- About Us

- Our Clients

- Services

- Insights

- Healthcare Sectors

- Ambulatory Surgery Centers

- Behavioral Health

- Dialysis

- Hospital-Based Medicine

- Hospitals

- Imaging & Radiology

- Laboratories

- Medical Device & Life Sciences

- Medical Transport

- Oncology

- Pharmacy

- Physician Practices

- Post-Acute Care

- Risk-Bearing Organizations & Health Plans

- Telehealth & Healthcare IT

- Urgent Care & Free Standing EDs

- Careers

- Contact Us

Strategic Partnerships in the Inpatient Rehabilitation Industry: Highlights, Opportunities, and Risks

September 5, 2023

By Sydney Richards, CVA, Patrick Speights, and Christopher Tracanna

Approximately 45.0% of acute care discharges are subsequently admitted to a post-acute setting nationwide, including approximately 4.0% who are admitted to an inpatient rehabilitation facility (IRF). An IRF is a freestanding inpatient facility or specialized unit within an acute care hospital that offers intensive rehabilitation to patients after illness, injury, or surgery. Now more than ever, investment demand for IRFs is strong due to the unique value propositions relative to other healthcare verticals, including strong clinical outcomes at an efficient price to payors, a period of stable regulations, rising patient demand, and a high margin for efficient operators.

In response to this demand and the potential for high returns, acute care operators may consider affiliating their existing inpatient rehabilitation units (IRUs) with platform post-acute operators to drive financial returns while improving patient outcomes. IRUs are operated as distinct departments of acute care hospitals, while IRFs are freestanding facilities. Going forward we will use the generic term IRF when discussing the inpatient rehabilitation industry.

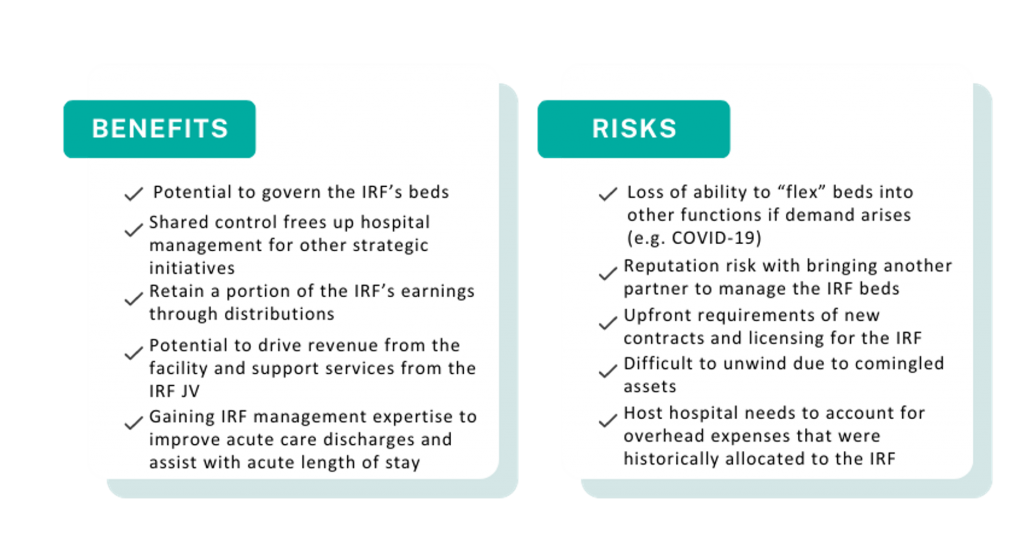

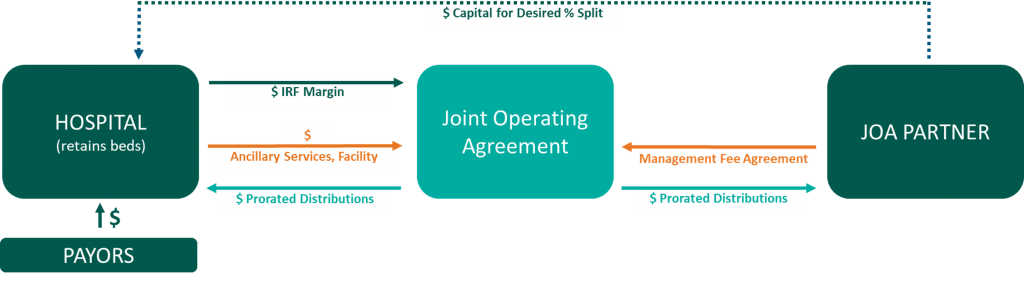

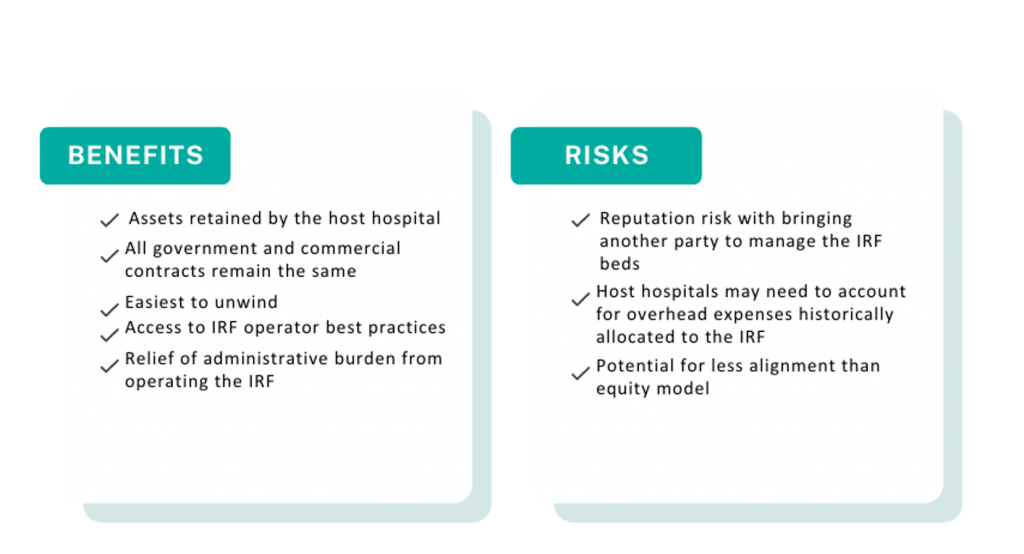

Below, VMG Health experts highlight key industry facts driving up investment. Additionally, our experts detail the potential benefits and risks of common IRF affiliation models, such as joint ventures, joint operating agreements, divestitures, and management agreements.

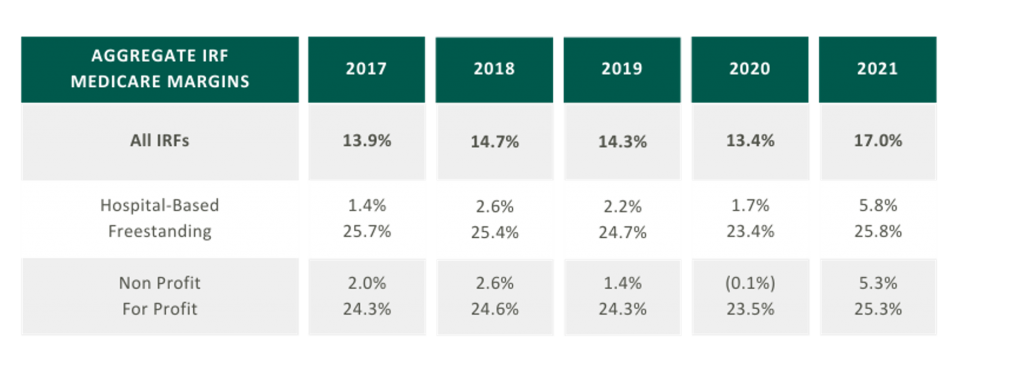

5-Year High Medicare Margins

As presented in the table in the below, aggregated IRF Medicare margins were at a five-year high in 2021 at 17.0%. One driver of this increase is the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) COVID-19 waivers that allowed flexibility in admission criteria and therapy requirements to maintain IRF status. Now that the emergency declaration has ended, margins may become more pressured as IRFs return to standard operating criteria. It is also notable that freestanding Medicare margins were 25.8% in 2021 compared to hospital-based margins of 5.8%. Many factors contribute to this difference, including:

- Scale – Hospital-based IRFs typically have a lower bed count than freestanding IRFs.

- Strategic Differences – Hospital-based IRFs typically support the operations of a broader acute care hospital or health system.

Proliferation of Strategic Post-Acute Buyers; Growth in Freestanding IRFs

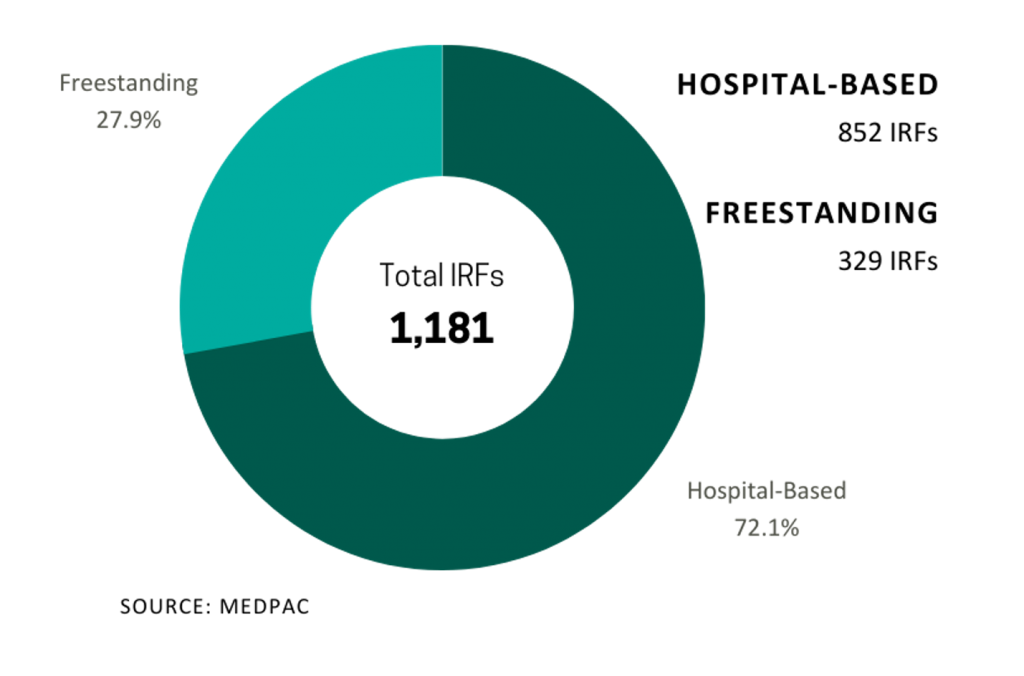

In 2021, five IRFs closed while 22 new IRFs began operations, resulting in a net gain of 17 IRFs. According to MedPAC, the majority of new IRFs were freestanding and for-profit, and most closures were hospital-based nonprofits. As reflected in the chart on the right the top six freestanding IRF operators control approximately 91.5% of freestanding IRFs in the market.

Large Industry with Growing Patient Demand

In 2021, Medicare spent $8.5 billion on 379,000 fee-for-service (FFS) discharges across 1,180 IRFs nationwide. These FFS Medicare stays accounted for approximately 52.0% of IRF discharges on average.

Fragmented

Despite the proliferation of specialized post-acute IRF operators, the IRF industry remains fragmented with over 70.0% of all IRF locations being hospital-based IRUs. The remainder are freestanding facilities. However, based on their relatively larger size and bed counts, freestanding IRFs accounted for approximately 55.0% of Medicare discharges. Additionally, while for-profit IRFs make up about 37.0% of all IRFs, they account for approximately 60.0% of the total Medicare discharges.

Many of the aforementioned factors turned the IRF industry into an attractive sector for a strategic post-acute investor. For acute care systems, collaborating with a post-acute operator can offer significant benefits, including reducing the length of stay and readmission rates, and providing access to clinical and operational best practices. Collectively, these enhancements improve both patient outcomes and financial returns. We have identified several affiliation models for post-acute and IRF unit operators, as well as advantages and disadvantages to consider for each model.

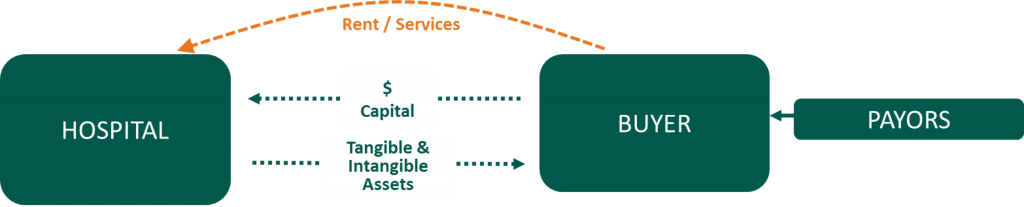

Divestiture

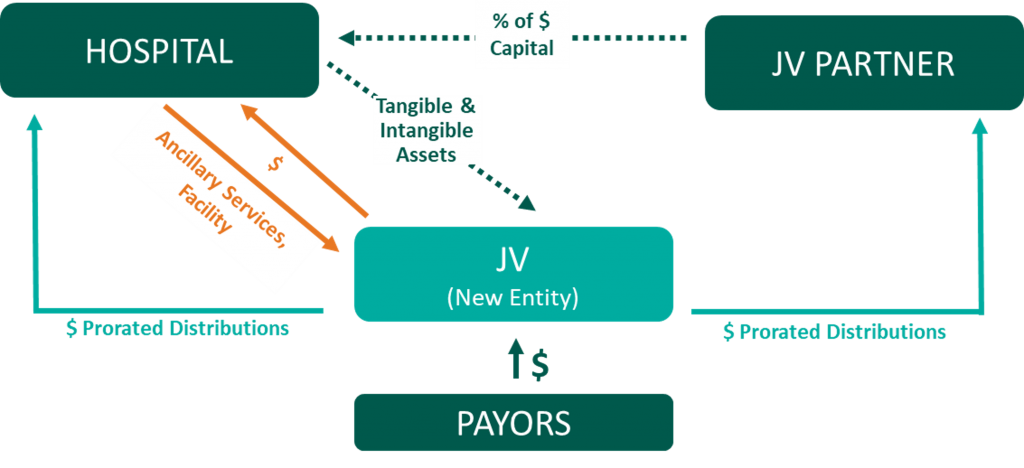

Joint Venture

Joint Operating Agreement

Management Agreement

A post-acute care strategy is vital for acute care providers seeking to elevate patient outcomes while maximizing value to their organization. Forming strategic alliances with post-acute operators in inpatient rehabilitation may be one successful approach. Operators have many avenues to consider whether it is through the sale of an existing inpatient rehabilitation unit, joint venturing with a partner to create a de novo freestanding IRF, or employing a post-acute manager to drive performance in an existing IRF. No matter your path forward, VMG Health experts can provide actionable insights into the value of your existing IRF business and assist with a potential IRF partnership in a model that fits your post-acute strategy.

Sources

- ATI Advisory. (2023, February 10). National Medicare FFS Hospital Discharges to SNF and HHA Trending Toward Pre-Pandemic Patterns.

- Medpac. (2023). Inpatient rehabilitation facility services. Report to the Congress: Medicare Payment Policy.

- Encompass Health Corporation. (2023). Find a location.

- Ernest Health. (2023). Our hospitals.

- Pam Health. (2023). Inpatient Rehabilitation Hospitals.

- Lifepoint Health. (2023). Locations.

- Select Medical. (2023). Locations.

Categories: Uncategorized

The Evolution of Telehealth and What’s Next

August 28, 2023

Written by James Tekippe, CFA and Zach Strauss

For those in the healthcare industry, telemedicine has been viewed as a way to increase access to healthcare, while mitigating the challenges of limited resources of physicians and healthcare providers. Although the use of telehealth has steadily grown over the past two decades, the challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic supercharged this growth. As the United States and the world move beyond the worst months and years of the pandemic, telemedicine usage will continue to change within the industry. This article will explore the state of telehealth immediately prior to and during the early years of the pandemic to provide context for the question, “What will be the next stage of telemedicine in the U.S. healthcare system?”

Telemedicine Prior to the Pandemic

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, many people in the industry believed telemedicine had the potential to make healthcare more accessible, especially for underserved communities. However, in 2016 only 15% of physicians worked in healthcare practices that used telemedicine in any fashion.1 Part of why utilization was low pertained to reimbursement rates. Physicians who utilized telemedicine were not reimbursed at the same level by Medicare as in-person services, and only a limited amount of visit types provided through telemedicine were reimbursable.2,3 In addition, Medicare outlined certain stipulations that allowed providers to use telemedicine for care, including requiring that the provider had a pre-existing relationship with a patient, limiting a provider to only providing services at the practice where they typically provided in-person services, and necessitating the provider was licensed and physically in the same state as the patient being treated.2,4 Finally, the technology used to provide telemedicine had to meet the requirements of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), which required providers to invest in compliant technology to be able to offer care using telemedicine.5

Changes Spurred on by the Pandemic

During 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic became a catalyst that rapidly changed the direction of telemedicine in the U.S. From February 2020 to February 2021 telehealth claims volumes increasing 38x year over year.6 As the world, began implementing lockdown orders in February and March 2020 to limit the spread of COVID-19, legislators in the U.S. looked for a solution to assist the public in accessing the healthcare system while mitigating the public’s fear of contracting this virus. Various solutions were enacted as part of the CARES Act, which was passed in March 2020. These solutions were aimed at increasing the use of telemedicine by healthcare providers. Through CARES, many of the barriers that previously made it harder for providers to adopt the usage of telemedicine were relaxed. This created an unprecedented opportunity for providers to explore the capacity of this medium of care.

First, Medicare changed reimbursement for telemedicine visits to be the same as in-office visits.3 Additionally, physicians were given the ability to reduce, or even fully waive, the Medicare patient cost-sharing for telehealth services which made telemedicine more attractive to patients.3 The CARES Act also removed location barriers and made it possible for providers to see patients who were in different states from the provider during a visit.2 The CARES Act also allowed healthcare providers to offer more types of visits through telemedicine means, like emergency department visits, remote patient monitoring visits, and check-in visits.2 Additionally, providers who historically were not able to provide care through telemedicine, like occupational therapists and licensed clinical social workers, were able to use telemedicine as an option to treat patients.4 Finally, technology HIPAA requirements were relaxed such to allow more two-way audio-visual options, such as Facetime, Skype, Zoom, and audio-only telephonic services for telemedicine visits. This realty increased the ability for providers to offer this service to their patients.2, 5

Current Legislations Impacting the Future of Telemedicine

As the country moves beyond the public health emergency COVID-19 created, the future of telemedicine will depend on whether = regulations revert back to the pre-COVID state. States across the country, from Washington to New Hampshire to Virginia, are introducing legislation to expand telemedicine beyond the CARES Act.7 Despite different geographical locations and political leanings, states seem to agree about telemedicine’s ability to increase access to healthcare. For example, Oregon has introduced legislation to permanently allow out-of-state physicians and physician assistants to provide specified care to patients in Oregon.7 Texas has proposed legislation that would remove the requirement of being “licensed in this state” from an array of licensing and practice requirements for providers to practice telemedicine in the state.7 Virginia has also proposed legislation that offers a solution for telemedicine service provider groups that employ health care providers licensed by the Commonwealth. The legislations would establish that these groups do not need a service address in the Commonwealth to maintain their eligibility as a Medicaid vendor or provider group.7

At the national level, two active bills, HR 4040 and HR 1110, both contain pro-telemedicine legislation. HR 4040, passed by the House in July of 2022, extended certain Medicare telehealth flexibilities beyond the end of the COVID-19 public health emergency (PHE). The bill would allow for Medicare beneficiaries to continue receiving telehealth services in any location they wish until December 31, 2024, or the end of the PHE, whichever comes later..8 In addition, this legislation would continue to grant other healthcare providers, such as occupational therapists and physical therapists, the freedom to continue practicing telemedicine via the CARES Act.8 Finally, behavioral health services, alongside evaluation/management services, would still be allowed via audio-only technology.8 Within the industry, this bill has seen support, specifically from the American Telemedicine Association and the American Counseling Association.7, 9

HR 1110 is a report commissioned by Congress with the explicit purpose of expanding access to telehealth services to Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries.10 Under this legislation, Congress would require that two reports be provided, one by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and the second by the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission (MACPAC) and the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC).10 In the report led by HHS, Congress would require HHS to provide a comprehensive list of telehealth services available during the PHE. This report would include details about the types of providers that could supply these services, a comprehensive list of actions the secretary of the HHS took to expand access to telehealth services, and the reasons for these actions.10 Additionally, this report would require a quantitative and qualitative analysis of the previously mentioned telehealth services, specifically calling out data regarding use by rural, minority, elderly, and low-income populations.10

Regarding the MedPAC and MACPAC report, Congress would require an assessment of the improvements or barriers in accessing telehealth services during the PHE. And in addition, the information MedPAC and MACPAC know regarding the increased risk of fraudulent activity that could result due to expanding telehealth services.10 To conclude the report, Congress has asked both MedPAC and MACPAC to provide recommendations for improvements to current telehealth services and expansions of these services, as well as potential approaches for addressing fraudulent activity previously outlined in the report.10 Ultimately, these reports would be vital in shaping future policies around telemedicine to increase access to and improve the effectiveness of telehealth.

The last few years there have been major changes in many aspects of life, including the ways healthcare is delivered. The U.S. was able to tap into the large potential telemedicine has to offer during the worst stages of the pandemic. However, as we move into the future, it will be important for local and federal governments to continue improving the regulations that impact telemedicine to help expand access.

Sources

- Kane, C., and Gillis, K. (2018). The Use Of Telemedicine By Physicians: Still The Exception Rather Than The Rule. Health affairs (Project Hope) 37(12) (2018): 1923-1930.

- Shaver, J. (2022). The State of Telehealth Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Primary care, 49(4), 517-530.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2020, March 17). Medicare Telemedicine Health Care Provider Fact Sheet.

- American Medical Association. (2020, April 27). Cares Act: AMA COVID-19 pandemic telehealth fact sheet.

- Weigel, G., Ramaswamy, A., Sobel, L., Salganicoff, A., Cubanski, J., and Freed, M. (2020, May 11). Opportunities and Barriers for Telemedicine in the U.S.. During the COVID-19 Emergency and Beyond. KFF.

- Bestsennyy, O., Gilbert, G., Harris, A., and Rost, J. (2021, July 9). Telehealth: A quarter-trillion-dollar post-COVID-19 reality? McKinsey & Company.

- ATA Action. (2023, January 18). ATA Action 2023 State Legislative Priorities.

- H.R.4040 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Advancing Telehealth Beyond COVID-19 Act of 2021.

- American Counseling Association. (2022). ACA Government Affairs and Public Policy: 2022 Year End Report.

- H.R.1110 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): KEEP Telehealth Options Act of 2023. (2023, March 3).

Categories: Uncategorized

Academic Medical Center Growth & Strategic Opportunities

March 13, 2023

By: John Meindl, CFA

Academic Medical Centers (AMCs) are facing unique challenges and opportunities in the current environment. With healthcare systems becoming more complex and dynamic, AMCs are adapting their strategies to preserve their inherent strengths and capitalize on evolving industry dynamics. One of the main challenges facing AMCs is the shortage of physicians, which is predicted to become more acute in the coming years. At the same time, revenue from higher-margin care is eroding as new businesses are capturing market share. As AMCs play an outsized role in solving labor shortages, they have also been forced to adapt to the financial pressures. Here we examine some of the major financial and strategic opportunities available to AMCs.

1.) Academic Medical Center Partnerships

Many successful academic medical centers have adopted a hub-and-spoke model where the AMC serves as the hub and partners with community hospitals, medical complexes, for-profit hospitals, and pure-play service providers as the spokes. This model can improve care coordination to the appropriate site of care while expanding the population basis to support the growth or addition of specialty service lines.

AMCs entering new partnerships are doing so from a position of strength. Typical AMCs have a unique ability to effectively deliver highly complex care. Additionally, most AMCs have a strong and trusted brand in the communities they serve. However, access has long been a traditional weakness with patients struggling to access AMC facilities promptly. To address the access issue while capitalizing on strengths, AMCs are rethinking their approach to partnerships to provide easier channels for reaching their patients. Access to a more diverse population improves patient experiences, lowers cost structures, and provides revenue opportunities. Successful AMC partnerships may even end up being site-of-care agnostic, achieving the most optimum clinical outcomes while compensating all parties for their respective contributions.

However, partnering with non-academic medical centers poses some challenges. AMCs need to ensure that their partners provide the same quality of care and adhere to best practices, while also maintaining the AMC’s own high standards.

2.) Go At It Alone

Well-capitalized AMCs can invest individually in ancillary services to access additional revenue streams and expand their patient base. The right mix of ancillary service lines allow an AMC to expand its footprint, improve clinical offerings, and generate incremental revenue. AMC’s investing in ancillary service lines should consider whether or not to allow the ancillary to use the AMC’s brand name. As outlined below, AMCs typically have a trusted and strong brand name built on a history of excellence. Allowing the ancillary to use the brand can either 1) enhance the volume of ancillary services, 2) dilute the AMC brand name, or 3) a mix of both. Common ancillary services may include ASCs, imaging centers, urgent care, and other retail facilities.

3.) Co-Branding

As mentioned above, AMCs often maintain a strong reputation and brand name. This intellectual property reflects valuable consumer trust built on a history of clinical excellence. With the right strategic partner, AMCs can capitalize on their individual brand to become market makers through brand licensing, co-branding agreements, care network subscriptions, or external affiliations.

Conclusion

By building hub and spoke partnerships with community hospitals and medical complexes, academic medical centers can leverage their inherent strengths to maintain their industry reputation for excellence. AMCs that prefer an individualized approach may choose to invest directly in ancillary services or develop branding or affiliation agreements in order to generate additional revenue streams and expand patient access.

Categories: Uncategorized

Where Are My Earnings? Quality of Earnings Analysis in Post-COVID-19 Urgent Care Transactions

August 16, 2022

Written by Melissa Hoelting, CPA

The COVID-19 pandemic sent shockwaves throughout the urgent care industry and fundamentally changed the business of urgent care centers (UCCs). At the start of the pandemic, UCCs had to quickly adapt to offer a new service line and meet the high demand for COVID tests. As the pandemic has progressed and evolved, UCCs have had to continue to adapt to address the effects of vaccination, variants, and at-home testing to their volumes. In addition to this, they have had to adjust to the changing landscape around reimbursement in regard to government mandates on COVID testing and an increase in new patients. As the pandemic has evolved, the VMG Health Quality of Earnings team has been involved in urgent care transactions and has worked firsthand with our clients to quantify the effect of these changes on EBITDA.

COVID-19 History at Urgent Care Centers

Urgent care centers were at the forefront of treatment and testing services throughout the COVID-19 pandemic. After initial volume disruptions during the early onset of the pandemic, urgent care centers experienced significant increases in testing volumes and new patient visits. Average patient visits per clinic (“APVC”) reached record highs during the summer of 2020 when UCCs ramped up testing capabilities and adopted telehealth services. Overall, UCCs with COVID-19 testing capabilities retained more volume than those without testing capabilities.

In addition to the increased visit volumes, the patient mix between new and established patients shifted. Prior to April 2020, patient mix between established and new visits averaged approximately 60% established and 40% new patients. Following COVID spikes, new patient visits became a greater ratio of total visits and represented over 50% of patient visit mix after April 2020 and into 2021. This mix shift had an impact on reimbursement for many urgent care centers. Clinics saw an increase of 52.0% in average net revenue per visit in 2020 as new patients were reimbursed at a higher rate than established patients. This was partially offset by a rise in “no-visit” patients where an E&M code was not billed (e.g., only testing services performed).

During January 2022, through funding from the American Rescue Plan, at-home COVID testing kits were offered online for free. As of May 2022, over 70 million households have visited COVIDTests.gov to order free at-home tests and 350 million tests have been delivered through the program. The program has offered several rounds of free at-home testing mailed through USPS, and eight additional tests were approved for distribution as of May 17, 2022. In addition, pharmacies, online stores, (e.g., Amazon), and retail locations have expanded the accessibility of at-home testing kits.

Volume-Related Quality of Earnings Adjustments

To quantify the impact of these trends on an urgent care center’s quality of earnings, we must first distinguish between the three types of visits – asymptomatic COVID visit, symptomatic COVID visit, and traditional urgent care visit. Many UCCs now require an office visit whenever a COVID test is administered, therefore we cannot solely use CPT codes to separate between asymptomatic and symptomatic visits but instead must rely on the ICD-11 codes. Based on ICD-11 codes, asymptomatic COVID visits include patients who only have a COVID test code and, in some cases, a comorbidity code such as having high blood pressure, being a smoker, etc. Symptomatic COVID visits include both a COVID test code and symptom codes (i.e., cough, sneeze, sore throat, etc.). Finally, traditional UCC visits include all remaining visits. Once these visits have been categorized we can begin adjusting to expected go-forward volumes.

First, we evaluate the appropriate run-rate of asymptomatic COVID testing. At the start of the pandemic, few individuals received an asymptomatic COVID test since facilities often experienced shortages of tests and chose to prioritize symptomatic patients. In 2021, asymptomatic testing increased as individuals sought testing to meet requirements imposed for travel, employment, and other reasons. Recently, asymptomatic testing demand has fallen (decreased?) as many cities, states, and countries have either eliminated testing requirements or replaced them with vaccine requirements. Due to the changing landscape of asymptomatic testing, we use a narrow time frame of three to six months to determine the appropriate run-rate volume.

Next, we determine the go-forward state of symptomatic COVID testing. Before the prevalence of vaccines, symptomatic COVID testing dominated UCC volume. At this time, the only downward pressure on volume came from supply shortages. After widespread availability of vaccines in early 2021, UCCs began to experience periods of both high and low demand for symptomatic testing as new variants began to emerge. In addition to this more seasonal nature of demand, at-home testing became more prevalent, and was further accelerated by the funding from the American Rescue Plan in January 2022. Based on all these factors, we use a look back period of eight to 12 months for calculating average go-forward volume. This timeframe ensures we capture seasonality while only including months with similar circumstances regarding vaccinations and at-home testing.

Finally, we evaluate the expected recovery of traditional urgent care volume. During the period of stay-at-home orders in 2020, UCCs saw a large fall off in non-testing volume. This was especially prevalent as many facilities temporarily became COVID-only sites. After stay-at-home orders were lifted, facilities still saw lower non-testing volume due to other restrictions put in place such as mask mandates and social distancing. These restrictions resulted in a milder cold and flu season at the time. As traditional volumes remain depressed, 2019 represents the ideal benchmark for estimating future urgent care volume as it is the last year untouched by COVID.

However, relying on 2019 volumes to determine a new run-rate comes with its own challenges stemming from capacity constraints, hiring challenges, and volume trends. In 2019, most UCCs were ideally operating close to full capacity with only traditional visits. Thus, we need to balance expected COVID test volume with a return to normal to ensure we do not project total monthly volume beyond the capacity of a location. Additionally, many UCCs have reported hiring challenges due to the shortage of nurses and mid-level providers which make up the bulk of staff for most facilities. We address this challenge to our calculation by holding conversations with management to understand the specific facility’s hiring challenges and to determine if traditional capacity needs to be reduced. Finally, as of April 2022, Experity reported that non-COVID visit volumes were only at 72% of pre-COVID levels. This trend means we cannot peg a complete return to pre-COVID levels because volumes have not recovered despite life returning to normal in many states. With all these challenges, we can no longer use 2019 as a benchmark since the landscape of urgent care volume mix has changed dramatically over the last two and a half years. As a result, we elect to use the average of the last six to eight months to capture seasonality and current trends. Although these volumes trend lower than 2019, they reflect the changing reality of the volume mix and capacity concerns.

Once we have determined go-forward monthly volumes for the three test types, we can make the appropriate quality of earnings adjustments. We begin by creating cash waterfalls for each volume type to calculate accrual basis revenue. Using this revenue, we calculate the historical average reimbursement for each visit type. Due to changing reimbursement trends for COVID testing and office visits in recent years, we use the average of the last six months in our calculation of adjusted revenue. Once we have determined the revenue adjustment, we estimate the associated variable expense impact for each visit type based on common size percentages, direct allocation, and invoice review. Volume estimates are the key to the calculation of both the revenue and expense adjustments, which emphasizes the importance of reasonable estimates.

Additional COVID-Related Quality of Earnings Adjustments

Besides impacting urgent care volume and mix, COVID-19 also impacted the ramp up of de novo facilities opened just before and during the pandemic. Average startup location volumes historically averaged between 10 to 20 visits per day in the first six months of operations for de novo locations opening between 2016 and 2019. Volumes for these locations stabilized at approximately 30 – 40 patients per day after 18 to 24 months. However, startup locations that opened in 2021 saw an average of 32 patients per day in the first month, and 60 visits per day after just six months.

For a quality of earnings analysis, the changes to the ramp up of de novo facilities create a challenge for quantifying a run-rate adjustment. First, there are concerns about sustainability of patient volume as COVID testing declines. In the beginning of the pandemic, shortages of tests meant individuals sought tests wherever possible even if it meant traveling to a further center. Some parent companies even made de novo locations into COVID-only sites to raise awareness of the new location. As a result, some patients may return to a different location for future visits which creates uncertainty when estimating the impact of a return of traditional urgent care volume. To combat this challenge, we engage in discussions with management to identify existing sites that serve a similar demographic and can be used as the volume being averaged to calculate run-rate.

The case mix changes also cause issues in conducting a revenue hindsight analysis. Due to government mandates around reimbursement for COVID testing, UCCs experienced higher reimbursements for patients getting a COVID test since many payors were obligated to pay all claims. Additionally, many COVID tests were administered either with no office visit or with an office visit of a lower E&M code level than typical. Furthermore, UCCs that did require an office visit often saw new patient visits becoming a greater ratio of total visits following COVID spikes and new patients represented over 50% of patient visit mix after April 2020 and into 2021. This patient mix shift drove an increase in average net revenue per visit for many UCCs. Finally, stay-at-home orders and people working from home have driven a slowdown in reimbursements from payors. As a result, historical collection trends were skewed during 2020 and into 2021. All these factors necessitate a close analysis of the revenue data for UCCs which often entails performing separate analysis by visit type (i.e., test vs. non-test) or CPT code (i.e., new patient vs. established). Due to the changing landscape of patient and visit type mix since the beginning of the pandemic, the revenue hindsight analysis has become a large area of focus for all parties to the transaction.

Typically, the last, most straightforward adjustments we perform in our analysis center on non-recurring COVID revenue and expenses such as CARES Act funding and rent abatement. Many UCCs participated in the various economic relief programs and received Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) loans, HHS stimulus grants, Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL), etc. As these amounts were received or forgiven, many UCCs recognized the amounts as income. Additionally, UCCs often took advantage of temporary rent or payroll tax abatements that were recaptured or will be recaptured at a later date. These amounts represent non-recurring or temporary measures, and we always include adjustments to eliminate their impact from earnings.

Conclusion

With all these complications and uncertainties arising from COVID testing, both buyers and sellers in the UCC market need to engage a quality of earnings team for their transactions. Over the last two and a half years, the outlook of COVID and testing has changed week-to-week and month-to-month. During 2021, our team was engaged as a sell-side advisor and conducted an original analysis in addition to two roll forwards for one client. Each of our analyses was at a different point in 2021 and each analysis had unique trends around vaccination, variants, and seasonality. By engaging a quality of earnings team, our client was able to get a deeper analysis of its earnings to quantify the effects of this changing landscape on its EBITDA. From the expansion of at-home testing to the potentially permanent depression of traditional volume, quality of earnings will be crucial in analyzing the changing nature of the COVID and UCC landscape as we continue to return to normal.

Categories: Uncategorized

OIG Puts the Spotlight on Practitioner Arrangements with Telemedicine Companies in a Special Fraud Alert

July 21, 2022

By: Bartt Warner, CVA and Dane Hansen

The Office of Inspector General (OIG) and Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) released a Special Fraud Alert (Alert) on July 20, 2022 related to the inherent fraud and abuse risk associated with physicians or other health care professionals entering into arrangements with telemedicine companies (Telemedicine Companies).1 Specifically, addressing fraud schemes related to telehealth, telemedicine, or telemarketing services based on dozens of civil and criminal investigations. The Alert identified seven characteristics that the OIG believes could suggest a given arrangement has potential risk for fraud and abuse. However, the OIG was cautious not to state that all Telemedicine Companies and arrangements are suspect, but rather to identify key characteristics in potentially problematic arrangements as the prevalence of telehealth services continually increases. In addition, the Alert was designed to provide practical compliance guidance and help establish guardrails with relation to telemedicine arrangements. Simultaneously, the OIG also updated its Telehealth Resource Page2 which aggregates compliance and enforcement resources.

Kickbacks

The Alert provided a specific example of how Telemedicine Companies have utilized kickbacks to aggressively recruit and reward telemedicine practitioners to further their fraud schemes. According to the example:

“…in some of these fraud schemes Telemedicine Companies intentionally paid physicians and nonphysician practitioners (collectively, Practitioners) kickbacks to generate orders or prescriptions for medically unnecessary durable medical equipment, genetic testing, wound care items, or prescription medications, resulting in submissions of fraudulent claims to Medicare, Medicaid, and other Federal health care programs. These fraud schemes vary in design and operation, and they have involved a wide range of different individuals and types of entities, including international and domestic telemarketing call centers, staffing companies, Practitioners, marketers, brokers, and others.”

Based on the OIG’s experience with fraud and abuse in this realm, the Telemedicine Companies often work out an arrangement with the Practitioners to order and prescribe medically unnecessary items and services. Oftentimes, the Telemedicine Companies pay the Practitioners for prescribing items or various services to patients who have had limited interaction with the Practitioner and without regard to the medically necessity for this service or prescription. In addition, these kickbacks are routinely disguised as payment per review, audit, consult, or for the assessment of medical charts and are often tied to the volume of federally reimbursable items or services ordered or prescribed by the Practitioners. As a result, the fees associated with the problematic arrangements are being used as a mechanism to incentivize a Practitioner to order medically unnecessary items or services according to the Alert. Of additional concern, the OIG noted that in many cases the Telemedicine Companies sell the prescriptions that are generated by the Practitioners to other entities who in turn will fraudulently bill for the medically unnecessary items or services.

Compliance Risk

The OIG makes it clear in the Alert that these fraudulent telemedicine schemes pose a significant risk to the health care system and that both Practitioners and health systems should exercise extreme caution when entering into arrangements with Telemedicine Companies. Specifically, the Alert stated,

“These schemes raise fraud concerns because of the potential for considerable harm to Federal health care programs and their beneficiaries, which may include: (1) an inappropriate increase in costs to Federal health care programs for medically unnecessary items and services and, in some instances, items and services a beneficiary never receives; (2) potential to harm beneficiaries by, for example, providing medically unnecessary care, items that could harm a patient, or improperly delaying needed care; and (3) corruption of medical decision-making.”

These telemedicine schemes have the potential for violating multiple Federal Laws, but most specifically, the Federal anti-kickback statute. Violations of the Federal Anti-kickback statute ascribes liability to both sides of the arrangement and can potentially lead to criminal, civil, or administrative liability under other Federal laws as well.

Suspect Characteristics

Based on the OIG’s experience with various problematic telemedicine arrangements, seven “suspect characteristics” were identified that taken together, or separately, could suggest an arrangement presents a heightened risk for fraud and abuse. However, it should but noted that the list is not exhaustive, but rather illustrative and the presence or absence of these characteristics does not determine if a particular telemedicine arrangement would constitute grounds for legal sanctions.

- “The purported patients for whom the Practitioner orders or prescribes items or services were identified or recruited by the Telemedicine Company, telemarketing company, sales agent, recruiter, call center, health fair, and/or through internet, television, or social media advertising for free or low out-of-pocket cost items or services.

- The Practitioner does not have sufficient contact with or information from the purported patient to meaningfully assess the medical necessity of the items or services ordered or prescribed.

- The Telemedicine Company compensates the Practitioner based on the volume of items or services ordered or prescribed, which may be characterized to the Practitioner as compensation based on the number of purported medical records that the Practitioner reviewed.

- The Telemedicine Company only furnishes items and services to Federal health care program beneficiaries and does not accept insurance from any other payor.

- The Telemedicine Company claims to only furnish items and services to individuals who are not Federal health care program beneficiaries but may in fact bill Federal health care programs.

- The Telemedicine Company only furnishes one product or a single class of products (e.g., durable medical equipment, genetic testing, diabetic supplies, or various prescription creams), potentially restricting a Practitioner’s treating options to a predetermined course of treatment.

- The Telemedicine Company does not expect Practitioners (or another Practitioner) to follow up with purported patients nor does it provide Practitioners with the information required to follow up with purported patients (e.g., the Telemedicine Company does not require Practitioners to discuss genetic testing results with each purported patient).”

Best Practices

Given the heightened regulatory scrutiny placed on telehealth service arrangements by the OIG and HHS, it is pertinent for health systems, hospitals, and Practitioners to employ certain best practices when considering, implementing, and operating any type of virtual care program. Many of the best practices for traditional face-to-face professional services arrangements are directly applicable to telemedicine arrangements. For example, a telehealth arrangement should be justifiable for all parties involved. From the perspective of a health system or hospital for example, the addition of a virtual care service line could be pursued to fill a highly desired gap in medical care, increase the quality of medical care currently available to its patient base, or alleviate overburdened Practitioners.

Prior to entering any business relationship for telehealth services, it is a best practice to consult with legal counsel. Telemedicine service contracts should be explicit in outlining the expectations of medical care and the structure and magnitude of remuneration. Further, it is particularly important to maintain ongoing dialogue with legal counsel throughout the life of a telemedicine relationship to ensure that a program that was once compliant does not break the bounds into non-compliance over time. Preserving a compliant telehealth business relationship is typically aided by a robust compliance program, created with the help of legal counsel, which outlines specific guidelines for professional examinations, prescribing and billing practices, administrative and record maintenance procedures. Compliance programs should be consistently reviewed and updated as regulatory bodies issue more literature on the subject matter. A static compliance program may quickly become inadequate as the virtual care regulatory landscape continues to evolve. Obtaining third party support of an arrangement is often a pillar of successful compliance programs. The arrangement should be commercially reasonable to all parties involved and any compensation should be directly attributed to services performed and have no consideration of referrals. Obtaining a third-party fair market value (FMV) review is a key best practice in maintaining regulatory compliance within the context of telemedicine arrangements. In addition, seeking a third-party commercial reasonableness assessment should also help mitigate compliance risk by documenting and assessing both qualitative and quantitative factors as to why the telemedicine arrangement is a sensible and prudent business decision without the consideration of referrals.

Conclusion

Although the Special Fraud Alert addresses that it is not intended to discourage legitimate telemedicine arrangements, serious compliance risk may occur if an arrangement has any of the seven “suspect characteristics” as previously discussed. In addition, the OIG made it clear that Practitioners have both legitimately and appropriately utilized telehealth services to provide medically necessary care to their patients during the current public health emergency. Best practices should include a cautious approach to telemedicine arrangements while ensuring there are specific guidelines and guardrails, determining and documenting the justification for the arrangement, ensuring the arrangement is commercially reasonable, and determining if the remuneration paid to the Practitioners is consistent with FMV.

Endnotes

1 Special Fraud Alert: OIG Alerts Practitioners To Exercise Caution When Entering Into Arrangements With Purported Telemedicine Companies available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/documents/root/1045/sfa-telefraud.pdf

2Telehealth Featured Topic from HHS and the OIG available at: https://oig.hhs.gov/reports-and-publications/featured-topics/telehealth/

Categories: Uncategorized

Authors

Is There Value in Your Inpatient Rehabilitation Facility?

By: Sydney Richards, CVA and Stephan Peron, CVA Inpatient rehabilitation utilization has experienced remarkable growth over the past decade, fueled...

Learn More