The Importance of Investing in Ambulatory Surgery Center Nurse Leadership

Christa Shephard

July 1, 2024

Effective October 8, 2024, Carnahan Group has joined VMG Health. Learn more.

September 19, 2024

Written by Christa Shephard

In today’s workplace, employee engagement has hit a standstill. Recent Gallup polls show that many employees have become increasingly detached, leading to a phenomenon known as the “Great Detachment,” which is exacerbating burnout among healthcare professionals. In the sixth episode of Coachify Over Coffee, our certified leadership coaches Laura Baldwin and Savory Turman discuss the importance of coaching in combating disengagement among healthcare professionals.

Employees are showing up, clocking in, and collecting paychecks, but they may not be engaged in meaningful ways. The Great Detachment is not just about productivity—it’s also impacting overall employee wellness, both mentally and physically. It has a ripple effect, reducing organizational growth and employee satisfaction. This phenomenon is particularly troubling in healthcare, where staff engagement is critical to patent care and safety. As healthcare workers become more detached, healthcare organizations face lower job satisfaction among staff, higher turnover rates, and a decline in the quality of care provided. In , The Real Impact of Leadership Coaching, Baldwin and Turman dive into the data that may hold the key to alleviating disengagement at work.

According to a recent study, individuals who work with a coach experience 2.9% faster growth in their careers. Coaching provides the guidance and tools necessary to help employees re-engage with their work and, more importantly, their own professional development. Interestingly, only 23% of surveyed business professionals wanted their managers to serve as their coaches, while 56% preferred instructor-led coaching. These preferences illustrate the need for structured coaching programs that go beyond traditional, managerial feedback.

One of the many concerns stopping individuals from asking for the professional coaching they desire is budget constraints. With companies no longer approving bonuses and raises and performing layoffs, employees who feel like they would like professional coaching—which could reinvigorate their emotional and mental connection in the workplace—may feel that asking for professional development opportunities of any kind is hopeless. It’s important for clinical leadership to understand that high staff turnover is more costly than investing in their current employees. Employee disengagement can place financial strain on healthcare organizations with higher costs for recruitment, training, and retention. Engaged employees are more likely to stay in their positions longer, saving the organization money it would have spent replacing an unhappy worker. One of the most important metrics to quantify return on investment (ROI) on leadership development coaching is employee engagement.

When employees are engaged and connected with their work, they’re more productive. Increased productivity for all employees, regardless of where they fall in the organizational chart, directly benefits a company’s bottom line. Professional coaching is just one piece of the employee engagement puzzle, but it’s an important consideration for individuals who look for an organization that provides growth and development opportunities. Internal employee engagement surveys are an important step in determining the ROI on leadership development coaching. To get a baseline understanding of how this specific investment in your employees has affected engagement, an internal survey can provide insights into improved performance, satisfaction, and overall team productivity.

Baldwin and Turman, leadership coaches at BSM Consulting (a division of VMG Health), reminded listeners that coaching isn’t just about career growth; it’s about helping individuals recognize the choices they’re making and empowering them to take control of their professional and personal lives. The coaching process often reveals how workplace issues bleed into life challenges, and vice versa. By addressing both, coaches help individuals achieve true transformation.

Leadership development coaching offers an important pathway for re-engaging healthcare employees and fostering a more connected, motivated, and productive workforce. It’s an investment that benefits both the individual and the organization as a whole. If you’re looking to provide leadership coaching to your employees, Coachify Over Coffee offers valuable insights and actionable strategies. Apply a new approach to your leadership with the help of Laura Baldwin and Savory Turman, two certified coaches dedicated to sharing their expertise with listeners like you.

September 12, 2024

Written by Christa Shephard

As artificial intelligence (AI) surges forward as a useful tool in all sectors, its transformative impact is especially noteworthy in healthcare. Hospital management has undergone an overhaul with the implementation of AI-powered solutions, which automates repetitive tasks like scheduling, billing, and record-keeping to reduce administrative burden and prevent errors. While AI might seem like magic, its impact on hospital management is grounded in data-driven algorithms and practical applications that enhance efficiency and decision-making.

AI-powered tools are helping hospitals maintain compliance by improving billing and coding accuracy, but they’re also doing the heavy lifting when it comes to decision-making. These tools analyze vast amounts of data in seconds to provide evidence-based recommendations and identify patterns that might not be immediately apparent to clinicians. Through pattern recognition and predictive analytics, AI-driven solutions identify compliance risks and anomalies in billing and coding, helping hospitals stay compliant with regulations and avoid costly errors.

Issues with regulatory compliance can significantly impact hospital revenue and patient outcomes. Non-compliance with healthcare regulations, such as improper billing or coding errors, can lead to financial penalties, reduced reimbursements, and even legal actions. All of these consequences directly impact a hospital’s bottom line. Beyond financial losses, these compliance lapses erode trust with patients and payers, leading to reputational damage and a decline in patient volume. Regulatory issues often correlate with lapses in patient care standards, potentially compromising patient safety and outcomes. Ensuring strict adherence to regulations is essential for maintaining financial stability and for upholding the quality of care that patients receive.

These challenges are often the result of human error, which has been somewhat inevitable up until the implementation of AI-driven solutions in hospitals. With new software solutions designed to automate repetitive tasks, hospitals can take a proactive approach to mitigating compliance and audit risk.

AI-powered tools not only boost efficiency by streamlining processes and reducing the manual workload, but they also help save hospitals significant amounts of money. Automating routine tasks like scheduling, billing, and administrative duties allows hospital staff to focus on higher-value activities, improving both operational flow and patient care. By eliminating the need for manual interventions, AI-driven systems reduce the risk of human error, leading to fewer costly mistakes and enhanced overall productivity, ensuring day-to-day operations run more smoothly.

In addition to driving efficiency, AI enhances accuracy in billing and compliance, which can further reduce financial risk. AI-driven systems quickly analyze large datasets to identify potential discrepancies in billing, ensuring compliance with regulatory standards and avoiding penalties. This level of accuracy minimizes revenue loss from overlooked billing errors. Additionally, AI provides actionable, data-driven insights that enable healthcare providers to optimize their financial performance. These insights improve patient outcomes while identifying cost-saving opportunities, making AI an indispensable tool in maintaining a competitive edge while reducing operational expenses.

VMG Health is proud to offer AI-powered solutions that proactively identify and eliminate compliance risk, alleviate the burden of some manual tasks, and offset their own cost by minimizing costly mistakes. Our Compliance Risk Analyzer (CRA) suite offers cutting-edge solutions designed to safeguard revenue and minimize regulatory exposure. It uses predictive analytics to identify potential areas of compliance and audit risk, empowering hospitals to take a proactive approach in mitigating costly mistakes—as opposed to having to react after those mistakes have been made.

CRA, combined with our coding audit experts, streamlines risk mitigation and creates an action plan for hospital teams, providing the option to fully outsource audit departments. Our tool’s easy implementation and user-friendly interface ensures hospital staff can quickly train and grow comfortable using it.

VMG Health offers two CRA tools to meet hospital management needs: CPT and DRG. Our CPT tool is designed to assess compliance risks associated with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT®) coding, ensuring accuracy and adherence to standards. The DRG tool specializes in managing compliance risks related to Diagnosis-Related Group (DRG) coding, providing a targeted approach for inpatient settings. Each solution offers a specialized solution to enhance compliance and efficiency.

Hospital management is fraught with repetitive tasks, compliance risk, and difficult decision-making. Alleviating these challenges empowers hospitals to enhance their operational efficiency, allow staff to focus on higher-value responsibilities, proactively identify and eliminate compliance risk, and boost their bottom line. AI-powered solutions like CRA pay for themselves when they identify risk areas like undercoding, which can often uncover significant savings.

While AI might seem like magic, its real power lies in the practical, data-driven insights it provides, enhancing hospital management and streamlining operations. Consider AI-powered solutions for your hospital. VMG Health’s Compliance Risk Analyzer suite is tailored to meet your needs. Protect your organization from audit risks, capture every dollar of revenue owed, and ensure compliance with VMG Health’s Compliance Risk Analyzer suite. Contact our Coding Audit & Compliance experts to learn more about our state-of-the-art solutions.

September 11, 2024

Written by Nicole Montanaro, CVA

The following article was published by the American Association of Provider Compensation Professionals (AAPCP).

Following the introduction of the Final Rules by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) at the beginning of 2021, VMG Health has seen a growing number of organizations prioritizing their value-based care (VBC) strategy through the creation of value-based enterprises (VBEs) and/or structuring arrangements in accordance with the safe harbor framework of the Final Rules. These value-based exceptions and safe harbors are intended to advance the transition from volume to value by allowing for more flexibility in structuring compliant arrangements. Since physicians are often the cornerstone of any VBC strategy due to their ability to drive savings and clinical quality, this added flexibility of the Final Rules has prompted many healthcare leaders to revisit and modernize their physician alignment models.

With the unwavering prominence of VBC in the market, there are already numerous alignment strategies where healthcare providers enter into value-based arrangements with physicians to improve clinical quality outcomes, coordination of care among providers and across care settings, and cost efficiencies in exchange for an incentive or bonus payment that is subject to performance metrics. In some cases, healthcare providers like hospitals and health systems are internally creating and self-funding these programs in anticipation of future changes to reimbursement. While in other cases, healthcare providers may already have payer contracts in place where they are eligible for value-based reimbursement and may want to share a portion of the incremental reimbursement and shared savings payments with the physicians who contributed to this achievement.

Regardless of the alignment vehicle, when structuring these arrangements with physicians, it is critical to ensure regulatory compliance, and one of the common themes in the Final Rules is the legitimacy of the performance metrics that will be used to trigger value-based payments. Specifically, there is an emphasis on clinical quality outcomes metrics and clinical evidence or credible medical support for these metrics. Additionally, from a valuation firm’s perspective, the credibility of the metrics is one of the primary value drivers in supporting value-based payments to physicians. The following provides insight on things to consider when selecting performance metrics for value-based arrangements and outcomes-based payment arrangements from a valuation firm’s perspective.

It is important to prioritize the selection of the metrics when structuring new arrangements or dusting off old arrangements. The performance metrics should be aligned with the value-based goals of the arrangement to create a meaningful and impactful program and support regulatory compliance. Additionally, from an FMV perspective, having a substantive set of metrics is a key factor in supporting or justifying value-based payments to physicians. Performing an FMV assessment helps to mitigate compliance risks and supports equitable payment models that reward physicians for their level of contribution toward achieving the value-based goals.

When it comes to determining the FMV of value-based payments to physicians, it is important to note that there is generally more flexibility if the payments can be tied to an external third party (such as effectively being funded by value-based reimbursement from a governmental or commercial payer). However, if the program is self-funded, there is generally more risk from a compliance perspective, so these programs may require more intense consideration of certain attributes of the subject program, such as the specific metrics to be utilized, to bolster support for the value-based payments.

Industry research related to value-based payment models in the market and regulatory guidance has consistently revealed the importance of key, metric-related attributes when structuring value-based payment arrangements with physicians. The following summarizes some of these key factors:

Analyzing the industry research from a valuation perspective, factors such as paying for the achievement of “superior” performance standards (typically consistent with the national top decile) and selecting physician-driven, patient clinical quality outcomes metrics that are supported by credible, medical evidence can help to justify higher value-based payments to physicians.

Total Your Points to See How Your Metrics Score

A = 10 points

B = 5 points

C = 0 points

A. Yes

B. Some

C. No

2. Has management considered the needs of the facility and/or patient population in the selection of the metrics?

A. Yes

B. Some

C. No

3. Are the selected metrics supported by credible, medical evidence for improving quality, efficiency, and patient outcomes?

A. Yes

B. Some

C. No

4. Do the selected metrics overlap with or duplicate any services required under medical staff bylaws and/or other arrangements?

A. No

B. Some

C. Yes

5. Has management established meaningful performance targets for each metric that are difficult to achieve or based on a material improvement from baseline performance (i.e., stretch goals versus maintenance goals)?

A. Yes

B. Some

C. No

6. Is achievement of the selected metrics expected to improve your organization’s performance under value-based arrangements with payers (i.e., will it generate value-based reimbursement for your organization from payers)?

A. Yes

B. Some

C. No

7. Is achievement of the selected metrics expected to generate quantifiable savings on the total cost of care for your organization or for payers?

A. Yes

B. Some

C. No

8. Are the selected metrics outcomes-based (i.e., patient clinical quality outcomes)?

A. Yes

B. Some

C. No

9. Are the selected performance targets for each metric sourced from industry-recognized or national databases (versus internally derived or self-created)?

A. Yes

B. Some

C. No

10. Are the maximum performance targets for each metric consistent with or better than what is considered “superior” level of performance (often consistent with national top decile)?

A. Yes

B. Some

C. No

This article is not intended to be, nor should it be used as, a substitute for legal, valuation, or regulatory advice.

85 Fed. Reg. 77492 (Dec. 2, 2020) (CMS Final Rule); 85 Fed. Reg. 77684 (Dec. 2, 2020) (OIG Final Rule).

September 5, 2024

Written by Ash Midyett, CFA; William Teague, CFA, CVA

After a multi-year drought, the healthcare services industry has helped lead the way in re-opening the initial public offerings (IPO) market, contributing half of the top 10 largest IPOs of the year. In July alone, Ardent Healthcare (ARDT) and Concentra (CON) filed back-to-back IPOs, raising $192 million and $529 million respectively. Ardent Healthcare marks the first traditional health system to IPO in decades, and in this article, we will discuss the company’s performance and offering compared to that of its public peers.

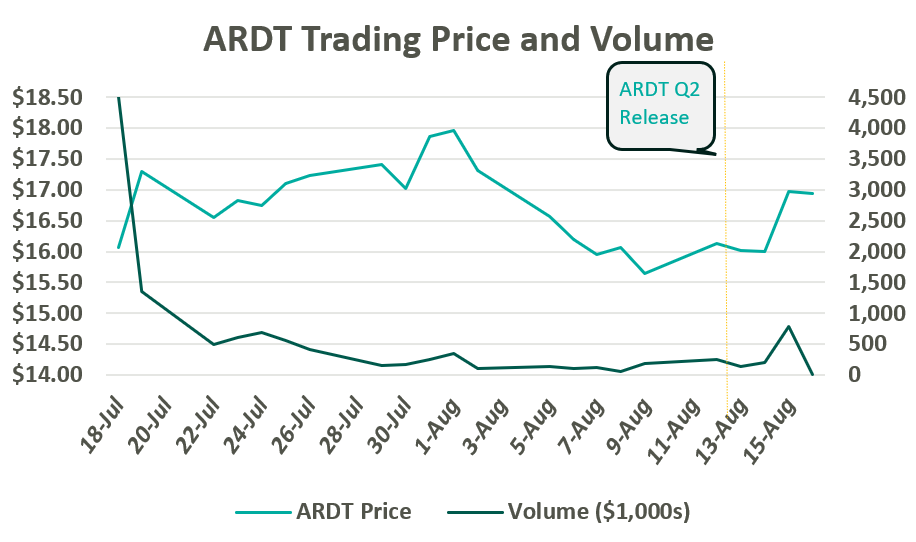

On July 19, Ardent Healthcare listed 12 million common shares on the New York Stock Exchange at $16 per share. After accounting for options granted to underwriters, the proceeds generated $209 million, which is expected to be allocated towards debt repayment and future acquisitions. The IPO marks a notable downshift from their initial price target of $20-$22 per share. Since trading, ARDT moved up toward a peak close of $17.97 before returning to $16.00 per share following a global market sell-off in the first week of August. Following Ardent Healthcare’s Q2 Earnings release on August 14, their shares jumped 6% to $16.97.

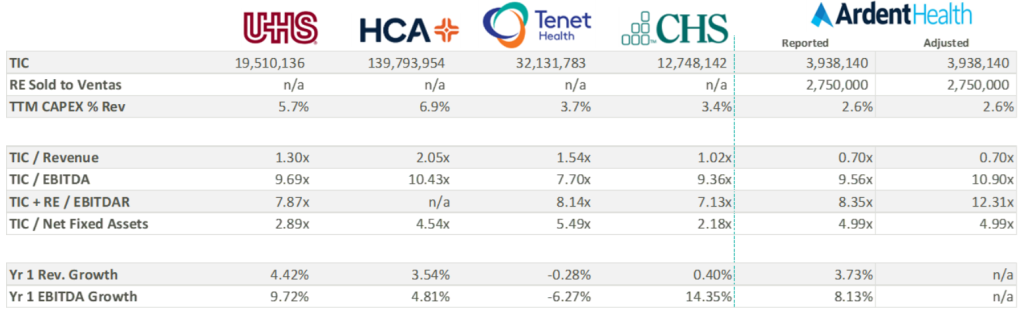

Since the company’s founding in 2001, Ardent Healthcare has grown into the fourth largest, for-profit hospital operator and healthcare services provider in the United States. The company currently operates 30 acute care hospitals and over 200 sites of care. Its market footprint spans eight mid-sized, urban markets across six states: Texas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, New Jersey, Idaho, and Kansas.1,2

Ardent Healthcare is listed as a “Controlled” company, meaning control and shareholder rights are concentrated with the company’s private equity sponsor, EGI-AM Investments, L.L.C. EGI-AM Investments acquired Ardent Healthcare in July 2015 and has since supported an aggressive business development strategy characterized by scale and leverage. From 2015 to 2018, Ardent Healthcare nearly tripled its operating revenue through the acquisition of 16 hospitals and 95 other sites of care while generating margins between 6% and 10%. While Ardent Healthcare aggressively expanded its footprint, the company simultaneously divested most of its real estate to an affiliated REIT, Ventas, Inc.

Ardent Healthcare’s inorganic growth is primarily attributable to three large joint ventures, which exemplify the company’s established business development strategy. In March 2017, Ardent Healthcare acquired five hospitals from LHP Hospital Group, Inc. and, in turn, established a joint venture with the University of Kansas Health System. The acquisition was quickly followed by the acquisition of St. Francis Health Center in Topeka, KS in May 2017. Within a year, Ardent Healthcare made its largest acquisition to date and acquired a majority stake in 10 hospitals and 39 clinics from East Texas Medical Center Regional Healthcare System, a subsidiary of the University of Texas Health System during March 2018.

All three acquisitions adhere to Ardent Heathcare’s purported strategy of founding joint ventures with established, not-for-profit and academic health systems located within growing, mid-sized markets.

During its expansion period, the Company sold off most of its real estate to Ventas, Inc. and other affiliated REITs while paying out significant distributions to shareholders. In July 2015, Ardent sold the real estate for 10 acute-care hospitals to Ventas for $1.75 billion, shortly followed by a special distribution of $500 million to shareholders. Between 2018 and 2020, Ardent Healthcare sold off the real estate for 14 skilled nursing facilities and the three more acute-care hospitals for a total of $1 billion. Meanwhile, Ardent Healthcare paid out an additional $950 million in special dividends.

Real estate lease backs are nothing new to the healthcare services industry, but Ardent Healthcare marks the first publicly traded healthcare services company to pursue this strategy at scale. The cash infusion from the sale represents an opportunity to optimize capital structure via debt repayment, reward shareholders, and equip the company with dry powder to pursue future acquisitions. Meanwhile, real estate can trade independently with the oversight of a specialized management team. However, the lease backs also add operational leverage, adding a fixed rental expense to the income statement, similar to fixed interest on a loan.

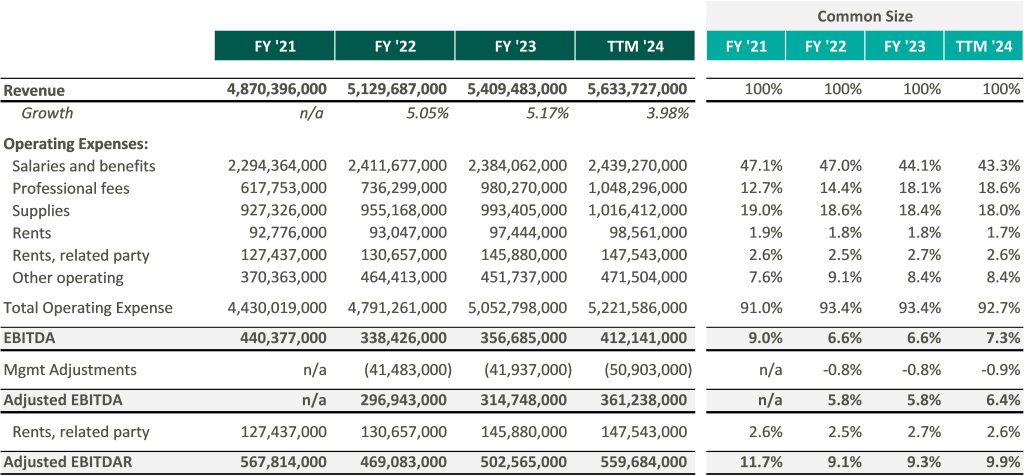

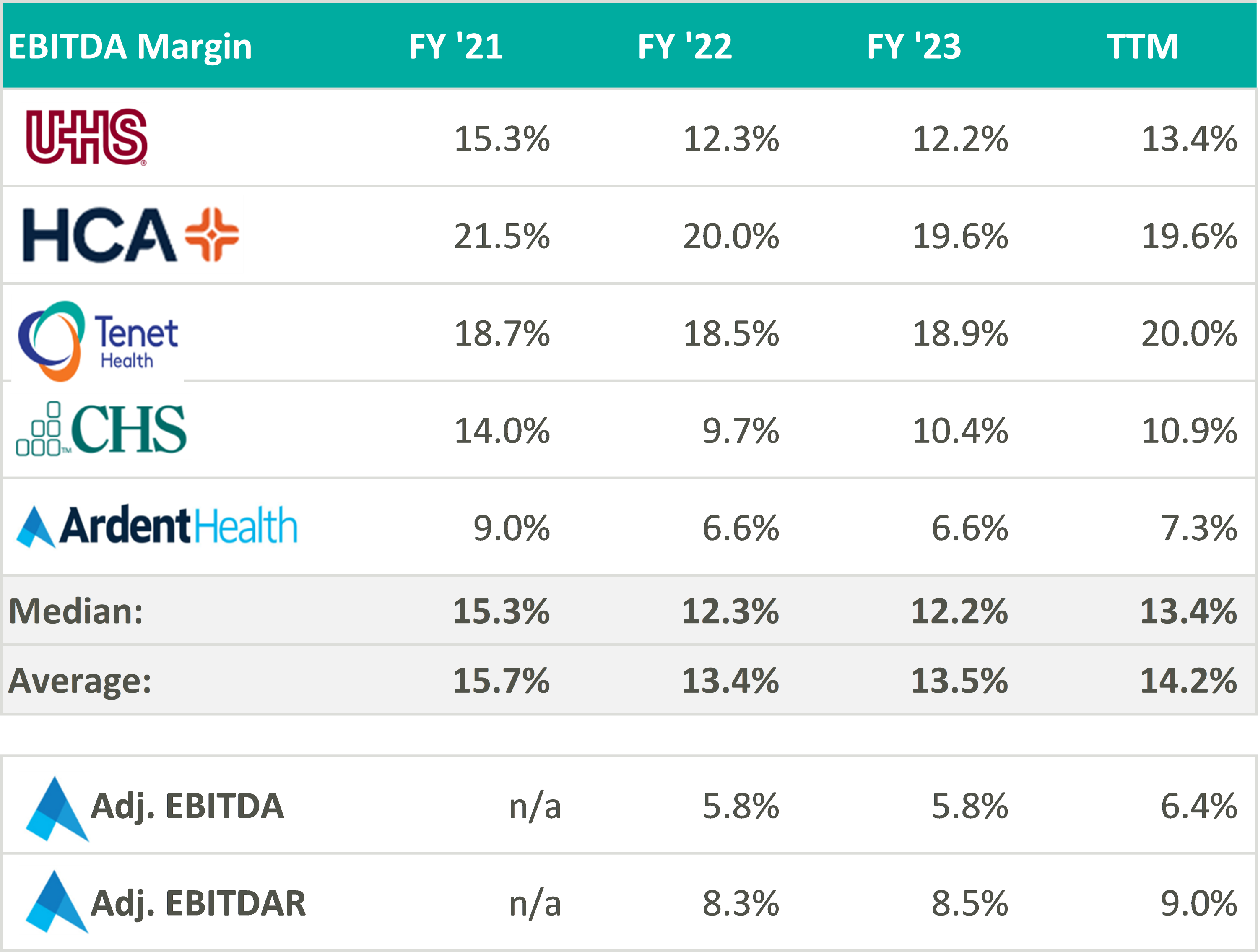

In recent marketing materials, Ardent Healthcare has advocated for analysts and investors to consider their valuation in relation to its EBITDAR multiple rather than EBITDA because of its unique expense structure. However, after accounting for rental expenses, Ardent Healthcare’s margins fall below those of its peers thereby increasing free cash flow volatility.3

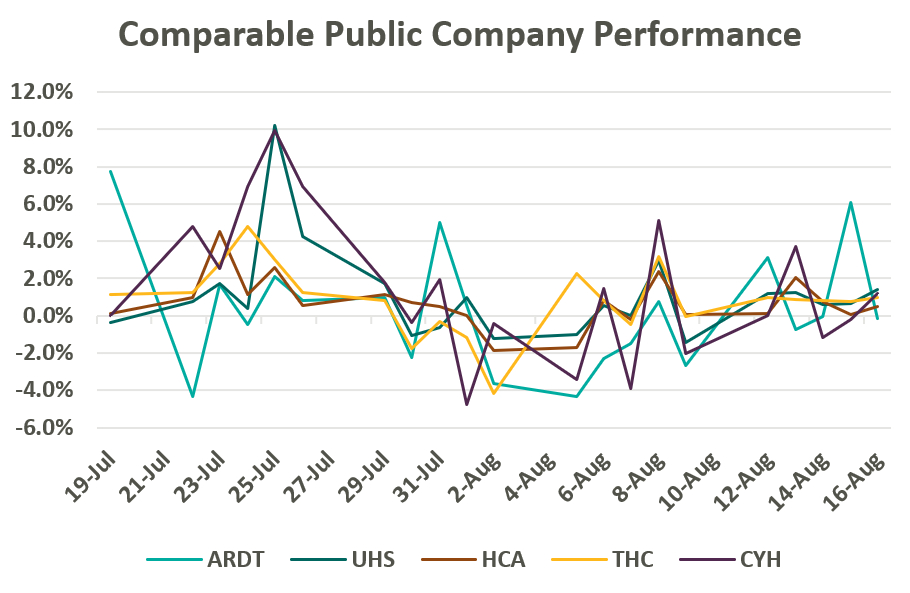

Despite lower margins and a higher-risk balance sheet, Ardent Healthcare’s implied trading multiple remains in line with its peers (or above after management adjustments to EBITDA): United Health Services (UHS), HCA Healthcare Inc. (HCA), Tenet Healthcare Corporation (THC), and Community Health Systems (CYH). As of August 19, Ardent Healthcare’s market capital roughly implies a 9.5x reported EBITDA multiple compared to the peer group median of 9.3x reported EBITDA.4

Over the three most recent fiscal years, Ardent Healthcare has reported capital expenditures well below those of its peers. All things equal, a lower capital expenditure increases cash flow to equity and thereby increases valuation—not to mention bolstering distributable free cash flow for shareholders. While some of the discrepancy in capital expenditure may be attributable to Ardent Healthcare’s asset light balance sheet, Ardent Healthcare’s lease agreement with Ventas stipulates a triple net lease obligation. It is possible that the company may be beholden to higher capital investment in the coming years, decreasing cash flow and shareholder value.

Perhaps more important to value is the company’s growth expectations, which currently appear elevated compared to peers. As seen in the table above, analysts are anticipating an 8% increase in EBITDA over the coming year compared to the peer group median of 5.5%. Three-year growth expectations considerably outpace peers as the company gains scale and increases revenue.

Ardent Healthcare’s growth strategy, outlined in its recent S-1 filing, will be key to growing market share, scale, and margin to best compete and grow into its current valuation. Specifically, Ardent Healthcare’s inorganic growth strategy remains focused on expanding its portfolio of joint ventures and has identified an addressable market of nearly 350 mid-sized, urban communities. Ardent Healthcare also intends to embolden its ACO participation and value-based care programs while accelerating their ambulatory and physician alignment initiatives (with eight new ambulatory surgery centers added in Q2 alone). Coming off a strong quarter, Ardent Healthcare certainly has ample opportunity to expand its stated 3% market share and continue providing high-quality care to its patients. VMG Health looks forward to following the company’s performance in the coming quarters.

August 28, 2024

Written by Dylan Alexander, CVA and Karly Bruss

The ambulatory surgery center (ASC) industry continues to experience steady, reliable growth, and remains a highly profitable segment within the healthcare provider sector. This growth has attracted significant attention from investors, captivated by the sector’s promising returns. The ASC industry’s success is underpinned by several key factors: an increase in demand for outpatient procedures, enhanced operational efficiency, technological advancements, favorable regulatory changes, elevated patient satisfaction, and, in some cases, favorable relationships with commercial payers. However, the success of ASCs has introduced a unique challenge: the difficulty of attracting and securing new physician investors.

Successful and stable ASCs typically have high profit margins and generate substantial returns to their investors. While health systems, management companies, and other corporate investors are common in ASCs, the most important class of investors in an ASC are its surgeon utilizers. For physicians to be investors, they are required to conduct a certain percentage of their surgical case volume at the ASC. In addition, most ASC operating agreements have redemption provisions requiring the sale of ownership to be valued at stated multiple of profitability or at fair market value (FMV) when physicians are not meeting case volume requirements, retiring, or exiting the marketplace.

As exiting physicians sell off their ownership, ASCs seek out new surgeon investors to buy in, provide care, and maintain a strong base of physician equity partners to retain case volume and protect or increase profitability. ASC operating agreements typically have buy-in provisions at the same multiple of profitability or at FMV mirroring the redemption provisions. Therein lies the challenge of attracting new investor or utilizer surgeons into the ASC depending on the life cycle of the ASC. New physician investors may not have the ability or the desire to pay the price required to have an ownership interest in the ASC that is on par with legacy investors. Potential new physician investors may be relatively new to their practice, have large debt burdens from medical school, young family considerations, or considering alternative investments in the financial marketplace.

The ASC life cycle, though similar to other businesses, is distinctive due to its cyclical nature and dependence on surgeon volume and investment.

In the start-up phase, significant investments are made to secure a facility, purchase necessary medical equipment, recruit staff, acquire the appropriate licensure, and fund initial working capital. Because the overall value of an ASC is typically at its lowest during the start-up phase, potential physician investors may be unwilling to accept the financial risk of a new venture that may not be cash-flow positive in the immediate future. However, the returns on their investments for the initial physician investors can be the highest for a successful ASC. During this phase, physician shareholders are usually unlikely to exit, and the ASC’s focus is syndicating the initial physician ownership base for what is expected to be a highly successful ASC given the desired surgical specialty mix.

In the growth phase, the ASC establishes its relationship with physician utilizers (both investor and not), managing surgical block times, developing its patient base, refining payer contracting, and reaching operational efficiency through case volume adequacy given the size and specialty mix of the ASC. During this phase, ASCs are often profitable but still not ramped to optimal and full capacity levels. The growth phase can represent an ideal time for new physicians to consider buying in, as the purchase price is often less and the potential for higher returns still exists. Physician investors exiting the ASC can also get strong returns on their initial investment from the start-up phase.

ASCs have achieved financial stability and operational efficiency in the maturity stage. Mature ASCs typically generate significant cash flow, leading to high valuations. As discussed, high valuations can be a barrier to entry for new physician investors. In a sense, ASCs can be a victim of their own financial and operational success. Though returns are stable, mature ASCs have usually reached their maximum capacity or are nearing capacity. Additional capital investment in space and equipment could be required to maintain the ASC’s current level of profitability. Most importantly, the ASC must manage the retirement and exit of certain key physician investors by replacing them with case volume from newer physicians. If new physicians successfully replace exiting physicians in ownership, the maturity stage can be maintained for the foreseeable future. Valuations at this stage are typically high and consistent over time with equitable returns to both exiting and buying surgeons. It is at the end of this stage that many ASCs encounter the challenges discussed previously. If an ASC is unable to attract new physician investors due to market factors, a shortage of physicians, or pricing constraints associated with success, it may face declining profitability and overall value.

The exit phase, or decline phase, is characterized by shareholder physician attrition outpacing new physician investment. The value of an ASC declines as the departing shareholders no longer contribute case volume, and finding physicians to buy in remains a challenge. At this point, it is common to see a few physicians or the corporate partner increasing ownership due to shareholder redemptions with no new physicians to invest.

ASCs remain one of the more attractive investments in the healthcare space because of their proven resiliency when managed appropriately. Long-standing, successful ASCs may have been through this life cycle several times. At the decline phase, the value of the ASC will likely be at one of its lower points, creating an attractive purchase price for interest by new surgeon investors. If ownership is re-syndicated to align with growth and key physicians, the ASC then starts at the growth phase and moves to maturity with its new base of physician owners.

The increasing demand for outpatient procedures and the opportunity for substantial returns make ASCs a desirable option for potential physician investors. Physician alignment through investment is critical to the success of any ASC and is the key factor in the life cycle of the business. When determining values for physician investment and redemption, it is essential to consider the current and expected future operations.

The valuation of the ASC should be as accurate and thoughtful as possible—not only for the relationship between physician buy-ins and redemptions to maintain the operations of the ASC, but for regulatory requirements as well. Often, ASCs engage an independent and unbiased third party to conduct a fair market value analysis pursuant to any ownership transactions. VMG Health, with its experienced team, provides expert knowledge and data-driven analyses to support parties in ASC transactions. Our expertise in the ASC marketplace enables stakeholders to navigate the challenges and opportunities associated with ASC investments as they move through their life cycle effectively.

August 21, 2024

Written by Frank Cohen

In recent years, key Supreme Court rulings have significantly altered the field of administrative law. One crucial decision involves the Court’s June 28, 2024 overturning of the Chevron deference, a long-standing doctrine that has governed how courts engage with agency interpretations of statutes. This change may have far-reaching implications for various administrative processes, including Medicare audit hearings. This article explores the impact of rejecting Chevron deference on administrative law judge (ALJ) hearings, particularly those related to Medicare overpayment estimates based on statistical sampling.

The Chevron deference doctrine was established in the 1984 Supreme Court case Chevron U.S.A., Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. This doctrine specifies that, when a statute is ambiguous, courts should defer to an agency’s interpretation of it as long as the interpretation is reasonable. The rationale behind this doctrine is that agencies are presumed to possess specialized expertise, making them better equipped to handle technical details than courts. Chevron deference was meant to respect the separation of powers by recognizing the executive branch’s role in enforcing laws, ensuring courts do not overstep their boundaries by second-guessing agency expertise.

Chapter 8 of the Medicare Program Integrity Manual (MPIM) offers only a broad overview of using inferential statistics and conducting statistical sampling to estimate overpayments (SSOE) in Medicare audits. These guidelines have traditionally been highly regarded in ALJ hearings and often carry more weight than the results, conclusions, and opinions presented by statisticians representing healthcare providers. This preference was based on the premise that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) possessed the expertise to interpret and apply complex statistical methods effectively. This is the definition of Chevron deference.

MPIM’s Chapter 8 contains only nine pages regarding the statistical models and processes involved in the SSOE analysis. However, an extensive body of literature exists on this subject in various formats and sources. When ALJs rely on the factors in these nine pages, it hampers the provider’s ability to mount a compelling defense that challenges the auditor’s methods using widely accepted standards within the statistical community. On the other hand, this deference is meant to ensure audit hearings are grounded in established regulatory interpretations, providing a consistent framework for decision-making. It does not preclude providers from challenging the auditor’s methods. Instead, it ensures any defense is presented within the context of recognized standards, maintaining the integrity and fairness of the process.

The Supreme Court’s overturning of Chevron deference represents a significant change in administrative law and, consequently, ALJ hearings. The decision reflects concerns about the separation of powers and the judiciary’s role in interpreting the law. Critics of Chevron deference argue that it gave agencies too much power to define their own authority, thereby weakening judicial oversight and denying healthcare providers’ due process. Supporters of Chevron deference argue that it allows agencies with specialized expertise to interpret complex and technical statutes, ensuring more informed and consistent regulatory decisions while promoting efficiency and stability in the regulatory process.

It is reasonable to expect that this ruling will have a significant impact on the financial damages incurred by healthcare providers due to extrapolated overpayment findings. However, the ruling could create a more complex and uncertain regulatory environment, making it harder to predict and comply with regulations. The impact can affect various areas of the audit process.

With Chevron deference no longer in play, ALJs will hopefully scrutinize CMS guidelines more critically, including Chapter 8 of the MPIM. This means the methodologies and assumptions used by CMS for statistical sampling and overpayment estimation could be subjected to more rigorous judicial review during Medicare audit hearings. ALJs will no longer automatically favor CMS’ interpretations of Chapter 8 but will evaluate them alongside expert testimony from statisticians representing providers. However, this also means that judicial rulings may be inconsistent without agency interpretations of ambiguous statutes. Different courts may interpret regulations differently, leading to inconsistent enforcement. This inconsistency could create a patchwork of regulatory requirements across different jurisdictions, complicating compliance efforts for healthcare providers operating in multiple areas.

The recent overturning of Chevron deference marks a significant shift in the landscape of expert testimony in ALJ hearings. Providers may potentially expect a fairer and more balanced evaluation of the analysis and methodologies presented by their statisticians. As a result, there is an increased incentive for providers to seek highly qualified experts who can effectively challenge CMS’ statistical approaches and provide alternative interpretations based on robust statistical principles. This shift promotes a more equitable playing field and encourages the use of expertise to strengthen the quality of evidence presented in ALJ hearings.

The CMS guidelines are not always beneficial for providers regarding Medicare audit disputes. By more mindfully following these guidelines, providers will likely have better results. ALJs may potentially consider the evidence from both parties more fairly. This could lead to lower overpayment estimates or the dismissal of the extrapolated overpayment findings. Now more than ever, providers need to be more strategic, focusing on the quality and persuasiveness of their experts’ analyses and testimonies.

The Supreme Court’s overturning of Chevron deference marks a significant paradigm shift in the power dynamics between administrative agencies and the judiciary. In the context of Medicare audit hearings, this shift implies that ALJs are no longer bound to automatically adhere to the guidelines set forth by CMS, as outlined in Chapter 8 of the MPIM. Instead, ALJs are now expected to assess all evidence presented, including expert testimony from healthcare providers, potentially leading to more favorable rulings for the providers. As the legal framework undergoes transformation, healthcare providers must proactively adapt by employing expert analyses and presenting counterarguments against agency methodologies to ensure accurate audit outcomes.

August 14, 2024

Written by Matthew McKenzie, CVA; Jay Ostrom, CVA

The following article was published by the American Association of Provider Compensation Professionals (AAPCP).

Due to the complexities of the modern healthcare environment, there is a broad range of compensation structures in provider services agreements to facilitate ease of administration while maintaining regulatory compliance. While common compensation structures such as a compensation-per-Work Relative Value Unit (wRVU) model can be effective in reimbursing providers for the value of professional services, independent physicians and physician practices are sometimes compensated based on a per-service rate for each individual unit of service they provide, rather than a rate per wRVU. To ensure arrangements utilizing this structure are commercially reasonable and consistent with fair market value (FMV), hospital administrators should understand the value drivers of the rates that can be paid for per-service fees. In this article, we will discuss potential benefits and drawbacks of the per-service fee structure, as well as explore several key considerations when setting rates and capturing appropriate expenses.

Similar to the compensation-per-wRVU model, a per-service fee structure determines the total compensation payable to a provider based on the unit volume of services rendered. However, rather than the unit of compensated service being the wRVU, the compensation unit is tied to the volume of each CPT code rendered or a broader service category.

For example, consider a scenario in which a radiology group provides a hospital with X-ray, MRI, CT scan, and ultrasound interpretation services. Rather than receiving fixed compensation-per-wRVU based on the wRVUs associated with each interpretation, each interpretation category (X-ray, MRI, CT scan, and ultrasound in our example) would have its own unique compensation rate.

In general, the primary sources of value for these arrangements are the professional services rendered by the provider. While there are various ways to quantify the value of providers’ professional services, the two most common methods are described below.

In determining the compensation for professional services per unit of service, one consideration is the clinical provider time required to provide that unit. In general, the more provider time required to perform a certain service, the greater the value of the service rendered. As such, a reasonable method of determining the value of the professional component of compensation for a unit of service would be to assess the average time spent by the clinical provider on said unit.

Professional reimbursement rates can also be a useful measure of the value of professional compensation on a per-service basis. In many cases, hospital administration will have data indicating the average professional reimbursement rates realized per unit of service performed. When this data is unavailable, a good starting point for assessing reimbursement for professional services is the Medicare reimbursement for the wRVU associated with the relevant Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes as reported by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). This professional reimbursement should be based on the applicable CPT code or bundle of CPT codes that the provider will use for each unit of service. The reimbursement may quantify professional services more accurately than a solely time-based approach, as the Medicare reimbursement also considers the specific skill, training, and acuity of the subject service.

While Medicare reimbursement is a good starting point in understanding professional reimbursement for provider services, actual revenue generated for said services is unlikely to fall directly in line with Medicare reimbursement. Rather, professional reimbursement for a given service is a function of the payer mix of the subject services. While the specific payer mix of an arrangement needs to be understood to accurately determine the professional revenues generated per unit of services provided, there are a few general rules that can inform the directionality of the adjustment.

For most professional services, commercial reimbursement is typically greater than Medicare reimbursement. As commercial payers often reimburse at higher rates than Medicare, a service line payer mix primarily comprised of commercial payers will usually generate more revenue per unit than a service line comprised of fewer commercial payers. The higher revenue associated with the subject services may justify an upward adjustment in the per-service rates payable to the provider.

Medicaid and uninsured payers typically reimburse at rates lower than Medicare. As Medicaid and uninsured payers reimburse at lower rates than Medicare, a service line payer mix primarily composed of Medicaid and uninsured payers will generate less revenue per unit than a service line composed of fewer Medicaid and uninsured payers. In this scenario, the relatively lower revenue associated with the subject services may require a downward adjustment in the per-service rates payable to the provider.

While payer mix does have an impact on the revenue generated for the services provided, the actual services rendered by the provider are not dependent on the payer mix and, in many scenarios, the provider has little to no control over the payer mix. These dynamics should be considered when utilizing mix data to determine the per-service compensation payable to a provider.

Another method of quantifying the value of the professional compensation applicable to a unit of services provided is market survey data. For example, compensation-per-wRVU data for a wide array of provider specialties is readily available through healthcare compensation survey reports. This data may be applied to the average wRVUs that the provider would generate per unit of service to determine an estimate of the market professional compensation payable per unit.

As opposed to the use of actual professional reimbursement to determine professional compensation rates (which consider the actual funds available to compensate the providers), the use of market-based compensation data can provide an indication of value that reflects actual compensation rates paid in the market for similar services. However, the use of market survey data is limited by the reliability of the reported survey data and the data’s applicability to the subject services. It is important that organizations understand the survey data they are utilizing and how the specific details of an arrangement may impact the applicability of market survey data.

As previously mentioned, one benefit to the per-service compensation model is the ability to include provisions for certain variable overhead expenses incurred by the provider per unit of service. There are several ways to determine the value of these variable expenses.

One way to determine a provision for additional variable expenses is by assessing the actual incremental variable expense incurred by the provider. Should the provision for non-professional variable cost per unit be based on the actual costs incurred by the provider, the reimbursement for variable expenses is effectively a direct pass-through from the provider to the contracting entity. While this method reduces the risk of over- or underpayment for non-professional services, it is important that the contracting entity ensures the following assumptions are true:

In the absence of actual incremental expense data, Medicare reimbursement associated with practice expense (PE) RVUs can also be useful in determining a provision for overhead associated with a unit of services provided. Specifically, reimbursement associated with the PE RVUs for the CPT code, or bundle of CPT codes, for a given service indicates reimbursement for non-professional expenses incurred, consistent with guidelines from CMS.

When utilizing PE RVU data, it is important to recognize the site of services in which the subject services are provided. CMS illustrates PE RVU data for services provided in a facility setting (e.g., hospitals, ASCs, SNFs, etc.) and a non-facility setting (e.g., outpatient clinics, urgent care centers, etc.). PE reimbursement is higher for services provided in the non-facility setting because the provider is assumed to bear the responsibility of all overhead (i.e., space, equipment, etc.) while the facility is assumed to bear these costs in the facility setting. Therefore, identifying the correct site of service is imperative for accurate application of this method.

Another consideration in deciding the payment rate for each service provided by a provider is who has the authority to bill and receive payment for the services provided. If the provider is unable to bill patients for any of the services provided, compensating the provider with a fully loaded rate, inclusive of provisions for professional and any technical services provided, may be appropriate.

Should the provider bill and collect for services rendered under an arrangement and retain those collections, the collections earned by the provider should offset the fully loaded rate that would otherwise be payable to the provider. For example, if the provider’s collections per unit were sufficient to cover their expenses incurred to provide the service, it may not be appropriate to provide any additional compensation to the provider. However, a payment subsidizing provider services in addition to the collections retained by the provider may be appropriate if the provider’s collections per unit are not enough to cover their expenses (e.g., if the provider has expenses of $30 per unit but can collect only $20 per unit, a payment covering this disparity may be reasonable). Because reasonable payment to providers who can bill and collect is dependent on their actual collections per unit (which varies dependent on the payer of the service), organizations should be diligent when determining rates per service in these scenarios.

In addition to the actual collections generated by the provider in the provision of the services, the cost of billing and collecting should be considered when determining a reasonable per-service compensation rate. For example, professional reimbursement from payers typically includes a provision for the costs associated with billing and collecting. However, market provider compensation data does not typically include a provision for billing and collection costs. As such, make appropriate adjustments depending on the valuation method used and the billing and collection responsibilities of the subject arrangement.

When a service is requested on an urgent basis, an increase in the compensation payable to a provider may be justified. For example, per-service compensation for services ordered emergently (e.g., STAT cases) could potentially earn more compensation than the same services that do not require an expedited turnaround time to account for the on-call availability of the provider. Typically, additional compensation based on the urgency of a service is only contemplated if the expedited turnaround time is deemed medically necessary.

Per-service compensation structures can be an effective way to compensate providers for services that include additional variable expenses above and beyond the providers’ professional services. However, hospital administrators must understand the value drivers behind per-service compensation rates and the risks associated with the structure to ensure arrangements are commercially reasonable and compliant with healthcare regulations.

August 13, 2024

Written by Savanna Ganyard, CFA; Joshua Miner; Chance Sherer, CVA; and William Teague, CFA, CVA

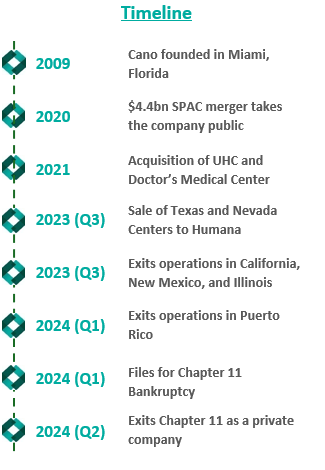

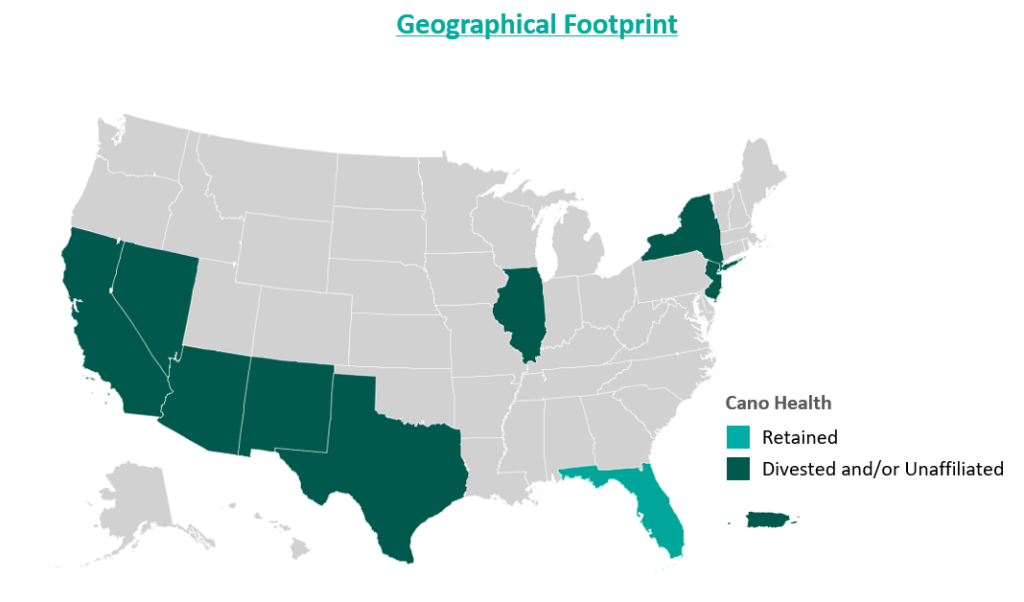

Cano Health, Inc., headquartered in Florida, is a value-based care delivery platform that specializes in primary care for seniors. In February 2024, Cano announced it would enter a reorganization process under Chapter 11 bankruptcy. Less than six months later, on June 28, 2024, the company announced a successful conclusion of its court-supervised restructuring. The company, now private, is looking forward to a brighter future under a more focused strategy.

Founded in 2009, Cano began developing its core business as a value-based provider in Florida. The company employs a capitated care model and places a large focus on preventative care and accessibility. The company’s membership is largely comprised of Medicare Advantage, Medicaid, and ACO REACH. As Cano grew, it added complementary service offerings, such as a care management program, a prescription program, and in-home medical visits. These services were meant to prevent hospital admissions and readmissions, increasing Cano’s revenue while decreasing patient total cost of care in the capitated care model.

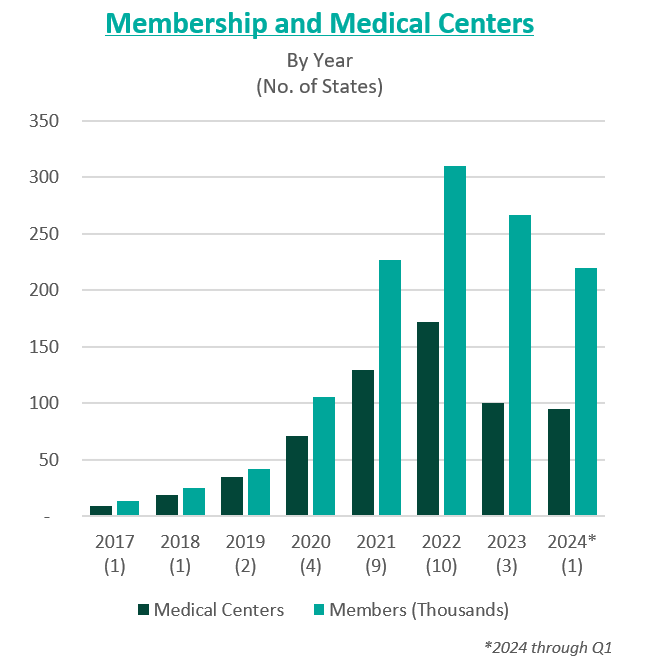

To further drive growth, the company began to pursue an aggressive policy of expansion through de novo development, acquisitions, and affiliations. The company grew from two markets and 13,700 members in 2017 to 15 markets and 106,000 members by 2020.

In 2021, the company went public in a $4.4 billion merger with a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) that provided $1 billion in cash proceeds to the company. After going public, Cano continued to fuel growth through acquisitions. In 2021, the company acquired Miami-based University Health Care in a $600 million deal and Doctors Medical Center in a $300 million deal. The company added five states and 121,000 members in 2021, resulting in a total of nine states and 227,000 members. The company continued this growth throughout 2022, ending the year in 10 states and with 310,000 members.

However, in these years of high growth following going public, the anticipated benefits of these acquisitions did not materialize. The company was also affected by industry and regulatory headwinds, including increasing third-party medical costs and a looming Medicare Risk Adjustment Model (V28). On top of these issues, Cano continued to add debt and fell behind on debt repayments. Throughout 2022 and 2023, Cano reported significant losses and an accumulation of $1.2 billion in debt. For context, the company had $1 billion in assets as of December 31, 2023.

In February 2023, Cano entered into a side-car credit agreement with certain lenders. At the end of March 2023, the company’s market capitalization had decreased 90% from its price at the time of its SPAC merger. In April 2023, three board members resigned in protest of company decisions and performance. A couple of months later, the CEO, Marlow Hernandez, stepped down after pressure from shareholders and the former board.

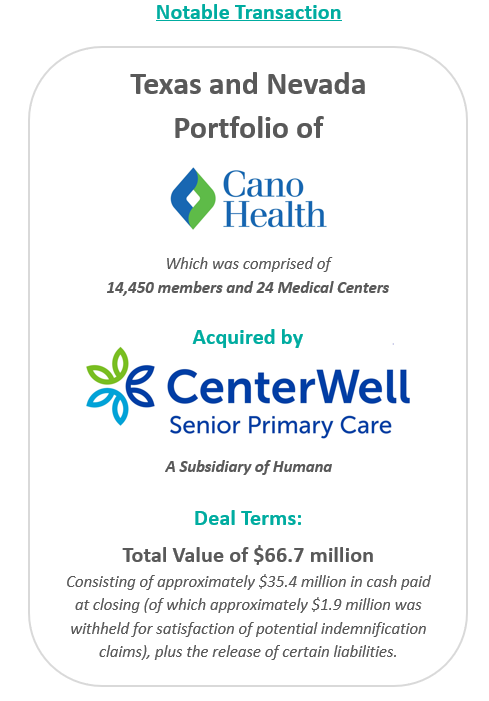

In an attempt improve the company’s performance and cover its liabilities, Cano began to divest its assets. The divestment process began in 2023 prior to the Chapter 11 filing, when the company sold its entire Texas and Nevada portfolio to CenterWell Senior Primary Care, a Humana subsidiary. The net proceeds of the transaction were utilized to pay down debt.

During the second half of 2023, the company also closed medical centers and exited operations in California, New Mexico, and Illinois. These three states represented approximately 5,000 members and 17 medical centers. The company received $19.9 million for the divestiture of certain specialty practices in Florida and assets located in California and Illinois, the net proceeds of which were used as working capital. Cano closed the remaining medical centers in these three states. Finally, Cano successfully exited operations in Puerto Rico at the beginning of 2024.

Despite these transformation efforts, Cano entered into voluntary Chapter 11 proceedings and a Restructuring Support Agreement with most of its lenders in February 2024. The agreement’s primary goal was to reduce debt and position the company for long-term success through cost-cutting measures.

In July 2024, Cano emerged from Chapter 11 as a reorganized private company. The company successfully reduced its debt burden by $1 billion by converting it into equity in the form of common stock and warrants. Additionally, existing investors have contributed an additional $200 million investment to support business operations.

Furthermore, Cano exited its underperforming markets, choosing to focus on its core Florida market. During the bankruptcy process, the court allowed Cano to reject 72 leases in six states. These were sites of offices and medical centers that the company no longer uses.

As established during proceedings, the company’s operational strategy going forward centers around optimizing cost and continuing to evaluate asset performance. To date, Cano is on track to achieve $290 million in cost reductions by the end of 2024. Key drivers of this cost reduction include negotiating with payers, reducing operating costs through decreasing the number of permanent staff, and cutting non-essential spending. In addition, the company is prioritizing Medicare Advantage and ACO Reach lines of business.

Essential to understanding Cano’s emergence from bankruptcy is the amount of divestment the company has undergone. At its peak, Cano operated in nine states and Puerto Rico either directly or through affiliates. To improve operations, the company terminated most of its affiliate partnerships and began to divest many of its operations. Following the reorganization process, the company only operates in Florida. Prior to bankruptcy, Cano had 143 locations in Florida, now reduced to 83 locations.

Cano’s largest asset sale was its centers in Texas and Nevada to CenterWell in a deal worth $66.7 million. At closing, the centers covered 14,450 members and 24 medical centers. These figures imply a multiple of $4,600 per member.

In December 2023, the company commenced a sale process for its ACO Reach line of business. The company has engaged with several bidders, but the transaction has not yet materialized. Cano’s ACO Reach business, which comprises 93,300 members, is projected to achieve $32 million in underwriting margin and $11 million in adjusted EBITDA from August to December 2024. The company also continues to explore sale opportunities related to its Medicaid line of business, which is expected to represent 36,200 members in 2024.

Cano’s financial projections estimate $2.9 billion in revenue and 233,000 members during fiscal year (FY) 2025, growing to $3 billion and 239,000 members by FY 2028. During the same period, the company’s adjusted EBITDA is projected at $125 million, growing to $199 million.

Post-reorganization, the estimated value of Cano at the enterprise level was between $580 million and $720 million. The valuation reflects implied Year 1 (2025) multiples at the midpoint of 5.2x adjusted EBITDA and approximately $2,800 per member.

In June 2024, Cano successfully emerged from bankruptcy as a private company with an improved capital structure and more focused operations. The reduced debt burden, coupled with a $200 million injection of capital, has relieved some pressure on the company as it moves forward. Cano has already made significant progress towards its FY 2024 cost reduction goal, achieving $270 million in cost savings and productivity improvements through the first half of the year. Currently, Cano is focused on its Florida operations but has not ruled out a more prudent expansion in late 2025 or 2026 if it continues to meet its financial goals.

Cano Health, Inc. (n.d.). Press releases, public filings, and investor presentations. Retrieved from www.canohealth.com.

Cano Health. (2023, July 18). Cano Health announces successful emergence from Chapter 11. PR Newswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/cano-health-announces-successful-emergence-from-chapter-11-302186063.html

Cano Health. (2023, June 7). Cano Health announces agreement with unsecured creditors committee and court approval of disclosure statement for its reorganization plan. PR Newswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/cano-health-announces-agreement-with-unsecured-creditors-committee-and-court-approval-of-disclosure-statement-for-its-reorganization-plan-302152012.html

Cano Health. (2023, March 27). Cano Health enters restructuring support agreement with a significant majority of its lenders to strengthen financial position. PR Newswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/cano-health-enters-restructuring-support-agreement-with-a-significant-majority-of-its-lenders-to-strengthen-financial-position-302052889.html

PR Newswire. (2023, March 28). NYSE suspends trading in Cano Health Inc. (CANO) and commences delisting proceedings. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/nyse-suspends-trading-in-cano-health-inc-cano-and-commences-delisting-proceedings-302053778.html

Capital IQ. (n.d.). Investor presentations. Retrieved from Capital IQ website.

Public Information related to Cano Health’s Chapter 11 Plan for Reorganization (Case No. 24–10164). (n.d.). Veritaglobal. Retrieved July 26, 2024, from https://veritaglobal.net/CanoHealth

Klas, M. (2023, July 19). The new Chapter 11 plan for Cano Health aims to exit bankruptcy, cut debt. Miami Herald. https://www.miamiherald.com/news/health-care/article289663459.html

July 18, 2024

Written by Christa Shephard and Maureen Regan, President Elect, NYSSPA

Physician assistants (PAs), soon to known as physician associates and advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), like nurse practitioners (NPs), midwives, CRNAs, and clinical nurse specialists, have been around for decades. The first class of PAs graduated from Duke University in 1967, and in 1965, the first training program for NPs began at the University of Colorado. Since then, for many reasons, both professions have become integral to the quality delivery of healthcare. Although they have different education, training, and scope (PAs trained in medicine and APRNs in an advanced theory of nursing practice model) integrating these professionals into a practice can elevate the patient experience, as their access to the healthcare services they need will increase, and there could be an increase to the bottom-line financials of a practice as a result. Physicians experience greater job satisfaction, as PA and APRN integration helps to alleviate overburdened work schedules, including on-call obligations. Through these benefits, interprofessional integration leads to better patient retention, patient referrals, physician satisfaction, and stronger financial health for practices and health systems.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) certainly plays a role in the practice and reimbursement environment of PAs and APRNs; however, most of the legislative and regulatory environment for practice is determined at the state level. Due to the evolution of each profession and the historical and ongoing shortage of physicians, it’s important for health systems and practices to stay abreast of primary source legislative and regulatory guidance changes regarding scope, documentation, and billing compliance. These factors are also important to ensure an employer is capturing maximum reimbursement for clinical work done by both professions while minimizing their risk of an audit and resulting penalties. Systems and practices must uphold an ongoing, longitudinal review of Medical Staff Bylaws, delineation of privileges, policies, and processes.

CMS recognizes qualified billing providers to render services independently and establishes billing and coding rules for PAs and APRNs to ensure accurate reimbursement and quality care delivery within the Medicare program. These rules outline the scope of practice and reimbursement guidelines for nurse practitioners, physician assistants, certified nurse-midwives, clinical nurse specialists, and certified registered nurse anesthetists who must adhere to specific documentation requirements, including maintaining accurate patient records and submitting claims using appropriate evaluation and management (E/M) codes, like physicians. Additionally, CMS provides guidance on incident-to billing, which allows certain services provided by PAs and APRNs to be billed under a supervising physician’s National Provider Identifier (NPI). Understanding and following CMS billing and coding rules are essential to navigate the complexities of reimbursement and ensure compliance with Medicare regulations.

Because CMS recognizes PAs and APRNs as qualified billing providers but not as physicians, they fall into a separate reimbursement category. When billing under their own NPI, the reimbursement level is less than what it would be if the physician were to bill for the same services. This reimbursement differential does not adversely impact a practice’s bottom line, as remuneration for a PA or APRN is less than a physician and malpractice cost is less.

Physicians may bill for a service that was rendered by a PA or APRN with incident-to services and with split/shared E/M services. VMG Health Managing Director and coding and compliance expert Pam D’Apuzzo says, “There’s two rules, which is where everybody gets themselves into trouble… Those two rules have specific guidelines, both from a documentation and a billing standpoint. The patient type, the service type—everything needs to be adhered to.”

To bill for incident-to and split/shared E/M services, practices must meet specific criteria outlined by Medicare. For incident-to services, the criteria include:

For split/shared E/M services, the criteria include:

These criteria ensure that incident-to and split/shared services are billed appropriately and in compliance with Medicare guidelines. Medicare also dictates that the “substantive portion” of a split or shared visit is more than half of the time a physician or non-physician practitioner spends performing the visit or a “substantive part” of the medical decision making. Practices must continually educate and train all medical staff so that they can successfully adhere to these criteria to avoid billing errors and potential audits. Additionally, practices must continuously monitor to ensure all documentation, billing, and coding processes are followed correctly.

There are tools and services that allow for easier monitoring. “We utilize a tool called Compliance Risk Analyzer, which provides us with statistical insight on coding practices,” D’Apuzzo says. “So, we can data mine ourselves and see what’s happening just based on our views. And this is what the payers, specifically, and the government does as well: They can see the [relative value units] RVUs are for a physician or off the chart, or that a physician has submitted claims for two distinct services at two different locations on the same day.”

This is more common than you might think.

“What’s normally happening in those interactions is that [a physician with two locations] realizes he can’t keep up with all of that patient flow in two places, so they hire a PA and put them at location number two,” D’Apuzzo says. “But now all that billing goes under the physician, so it flags for Medicare.”

With VMG Health’s Compliance Risk Analyzer (CRA), practices can see the same data mining and areas of risk, as the program would flag the RVUs as a potential audit risk. This gives practices the opportunity to self-audit and refine their processes to ensure they are billing and coding appropriately.

VMG Health offers multiple comprehensive services that help health systems and practices implement and follow new procedures and new provider utilization without issue, from honoring existing care models to ensuring provider compensation is fair, compliant, and reasonable.

Cordell Mack, VMG Health Managing Director, says, “We’ve spent a lot of time trying to make sure we get that right, both in terms of the underlying, practice-level agreements as well as the ways in which the compensation model works for both the physicians and the PAs and APRNs.”

In many practices, physicians struggle to handle their case load, which means their busy schedules can prevent them from seeing existing patients and from taking on new patients. Bringing PAs and APRNs into the fold allows physicians to create capacity in their schedules so that they can see new patients.

BSM Consulting (a division of VMG Health) Senior Consultant and subject matter expert Elizabeth Monroe provides an excellent example: “Let’s say we have an orthopedic surgeon who really wants to spend most of their time in surgery. We would want to have that physician in surgery because that’s what their skill set, and licensure permits. With a nurse practitioner or physician assistant providing follow-up, post-operative care, that oftentimes is a much better model. It allows the physician to do the surgical cases only they can do, but it also eases patient access to care.”

This realignment of a physician’s schedule creates an opportunity to provide more patient services, which easily translates to improved patient satisfaction when, without this, they would likely be unable to see their provider when they felt they needed to be seen. While PA and APRN–rendered Medicare services are reimbursed at 85% instead of 100%, our experts say that the 15% differential shouldn’t dissuade practices and health systems from leveraging the integration.

“It’s a very short-sighted approach to just think about, ‘But we could be making 100% instead of 85% if we bill under the doctor,’ because ultimately, we are never able to do that 100% of the time, and it’s a higher risk than it is reward,” says D’Apuzzo.

Additionally, physicians with packed schedules and no other scheduling options may inadvertently rush through appointments to see each patient scheduled for that day. Patients who feel rushed may leave an appointment feeling unheard and like their problem is unresolved. Additionally, when a patient calls and asks for services but can’t be seen for multiple weeks or months, they may never make an appointment and instead turn to another provider for help.

All of this culminates in poor patient retention, which equals a loss of revenue for the practice. Dissatisfied patients will seek treatment elsewhere. However, when practices and health systems embrace an interprofessional team, patients are more likely to be able to schedule appointments when they feel they need to be seen, feel heard in an appointment and even spend less time in the office overall as they are not impacted by OR cases running late, and so on.

“Practices are better able to meet patient demand, and they’re able to really allow physician assistants, nurses… to add a tremendous value for the patients, offering them outstanding care,” Monroe says.

With both patient demand and physician scarcity placing the U.S. health system in crisis, many practices and health systems know they need to integrate PAs and APRNs into their workflows, but they don’t know how. VMG Health offers strategic advisory services that can guide this implementation to ensure practices are educated, compliant, and working within the care model they prefer.

“Our team would want to spend time really trying to identify the underlying care model that practices are trying to, you know, work inside of,” says Mack.

One approach is to assess patient needs and practice capabilities to determine the most effective roles for PAs and APRNS, such as providing primary care, specialty care, or supporting services like telemedicine. Implementing policies and workflows can ensure efficient PA and APRN utilization while maintaining quality and safety standards.

Finally, ongoing training, quality monitoring are essential to ensure their interprofessional integration into the practice or health system effectively meets patient needs, and care provided by PAs and NPs should be included into physician quality and compliance review processes.

“It starts with getting your appropriate documentation in place… [with] supervisory responsibilities and collaborating physician agreements,” says Mack. “It migrates to, ‘What’s the operational agreement among the team?’ and how cases are presented, or how the physician is consulted. So, it’s getting an underlying clinical service agreement among those professionals.”

Optimal PA and APRN utilization shows up in the numbers. When practices increase patient access to care without overburdening physicians, they can accommodate more patients, leading to increased revenue generation. Moreover, because PAs and APRNs often bill at a lower rate than physicians, integrating them efficiently can improve cost-effectiveness, thereby enhancing the overall financial performance of the practice.

“It should realize an ROI, and that ROI should be something more in terms of duties and tasks that other teammates can’t do,” says Mack. “Meaning, it would be unfortunate if a qualified healthcare professional is working at such a capacity whereby duties some of the day-to-day responsibilities should probably be done by teammates working at a higher level of their own individual license.”

Changing existing workflows can be difficult, but the rewards heavily outweigh the risks. Physicians must support interprofessional integration to successfully navigate the transition. Physicians are typically the leaders and decision-makers within medical practices, and their support is essential for implementing any significant changes in workflow or care delivery models, which includes having front office staff, medical assistants, nursing and administrative staff rely and respect the roles of PAs and APRNs. Without physician buy-in, resistance to change may arise, hindering smooth integration and retention.

Physicians play a vital role in collaborating and ensuring a seamless care model is implemented and sustained. By endorsing and supporting the integration of PAs and APRNS, physicians can foster a culture of teamwork and mutual respect within the practice. This collaborative approach promotes a cohesive care team to provide high-quality patient care.

It’s important for physicians to trust and communicate that PAs and NPs are qualified and capable of providing excellent patient care. Allowing them to care for an established patient does not sever the relationship between the physician and the patient; it can actually enhance the patient’s experience and trust in the practice.

“We want patients who have had a long-standing relationship with an MD to be able to see that doctor, and then we want to help the doctor know and understand how to appropriately transfer care over to an APRN within their system or within their practice,” says Monroe. “So, that provider can be still linked to the doctor, and the doctor can still be linked to the patient.”

Furthermore, physician buy-in is essential for maintaining continuity of care and ensuring patients feel confident in receiving treatment from both physicians and PAs and NPs. When physicians actively endorse interprofessional integration and communicate the benefits of team-based care to their patients, it builds trust and acceptance of the practice model. It also fosters billing transparency if a patient gets an EOB with the name of someone other than the physician as the rendering provider.

Physician engagement is critical for the long-term success and sustainability of integration initiatives. When physicians recognize the value that PAs and APRNs bring to the practice, including increased efficiency, expanded access to care, and improved patient outcomes, they are more likely to champion these initiatives and advocate for their continued support and development.

The integration of PAs and APRNs into medical practices and health systems presents a strategic opportunity to optimize patient care delivery and operational efficiency. By expanding access to healthcare services and alleviating the workload of overburdened physicians, integration improves patient and employee satisfaction, and enhances patient retention. However, successful integration requires careful attention to regulatory compliance, billing, and coding practices. VMG Health offers comprehensive billing, coding, and strategy advisory services to support practices in navigating the complexities of integration, ensuring compliance with Medicare regulations, and maximizing reimbursement while minimizing audit risk.

Optimal PA and APRN utilization yields tangible benefits, including increased patient access to care, improved patient satisfaction, and enhanced financial performance. By understanding their education, training, and scope, and by leveraging their unique skill sets, practices can accommodate more patients, reduce wait times, and deliver high-quality care cost effectively. Physician engagement is essential for the successful implementation of integration initiatives, as physicians play a pivotal role in endorsing and supporting interprofessional responsibilities within the care team. Through collaborative leadership and effective communication, physicians can foster a culture of teamwork and mutual respect, driving the long-term success and sustainability of integration efforts.

In summary, strategic integration presents a transformative opportunity for medical practices and health systems to meet evolving patient needs, enhance operational efficiency, and achieve sustainable growth. By partnering with VMG Health for expert guidance and support, practices can navigate the complexities of interprofessional integration with confidence, realizing the full potential of this innovative care delivery model.

Maureen C. Regan, MBA, PA-C, FACHE, DFAAPA, is the President-Elect and Past President of the New York State Society of Physician Assistants (NYSSPA) and a Delegate for the American Academy of Physician Associates (AAPA). She is recognized as a Fellow of the American College of Healthcare Executives (FACHE) and a Distinguished Fellow of the American Academy of Physician Associates (DFAAPA). The views expressed in this article are her opinion and do not represent the opinions of any organization or association she is affiliated with.

American Academy of Physician Associates. (n.d.). History of AAPA. Retrieved from https://www.aapa.org/about/history/

American Medical Association. (2022). AMA president sounds alarm on national physician shortage. Retrieved from https://www.ama-assn.org/press-center/press-releases/ama-president-sounds-alarm-national-physician-shortage

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2023). Advanced practice nonphysician practitioners. Medicare Physician Fee Schedule. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician-fee-schedule/advanced-practice-nonphysician-practitioners

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2023). Advanced Practice Registered Nurses (APRNs) and Physician Assistants (PAs) in the Medicare Program. Retrieved from https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician-fee-schedule/advanced-practice-nonphysician-practitioners

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2023). Incident-to billing. Medicare. https://www.cms.gov/medicare/payment/fee-schedules/physician-fee-schedule/advanced-practice-nonphysician-practitioners

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2023). Medicare Physician Fee Schedule final rule summary for calendar year 2024. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/mm13452-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rule-summary-cy-2024.pdf

Mujica-Mota, M. A., Nguyen, L. H., & Stanley, K. (2017). The use of advance care planning in terminal cancer: A systematic review. Palliative & Supportive Care, 15(4), 495-513. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5594520/

June 11, 2024

Written by Timothy Kent, CVA; Jordan Tussy, CVA; Molly Smith

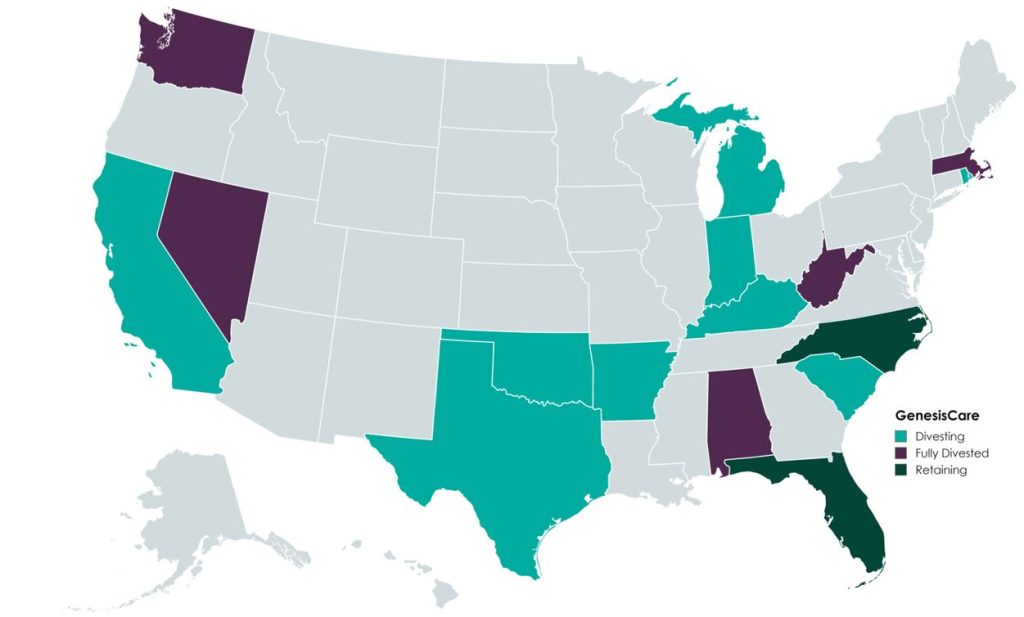

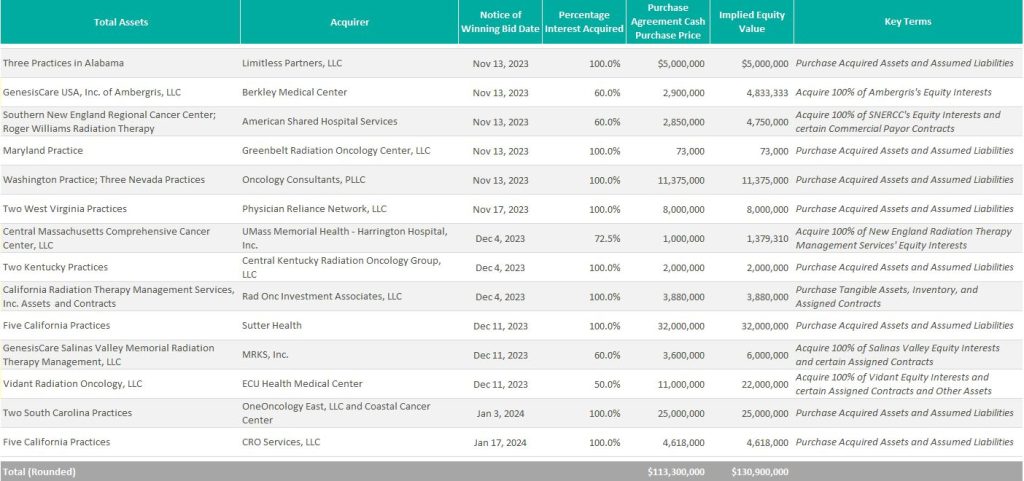

GenesisCare, a prominent provider of cancer services worldwide, filed for voluntary reorganization under Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code on June 1, 2023, in the United States Bankruptcy Court for the Southern District of Texas (Case No. 23-90614). The Australian-based company, once valued at $5 billion and backed by private equity firm KKR, faced financial difficulties due to high debt levels and operational challenges.