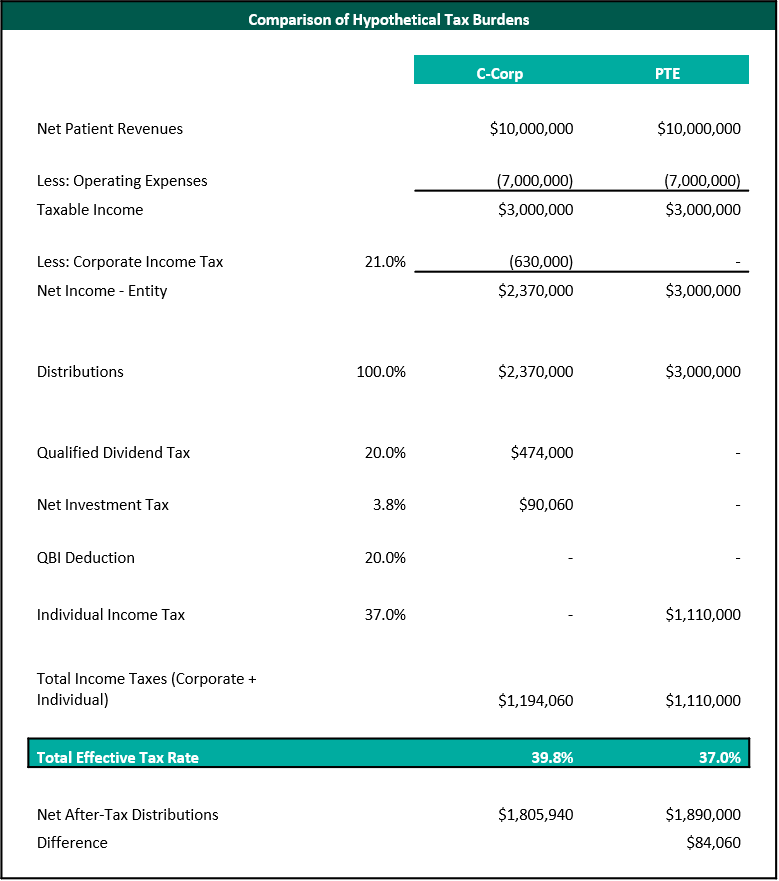

We discussed above some of the issues in considering a change in taxable status for ASCs from a pass-through entity structure to a C-Corporation structure. In the following case study, we’ll take the information discussed above and apply it to an analysis of a hypothetical ASC which generates $10 million in annual net revenues and $3 million in taxable income, and distributes 100% of taxable income to its individual, non-corporate owners.

C-Corp Scenario

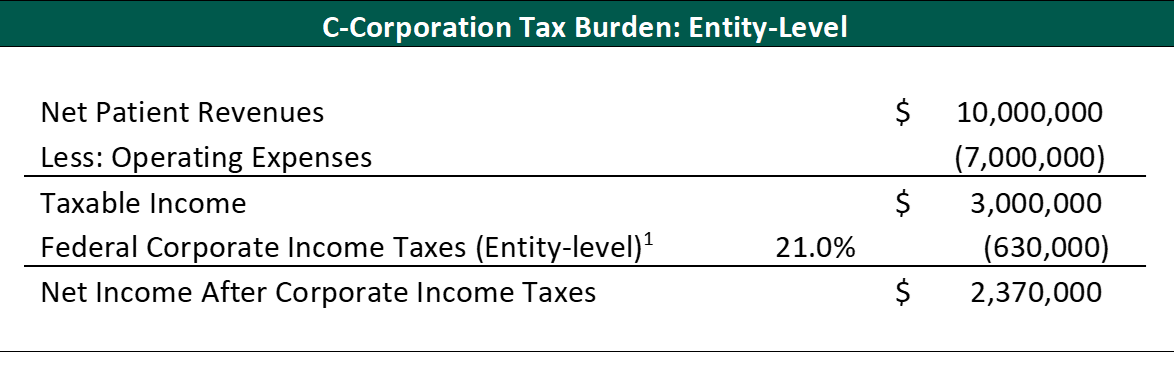

The hypothetical ASC as described above and structured as a C-Corporation may face the following tax burdens:

21% corporate tax rate on taxable income of $3,000,000 to be paid by the entity:

The 23.8% tax on qualified dividends/distributions (20.0% qualified dividend tax plus 3.8% net investment income tax to be paid by the ASC’s investors):

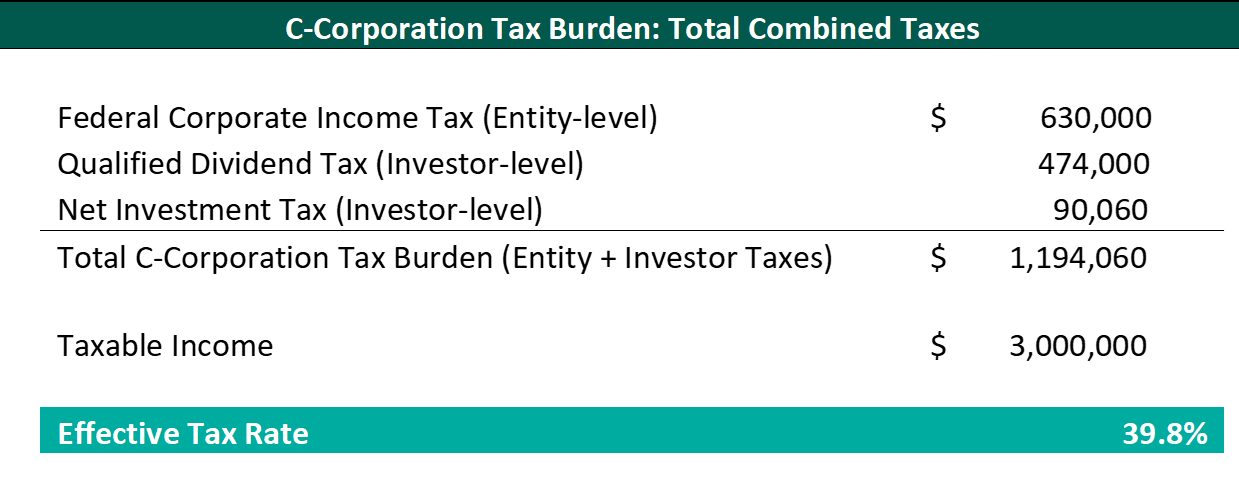

In summary, the C-Corp and its investors face a total of $1,194,060 in federal taxes on $3,000,000 of taxable income, which results in a combined (entity + investor) effective income tax rate of 39.8%:

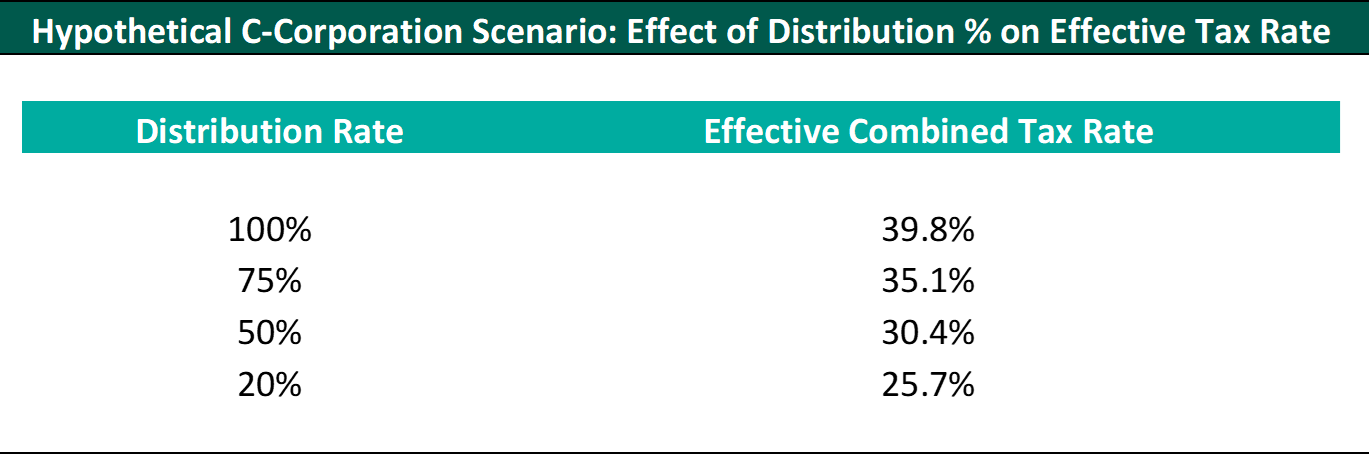

We recognize that most ASCs may not distribute 100% of earnings to their owners, as some quantity of funds for capital expenditures, working capital, and debt service costs may need to be retained for operations. As such, below is a sensitivity table measuring the effective tax rate on the hypothetical ASC described above across a range of distributions as a percentage of the C-Corp’s earnings:

It is evident that entities which make little in the way of distributions will face significantly lower effective combined tax rates as a C-Corp. It is our experience, however, that most ASC investors prefer to receive regular and substantial dividends from their investments in ASCs.

Additionally, we must caution against the use of accumulating and not distributing earnings as a tax planning strategy. At best, limiting distributions will only defer tax burdens, not eliminate them. This can be a useful tool, but the effectiveness of such strategies will generally be diluted by tax penalties which are designed to prevent such accumulation of profits. C-Corps which accumulate significant cash can become subject to two tax penalties[9]: accumulated earnings tax and personal holding company tax. The calculation of such taxes is beyond the scope of this article, but these penalty taxes are designed to incentivize C-Corps to distribute to shareholders cash amounts which are beyond the reasonable cash needs of the business.

Pass-Through Entity Scenario

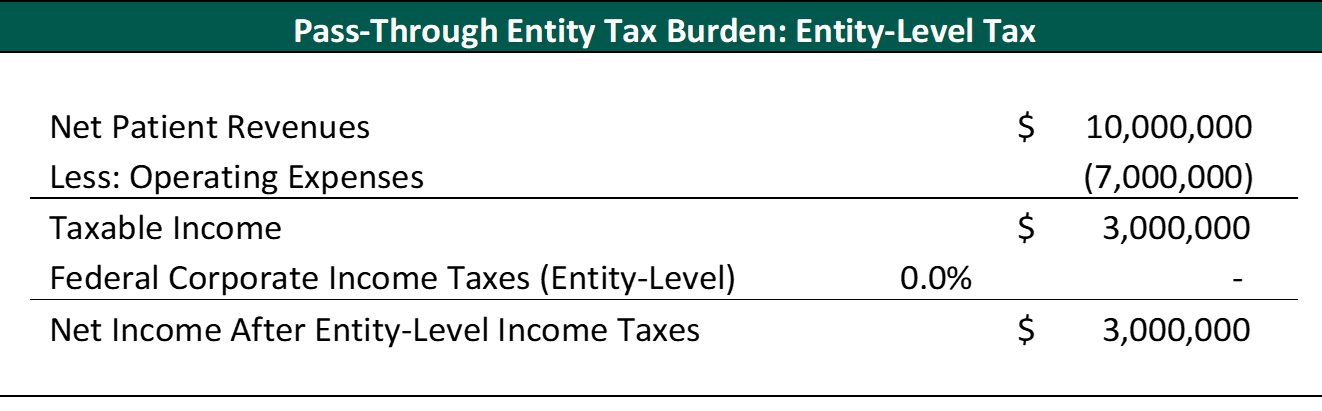

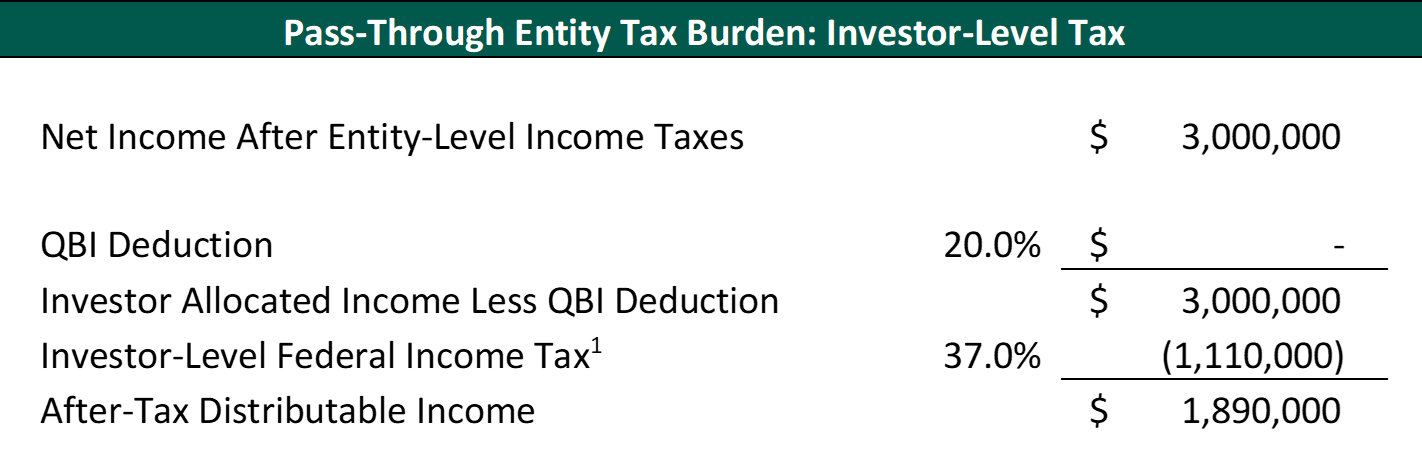

The same hypothetical ASC as described earlier but structured as a pass-through entity may face the following income tax burdens:

No entity-level tax burden on taxable income of $3,000,000:

A 37% individual-level income tax rate, and no deduction for QBI:

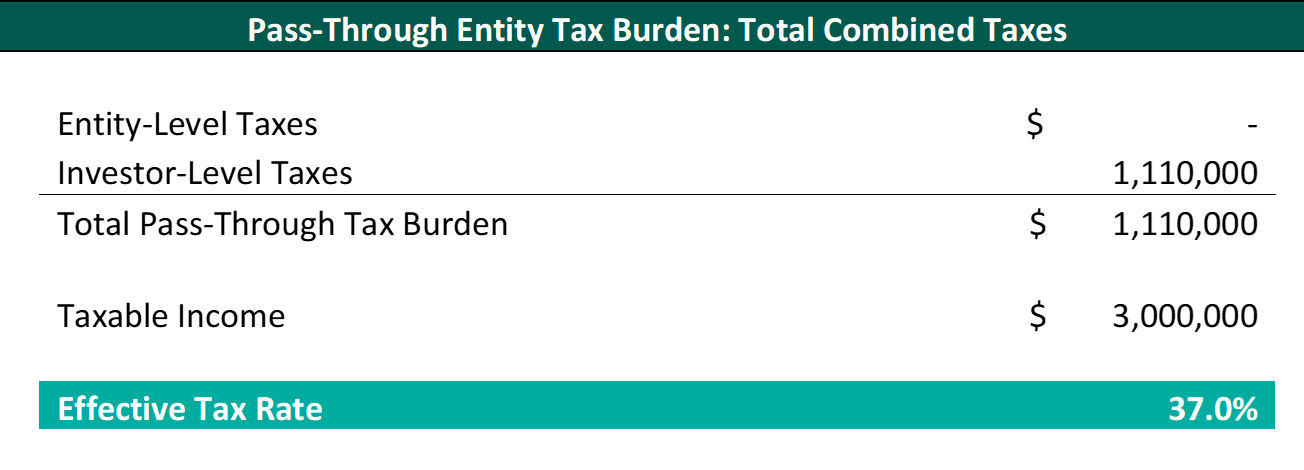

In summary, the PTE’s investors face $1,100,000 in federal taxes on $3,000,000 of taxable income, which results in a combined effective tax rate of 37.0%:

Therefore, in this hypothetical ASC, the estimated total effective income tax rate is 39.8% for a C-Corp investor, vs. 37.0% for a PTE investor. As a result, an investor in the hypothetical ASC taxed as a PTE would save approximately $84,060 in taxes as compared to an investor in an otherwise comparable ASC structured as a C-Corp. Stated differently, investors in this hypothetical ASC example would receive $84,060 more (or 4.4% higher) in net after-tax distributions if the ASC were structured as a PTE vs. a C-Corp.

We note that for shareholders/partners who qualify for the QBI deduction, the effective tax rate for PTE investors may be even lower as discussed previously. We also note that for physician-owners who assist in the day to day operations of the ASC, the effective tax rate may be higher than calculated here due to self-employment taxes.

We also note that for purposes of this hypothetical example, we have ignored all state income taxes (both for C-Corps and individuals) and have applied the maximum tax rate for individuals and qualified dividends. We highly recommend that any tax-status analysis performed for the purposes of considering a tax-status conversion be based on the tax attributes specific to the subject entity and its individual investors.

Finally, we must also acknowledge that there can be meaningful tax consequences as a result of a taxable entity conversion. Given the complexity and entity-specific nature of these consequences, however, measurement of such taxability is beyond the scope of this article.

In the following table, we present a side by side comparison which shows that even under the lower corporate tax rate and new provisions of tax reform, PTEs still hold a mild edge on effective tax rates over C-Corps due to the continued existence of the double-taxation regime on businesses organized as C-Corps:

Taxes Upon Sale

While this article is solely focused on the estimated income taxes related to earnings in the course of operations of a hypothetical ASC with assumed characteristics of individual investors, a significant divergence in taxability between C-Corps and PTEs exists when discussing the taxability of proceeds received upon the sale of the business. Unfortunately, due to the complex nature of transaction-related tax calculations involving items such as special allocations, depreciation recapture rules, and other investor or entity-specific assumptions, an analysis of the tax burden to investors upon the sale of their interest in an ASC is beyond the scope of this article. We recommend, however, that the reader of this article give this important issue due consideration when considering the ramifications of a tax-status conversion.

Conclusion

While the decrease in the federal corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21% under the TCJA may appear to provide an incentive for ASCs currently organized as PTEs to make a conversion to C-Corp status, particularly for ASC investors who pay individual income taxes at the top marginal rate of 37%, we find that the double-taxation regime imposed upon C-Corp earnings is simply too burdensome to provide a significant tax savings over PTEs in our simplified hypothetical ASC model, even at a 21% corporate income tax rate. While there may be some non-tax benefits to a C-Corp structure, based on our hypothetical example, a C-Corp structure may not provide a conclusive, significant tax benefit over the pass-through entity structure favored by most current ASC investors. Furthermore, a taxable entity conversion may require significant financial costs (tax and legal advisors), tax costs (possible triggering of tax burdens as a result of conversion and/or at a later sale of the business), and human capital costs (time, effort, and toil of the entity’s managers and investors), further diminishing or clouding the attractiveness of such a strategy.

[1] Tax Foundation https://taxfoundation.org/us-corporate-income-tax-more-competitive/

[2] Tax Foundation https://taxfoundation.org/2018-tax-brackets/

[3] Charles Schwab https://www.schwab.com/public/schwab/investing/retirement_and_planning/taxes/current-rates-rules/dividends-capital-gains-tax-brackets

[4] Wall Street Journal ‘The New World of Taxes: 2019’

[5] Section 1411 of the Internal Revenue Code

[6] For simplicity we are excluding any state income taxes, which vary from state to state.

[7] The actual tax rates applied at the investor level may vary depending on the tax attributes of each individual investor. For simplicity, we are applying the maximum tax rate

[8] Ibid.

[9] Internal Revenue Code Section 531 and 532, Section 542

[10] In contrast with C-Corp individual investors, who pay individual income taxes on dividends paid, PTE investors pay individual income taxes on the PTE’s taxable income regardless if the earnings are actually distributed to its investors. State income taxes, which vary from state to state, have been excluded from this example for the purpose of simplicity.