- About Us

- Our Clients

- Services

- Insights

- Healthcare Sectors

- Ambulatory Surgery Centers

- Behavioral Health

- Dialysis

- Hospital-Based Medicine

- Hospitals

- Imaging & Radiology

- Laboratories

- Medical Device & Life Sciences

- Medical Transport

- Oncology

- Pharmacy

- Physician Practices

- Post-Acute Care

- Risk-Bearing Organizations & Health Plans

- Telehealth & Healthcare IT

- Urgent Care & Free Standing EDs

- Careers

- Contact Us

Navigating Value-Based Care: Insights from Nicole Montanaro at the ABA Emerging Issues in Healthcare Law Conference

May 2, 2024

At VMG Health, we’re dedicated to sharing our knowledge. Our experts present at in-person conferences and virtual webinars to bring you the latest compliance, strategy, and transaction insight. Sit down with our in-house experts in this blog series, where we unpack the five key takeaways from our latest speaking engagements.

1. Can you provide a high-level overview of what you spoke about at the American Bar Association Emerging Issues in Healthcare Law Conference?

I spoke with King and Spalding attorney Kim Roeder on different, hot-button issues that arise when structuring and valuing different value-based arrangements. It started off as a presentation of different case studies and focused on what Roeder has encountered from a legal perspective and what I have encountered from a valuation perspective. We often receive questions when it comes to structure or even value drivers, and we wanted to present solutions to what we saw or clients struggling with so that they could develop a better understanding of them.

2. What do you think the audience was the most surprised to learn from your presentation?

The focus on the metrics themselves and how carefully they need to be considered seemed to be the most surprising. Recent regulations have been really focused on metrics, and that’s what we get the most questions about. I think our audience was also surprised to learn that Kim had experienced those questions as well, and metrics aren’t just a consideration on the valuation perspective. Both legal and valuation perspectives must carefully consider metrics.

3. How do you think your presentation helped healthcare leaders better prepare for challenges?

Our presentation was a very pragmatic way of illustrating six key issues that often come up during valuation. It’s a great resource for healthcare leaders to reference as they go through and check the boxes to ensure they have thought through all of the considerations that we often see as eleventh-hour issues.

4. What resources would you suggest for those interested in learning more?

I co-wrote a section of the 2023 Physician Alignment: Tips and Trends Report that discusses quality incentives for providers. It captures key factors to consider, from a valuation perspective, when looking to enter value-based arrangements and where to start.

5. If someone takes only one message from your presentation, what would you want it to be?

Value-based arrangements require a very orchestrated balance between legal and compliance, operational champions, and valuation teams. Operational teams should be able to focus on what changes and improvements they want to implement, valuation teams must have an understanding of those goals, and legal and compliance must be involved to ensure the approach is appropriate and compliant. Without cohesion between these three groups, we see those eleventh-hour issues pop up.

Our team serves as the single source for your valuation, strategic, and compliance needs. If you would like to learn more about VMG Health, get in touch with our experts, subscribe to our newsletter, and follow us on LinkedIn.

Categories: Uncategorized

Trouble in Paradise? Disputes, Divorce, and Damages

April 3, 2024

Written by Ingrid Aguirre, CFA

The formation of any business partnership typically begins with an eager commitment by each party to pursue a particular goal, business, or venture. Often, the endeavor begins with an eagerness and readiness to overcome growing pains and challenges at the onset. However, some challenges cannot be overcome, and instead, they may exacerbate what turns into a tenuous relationship. Healthcare partnerships are not exempt from these challenges. Over its almost 30-year history of serving healthcare clients, VMG Health has been engaged to perform a variety of damage analyses and provide its expert witness services, including, but not limited to, disputes, divorces, and commercial damages. These damages are often in the form of diminution of business value or lost profits. VMG Health has served as a trusted advisor to its clients amid these challenging situations.

Disputes

Ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs) are one such example where disputes may arise. With at least 11,000 surgery centers nationwide and with multiple partners at each of these surgery centers, there are many instances where disputes arise among partners (often consisting of physicians, health systems, and management companies). Typical to any business where partners come and go, physicians will buy in and buy out of surgery centers. This opens the door to disputes in situations where one partner is offered a purchase price that may not be appropriate. Alternatively, a physician may be forcibly redeemed of her shares. Inevitably, the greater the number of partners, combined with human nature, the greater the likelihood of an eventual dispute. Of course, disputes are certainly not specific to surgery centers but remain an ever-present adversity insofar as human fallibility exists.

In these disputes, it is typical to engage attorneys who subsequently may engage healthcare expert appraisers to determine the value of the interest in question. A few examples, specific to surgery centers, whereby VMG Health has provided its expert opinion, and in some cases, expert witness testimony on, are as follows:

- Surgery center dispute whereby the relationship between physicians and the operator soured, resulting in the physicians abandoning the surgery center and damaging the operator owner’s interest.

- Surgery center dispute where the buy-out price for a non-controlling interest was in question.

- Surgery center where a physician owner was inappropriately terminated without cause.

- Surgery center where distributions were inappropriately withheld by one of the owners.

Divorce

Marital dissolution has its challenges and unique considerations. One key component is determining the allocation of community assets among both spouses. The challenges lie in determining the value of private interests that either spouse may own. This may take the form of the entirety of a privately held business (e.g., physician practice or lab company) or an interest in a smaller, yet still private, business (e.g., interest in an ASC). Regardless of the interest owned, it is imperative to determine the value of a private business for the purpose of a marital dissolution.

Unlike other disputes among business partners, a marital dissolution has its nuanced challenges that an appraiser must understand. First, an appraiser must understand state specific requirements, through discussions with legal counsel, regarding any statutory regulations on equitable distribution. Some states follow the policy of equitable distribution, which requires a fair allocation of the assets between spouses at the time of a divorce. It is necessary to understand the jurisdiction, particularly if the state does not require equitable distribution. Second, an appraiser must understand personal goodwill. Personal goodwill may be defined as the value created and attributed to an individual’s efforts. As an example, personal goodwill may be applied to a physician owner. However, understanding that the business itself may have goodwill, it is important that the appraiser separate enterprise goodwill from personal goodwill, as applicable. Quantifying personal goodwill is necessary to understand when providing an opinion for purposes of a marital dissolution. Third, the valuation date must be defined following discussions with legal counsel. In a marital dissolution, the valuation date may be based on the date of separation, the date of filing or the date of trial.

VMG Health has provided expert opinions, and in some cases, expert witness testimony, on a variety of marital dissolutions, including, but not limited to, the following:

- Marital dissolution of a provider owning interest in a pain management business, a surgery center, and pharmacies.

- Marital dissolution of a physician owning a primary care business.

- Marital dissolution of a physician owning interest in a surgery center.

- Marital dissolution of a physician with a healthcare product in development.

- Marital dissolution of an owner of a home care business.

Damages

Last, not too dissimilar from a marital dissolution, a partnership between business owners or other parties that are contractually aligned may also fracture. The quantification of damages may take the form of a valuation, a calculation of value, or a lost profits analysis. Due to the unique nature of each damage engagement, it is imperative to define and quantify the damage appropriately. This also requires the valuation expert to work closely with the client’s legal counsel.

Lost profits and damages calculations have been performed by VMG Health along with expert witness services in a variety of scenarios, including, but not limited to the following:

- Lost profits calculation for a franchisor violating its agreement with a franchisee.

- Lost profits calculation regarding an agreement between a payor and health system.

- Calculation of patient revenue lost attributable to an unauthorized letter distributed to former patients.

- Calculation of damage whereby all physician owners left the practice and its original owner to form a competing practice; a non-compete was not in place.

- Calculation of damages to a practice whereby the sale price of the practice was inflated due to upcoding of evaluation and management codes prior to the sale.

Conclusion

In the intricate landscape of disputes, divorces, and damages, navigating the complexities can be a daunting challenge. VMG Health understands the toll these situations may take both emotionally and financially. When faced with these difficult situations, it is crucial to entrust your needs to valuation experts aligned with your needs. VMG Health provides valuation and damages guidance through these litigated and dispute resolution matters.

Sources

Wallace, C. (2023). Number of ASCs in the US outpaces CMS’ estimates. Becker’s ASC Review. https://www.beckersasc.com/asc-news/number-of-ascs-in-the-us-outpaces-cms-estimates.html

Cornell Law School. (2021). equitable distribution. In Legal Information Institute. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/equitable_distribution

Schmidt, J. (n.d.). Personal Goodwill. CFI. https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/valuation/personal-goodwill/#:~:text=Personal%20goodwill%20is%20the%20intangible,and%20not%20the%20business%20itself

Categories: Uncategorized

Exploring the World of Value-Based Care: An Overview

November 3, 2023

Written by Tyler Perper and Matthew Marconcini, CPA

The following article was published by Becker’s Hospital Review.

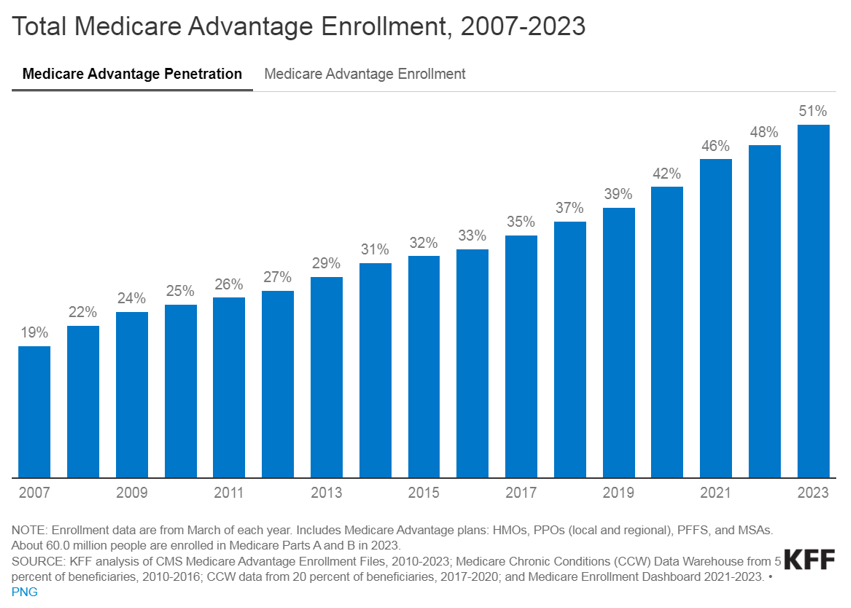

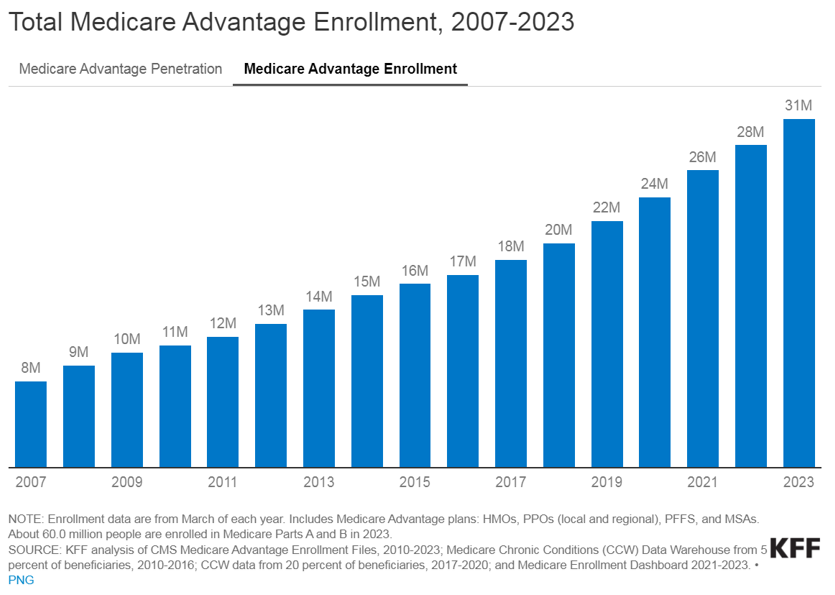

The landscape of healthcare is continually evolving, with a growing emphasis on providing better outcomes for patients while controlling costs. Value-based care (VBC) is a departure from the traditional fee-for-service (FFS) model and is transforming healthcare delivery into a capitated model that balances the total cost of care with the quality of patient outcomes. Investment within VBC or alternate payment models (APMs) quadrupled from 2019 to 2021, while investment in legacy-care delivery models has remained relatively flat. Additionally, the estimated number of Medicare enrollees participating in Medicare Advantage (MA) plans is expected to increase by more than 24% in 2023 compared to the 2022 MA enrollment growth. The explanation for the significant VBC investment and the growth in VBC players is primarily driven by the acknowledgment amongst U.S. policymakers, providers, and payers that VBC offers a sustainable model of care for patient populations across the country, as well as the opportunities presented by new technology and tech-enabled services that facilitate VBC for both providers and payers.

Understanding VBC

VBC is a payment model that incentivizes healthcare providers to focus on delivering high-quality care while containing the costs. Unlike the FFS payment model, in which providers are reimbursed based on the number of services they render, the APM model encourages providers to prioritize the patient’s health and well-being by promoting preventive measures, care coordination, and better health outcomes. In addition, as providers transition to value-based care their reimbursement model aligns more closely with that of payers. This shift requires providers to gain a fundamental understanding of the expertise needed for managing risk, similar to payers.

Managing risk and risk sharing in healthcare refers to the practice of distributing and managing the financial risks associated with healthcare services among different stakeholders, such as insurers, healthcare providers, and sometimes patients. It involves mechanisms and arrangements designed to ensure the financial burden and responsibility for healthcare costs are shared rather than being shouldered entirely by one party. The goal is to promote cost efficiency and improve healthcare quality.

Transitioning to VBC reimbursement models presents providers with a spectrum of options. At the outset, pay-for-performance models link claims reimbursement to quality and value. This means that providers are reimbursed using a fee-for-service structure while qualifying for value-based incentives or penalties based on quality and cost performance. Such models are particularly favorable for smaller practices lacking extensive health IT and data analytics infrastructure.

Moving further along the spectrum, shared savings arrangements offer higher financial rewards and allow providers to retain a portion of the savings if they reduce healthcare spending below established benchmarks. Shared risk models, where providers must cover healthcare costs exceeding benchmarks, foster greater accountability, especially within accountable care organizations.

Finally, capitation payments place full financial risk on providers and offer either global capitation with a fixed payment for all services or partial capitation covering specific services with all other care reimbursed through fee-for-service. While capitation models provide prepaid reimbursements and an incentive for innovation, they present challenges related to quality measures and data sharing. Overall, this spectrum allows providers to select the most suitable value-based reimbursement structure to enhance revenue and adapt to evolving healthcare reimbursement models.

VBC Considerations by Payer Type

Medicare, including both MA and traditional Medicare, serves as a hub for VBC innovation in the United States. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is the largest payer in the healthcare system and holds significant influence in shaping industry standards and promoting the adoption of APMs. The elderly population, which is covered by Medicare, tends to have higher rates of illness and multiple health conditions. This, coupled with the long-term coverage provided by Medicare, makes VBC interventions particularly impactful in reducing the cost of care for these patients.

Within traditional Medicare, the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) is a widely participated program. The program offers mild shared savings and shared-risk arrangements. The more intensive-risk ACO REACH program attracts more sophisticated VBC providers that are often engaged in MA-capitated contracts.

Currently, VBC is not as common within the Medicaid and commercial markets on a national basis for numerous reasons. For Medicaid, the lower rates of reimbursement (in comparison to Medicare and commercial payers) limit the VBC capitated care model. Also, the high fragmentation of Medicaid regulation from state to state limits the scalability of the APMs. There is a high level of enrollee turnover within Medicaid programs which makes it more difficult to understand individual patient populations over the course of time.

The lack of implementation within commercial markets is due to one main reason: the demographic profile of a typical commercial patient (skewed younger and of higher socioeconomic status) leads to lower health risks. This means that investing a dollar in primary care for a commercially insured individual results in lower, less substantial total cost of care savings compared to Medicare or Medicaid patients. However, the traction of Medicaid and commercial patients in risk-sharing arrangements depends on the market across the U.S. In certain markets, such as California, risk-based arrangements are more common due to the early adoption of health maintenance organizations and the way those programs have shifted into risk-bearing organizations. As data analytics improves and payor-provider convergence continues, the development of Medicaid and commercial VBC structures is increasing.

The Ever-Changing Group of VBC Players

In the traditional FFS models, the primary relationship was between payors and providers. The shift towards value-based care has led to the evolution of the players involved. These relatively novel VBC participants can be categorized into three main groups, each with its own subcategories.

Many of the prominent VBC players fall within the provider management category. This category aims to back or acquire medical practices operating within VBC frameworks. There are several models that facilitate VBC provider management. There are those operators who seek to establish new clinics and healthcare practitioner recruitment by prioritizing consistent branding and patient experience while tackling capital-intensive challenges.

Other operators contract directly with self-insured employers by offering comprehensive primary care services that often include behavioral health and pharmacy, and by promoting clinic growth through employer contracts. Another provider management model of VBC is the acquisition of provider groups. This model transitions them into physician-owned primary care practices and shifts the revenue toward taking on riskier VBC contracts. Lastly, there are operators that focus on taking specialty practices, such as orthopedics, oncology, or nephrology, and transitioning them into VBC contracting. This is done by leveraging specialty-based operational sophistication and specific specialty VBC payment models.

The second category of VBC players comprises organizations that opt for collaboration with independent providers or medical groups rather than acquiring practices outright. These entities, often referred to as “VBC enablers,” play a pivotal role in facilitating the transition to value-based care. They offer a comprehensive suite of services, including advanced technological solutions, expert consulting, and various forms of support. Through their involvement, these enablers actively engage in the shared risk associated with value-based contracts, demonstrating their commitment to advancing healthcare transformation and fostering a culture of collaboration and innovation. By forging these strategic partnerships, VBC enablers empower independent providers and medical groups to navigate the complex landscape of value-based care successfully, ultimately improving the quality and efficiency of healthcare delivery for all stakeholders involved.

The third category encompasses the technological solutions and ancillary services that play a pivotal role in facilitating the shift from FFS to VBC. There are many different players within this category and the technology-based solutions these companies provide include patient population/risk management, care coordination, surgery coordination, outcomes measurement, and care management. Patient population management is software that helps providers track patient health outcomes, utilization patterns, and risks. It aids in identifying high-risk patients and implementing interventions to reduce costs. Care coordination is the technology behind building quality referral networks, ensuring closed-loop referrals, and sharing patient information among care providers. Surgery coordination is software used to orchestrate surgeries efficiently and manage costs, especially in a VBC context. Outcomes measurement highlights the importance of understanding the quality metrics of the care provided and managing costs of care. Furthermore, care coordination is what guides patients through the healthcare system to improve outcomes and minimize costs. This includes services for chronic condition management and care navigation. These players can provide one or multiple of the services previously described and often contract with other entities in the VBC environment.

Benefits of Value-Based Care

The transformation towards VBC healthcare delivery models holds the promise of significant benefits that extend to both cost reduction and the enhancement of satisfaction among providers and patients alike. By concentrating on preventive measures and evidence-based treatments, VBC stands to ameliorate health outcomes and particularly benefit patients with chronic conditions. Furthermore, it promotes the efficient allocation of resources, thereby generating cost savings for both patients and healthcare systems, in particular. One pressing issue is the high rate of hospital readmissions, and it requires attention because it is. Currently hovering at approximately 15% within Medicare. Through an increased emphasis on care coordination and follow-up care, VBC aims to mitigate the frequency of avoidable hospital readmissions. Additionally, it underscores the importance of the patient’s experience and positions the patient at the core of the healthcare process. This ultimately results in heightened patient satisfaction and engagement. Lastly, it addresses physician satisfaction by reducing resource utilization while potentially maintaining reasonable compensation levels. Ultimately, VBC stakeholders expect to create a healthcare system that is more sustainable and centered around the needs of patients, while unlocking profitability and returns for investors.

Challenges & Considerations

Although promising, VBC presents its own set of challenges for providers and payers alike. Effective VBC relies on robust data collection and analysis capabilities which necessitates technological infrastructure upgrades for many healthcare organizations. Additionally, determining meaningful quality metrics for specialty care can be intricate due to the specificity of outcome measures required for different conditions. Providers may encounter financial risks if they fail to meet VBC targets, particularly in shared savings or full risk-sharing arrangements. Ensuring alignment of incentives among various stakeholders, including physicians, hospitals, and payers, is pivotal to the initiative’s success. These challenges must be navigated to fully realize the potential benefits of VBC.

Conclusion

Despite the significant hurdles in the way, the healthcare market’s accelerating shift to VBC signifies a profound change towards patient-centered and outcome-driven healthcare delivery. As the healthcare landscape continues to evolve, embracing VBC offers the prospect of enhancing patient outcomes, improving the patient experience, and promoting cost-effective care. However, to unlock the complete potential of this shift in payment models, it may be necessary to seek guidance from healthcare advisors who possess specialized expertise in this field. These advisors play a vital role in helping address patient population challenges, defining pertinent quality metrics, and aligning incentives effectively. In addition, transactions for entities in the VBC space, or healthcare operators looking to enter the VBC space have a need for a specialized understanding of these relatively novel APM models in terms of valuation, reimbursement dynamics, and related transaction agreements.

Sources

- Abou-Atme, Z., Alterman, R., Khanna, G., & Levine, E. (2022, December 16). Investing in the new era of value-based care. McKinsey & Company.

- Mehta, K., & Ferson, M. (2021, November 2). Value Transformation in Specialty Care. HealthScape Advisors.

- Fowler, L., Rawal, P., Fogler, S., Waldersen, B., O’Connell, M., & Quinton, J. (2022, November 2). The CMS Innovation Center’s Strategy to Support Person-centered, Value-based Specialty Care. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

- King, R. (2022, May 12). CMMI plots ways to grow specialty providers’ role in value-based care. Fierce Healthcare.

- Fry, S., Nierenberg, D., Wynn, G., Murphy, K., & Jain, N. (2023, April 10). Value-Based Care: Opportunities Explained. Bain & Company.

- Gates, K. (2023, August 2). ROI on Annual Health Check-ups? LinkedIn.

- Advisory Board. (2023). Shifting the balance of VBC in Medicare Advantage.

- Fish, M., & Van Ert, M. (2023, June 30). Value-Based Care: Operational Context Matters. FTI Consulting.

- Ochieng, N., Biniek, J. F., Freed, M., Damico, A., & Neuman, T. (2023, August 9). Medicare Advantage in 2023: Enrollment Update and Key Trends. KFF.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. (2022, September 29). Medicare Advantage Value-Based Insurance Design Model Calendar Year 2023 Model Participation.

- Springer, R. (2023, April 26). Value-Based Care: An Investor’s Guide. PitchBook Data, Inc.

- LaPointe, J. (2016, September 9). Understanding the Value-Based Reimbursement Model Landscape. RevCycleIntelligence.

Categories: Uncategorized

Q3 2022 Snapshot: A Look Inside the Earnings Calls of Public Healthcare Operators

December 15, 2022

By: Madi Whyde, Savanna Ganyard, CFA, Jordan Tussy, and Madison Higgins

VMG Health reviewed the earnings calls of publicly traded healthcare operators that reported earnings for the third quarter that ended on September 30, 2022. By focusing on the major players in select subsectors defined below, we analyzed the frequency of certain keywords including inflation, COVID-19, interest rates, premium labor, and others. We used these keywords to identify which topics commanded the room this earnings season. Highlights from the calls are summarized in this article.

Companies Reviewed:

- Acute Care Hospitals: Community Health Systems, Inc. (CYH), HCA Healthcare, Inc. (HCA), Tenet Healthcare Corporation (THC), Universal Health Services, Inc. (UHS)

- Ambulatory Surgery Centers: Surgery Partners, Inc. (SRGY)

- Diagnostic Imaging: RadNet, Inc. (RDNT)

- Dialysis: DaVita Inc. (DVA)

- Diversified Managed Care: Humana Inc. (HUM), UnitedHealth Group Incorporated (UNH)

- Laboratory: Quest Diagnostics Incorporated (DGX)

- Physician Services and Other: U.S. Physical Therapy, Inc. (USPH)

- Post-Acute: Acadia Healthcare Company, Inc. (ACHC), Amedisys, Inc. (AMED), Chemed Corporation (CHE), Enhabit, Inc. (EHAB), Encompass Health Corporation (EHC), Select Medical Holdings Corporation (SEM)

- Risk-Bearing Organizations: Agilon Health, Inc. (AGL), CareMax, Inc. (CMAX), Privia Health Group, Inc. (PRVA), The Oncology Institute, Inc. (TOI)

Key Takeaway: Volume

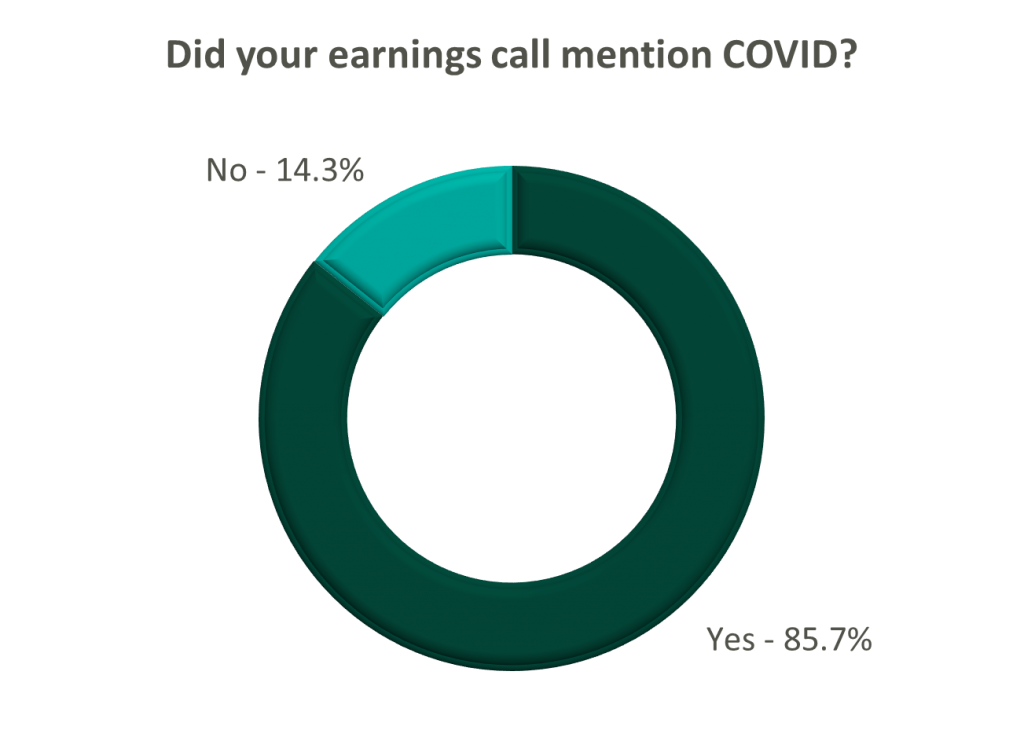

Volume: Although volume trends are unique to each industry sector nearly all operators remained focused on the impacts of COVID.

Poll: Did the earnings call mention COVID-19?

Acute Care Hospitals

On a same-facility basis, admission volumes declined as much as 5.0% from the comparable prior year quarter (Q3 2021) for acute care hospital operators. Despite the weakening of COVID-19, the decline in volumes was attributed to higher-than-average cancellation rates (THC), the migration of certain procedures to outpatient status (CYH and HCA), and capacity constraints (HCA). Inpatient volumes generally remained at or below pre-pandemic levels.

Ambulatory Surgery Centers

Ambulatory surgery center (ASC) operators reaped the benefits of the migration to the outpatient setting and reported positive volume trends when compared to Q3 2021. Surgical volumes were reported as consistent with 2019 pre-pandemic levels (THC), and one operator claimed the business did not experience any material direct impact related to COVID-19 during Q3 2022 (SGRY).

Post-Acute

The post-acute sector reported mixed results in volume trends. One operator reported a year-over-year decline of 14.0% in hospice admissions, citing capacity constraints and reduced referrals from acute care hospitals (EHAB). However, another operator indicated that increases in admissions in the second half of the third quarter showed growth that they “haven’t experienced since the start of the pandemic” (CHE).

All Other

Volume trends among other industry players including dialysis providers, risk-bearing organizations, and physician services were also affected by COVID-19 in Q3 2022. Headwinds in dialysis volumes are expected to persist for the foreseeable future (DVA), and inpatient volumes for risk-bearing organizations remain below pre-pandemic levels (AGL). Notably, AGL also reported a rebound in physician office visits and outpatient volumes were in line with pre-pandemic levels.

Key Takeaway: Reimbursement

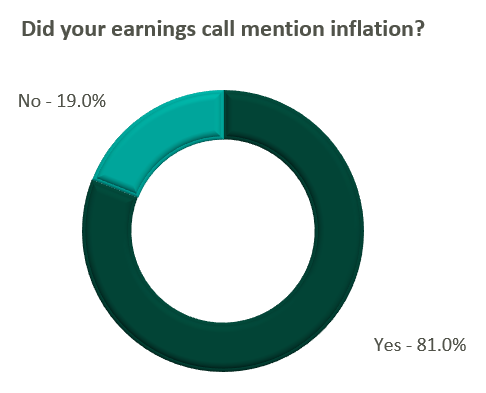

Reimbursement: Declining COVID-19 volumes mean less incremental government revenue for certain industry players who also now contend with an uncertain inflationary environment.

Poll: Did the earnings call mention inflation?

Acute Care Hospitals

Declining COVID-19 volumes resulted in lower acuity patients and reduced incremental government reimbursement. This softened the reimbursement per admission for the acute care hospital segment. Further exacerbated by inflation, these dynamics were evident in reported EBITDA margins which declined as much as 17.0% (CYH) over Q3 2021. In response, some acute care hospital operators are turning to commercial payor negotiations. Rate increases for the next year are anticipated to range from a minimum of 3.0% (THC) to upwards of 6.0% (CYH).

Post-Acute

The post-acute sector did not release specific figures regarding contract rate hikes. However, the sector is optimistically looking for high single-digit rate increases (SEM) to provide relief in the current inflationary environment.

Key Takeaway: Labor

Labor: Unsurprisingly, management teams across the sector were faced with questions about labor trends and management techniques during their earnings calls. Contract labor remained pivotal for the operations of some, but premium labor appears to have softened during the quarter.

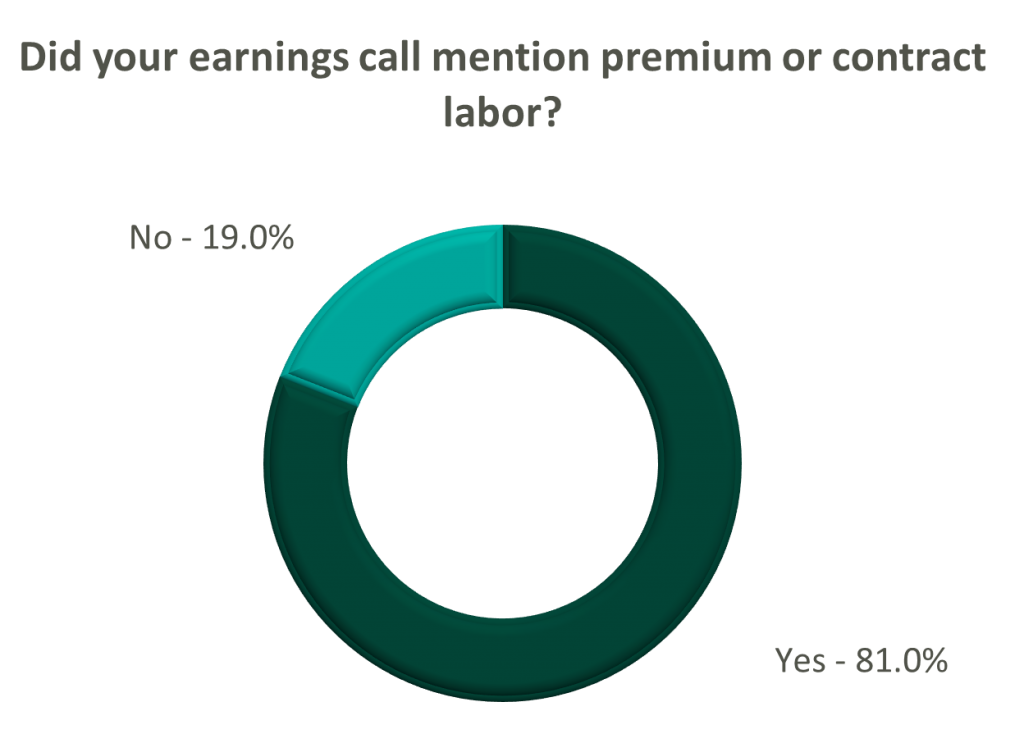

Poll: Did the earnings call mention premium or contract labor?

Acute Care Hospitals

The reliance on contract labor continued its downward trend in Q3 helping moderate expenses. HCA even indicated overall labor costs were stable due to targeted market adjustments. However, contract labor and premium pay remain at uncomfortably high levels for most acute care hospital operators. UHS revealed during their call it will be unlikely to reach pre-pandemic levels in the near future.

Post-Acute

Staffing challenges persisted among the post-acute operators and directly impacted volume by as much as 60.0% (AMED). Increased indirect labor costs including orientation, training, and sign-on bonuses were the leading drivers of decreased EBITDA (AMED). Wage inflation, particularly for nursing positions, is expected to rise as much as 5.0% next year (SEM). However, several management teams are optimistic wages will stabilize to historical levels (SEM, EHC) in the near future.

All Other

Other industry players, including dialysis and physical therapy providers, also faced challenges with contract labor during the quarter. USPH reported labor costs were approximately 200 basis points higher than Q3 2021 levels, and DVA indicated such costs showed no improvement.

Key Takeaway: Go Forward Expectations and Guidance

Go Forward Expectations and Guidance: Considering the quarter’s performance, the companies we reviewed were divided relatively evenly in terms of revised FY 2022 revenue guidance, (i.e., raised, lowered, unchanged). In general, the quarter brought about a more pessimistic view of FY 2022 EBITDA, and the majority of public companies lowered their guidance for the year. Further, most stakeholders were left with no guidance for FY 2023.

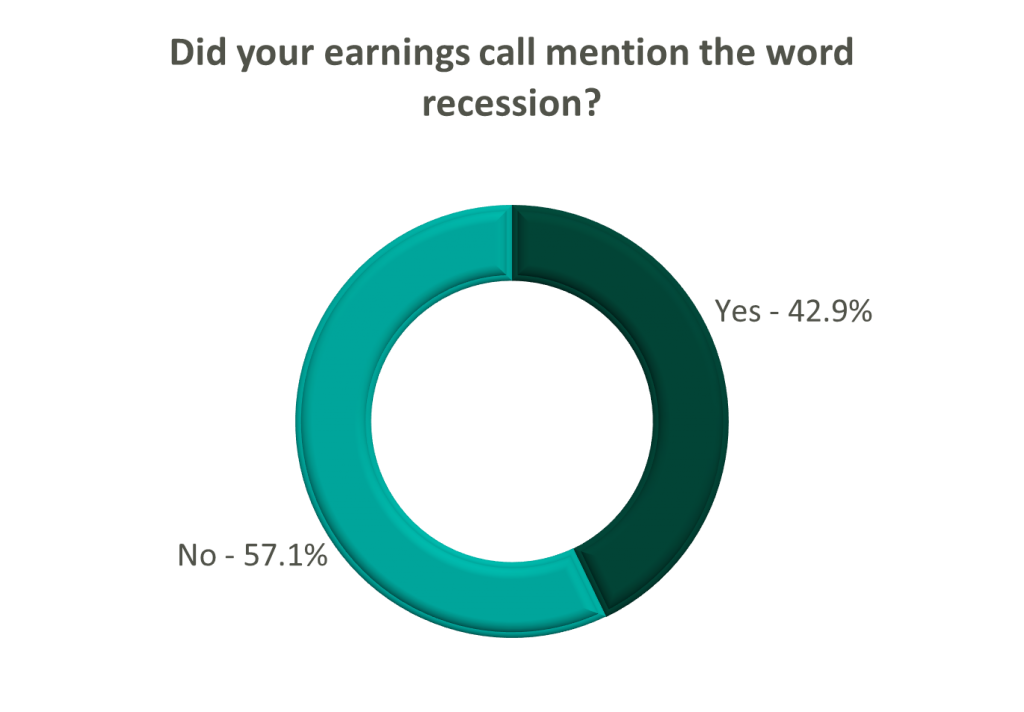

Poll: Did the earnings call mention a recession?

Acute Care Hospitals

FY 2022 revenue and EBITDA guidance among the acute care hospital operators was generally left unchanged except for THC which lowered EBITDA guidance. However, all companies that were reviewed declined to provide FY 2023 guidance during the call, and primarily cited economic uncertainty (HCA).

Post-Acute

The post-acute sector appeared nearly unanimous in the outlook for the rest of 2022, and most operators lowered their revenue and EBITDA guidance. Unsurprisingly, no one offered FY 2023 guidance during the earnings calls.

Risk-Bearing Organizations

Interestingly, risk-bearing organizations mostly raised their revenue guidance for FY 2022 (AGL, CMAX, PRVA). However, EBITDA guidance was less predictable and was lowered (AGL, TOI), raised (PRVA), and unchanged (CMAX).

All Other

Most other healthcare operators followed similar patterns in terms of providing guidance for FY 2023. Of the companies we reviewed, only DVA revealed an outlook for the next year. The company anticipates revenue to be flat (driven by unfavorable volume trends) and margins to continue to feel the impact of labor market pressures.

Categories: Uncategorized

The Evolution and Future Outlook of PACE Programs following the COVID 19 Pandemic

August 18, 2021

Written by Tyler Perper, Kevin McDonough, CFA & Chloe White

The impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic have been felt throughout the healthcare industry and led to major shifts across all verticals. In particular, the care of the elderly and frail population has faced some of the most scrutiny over the past 18 months given the population’s elevated level of susceptibility to Covid-19 and the major safety protocols that come along with keeping them protected from transmission. Institutional, in-home, and community-based long-term services and support (“LTTS”) providers were forced to make major changes in procedure and delivery of care which has led to mixed results. However, one segment of the LTTS healthcare sector, Programs of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly, or “PACE” organizations, has been incredibly successful in evolving its services under the tumultuous circumstances of the pandemic. The pandemic provided a unique opportunity for PACE organizations to rethink in-community and care-based services for participants. Throughout the pandemic, PACE organizations consistently demonstrated the ability to pivot quickly and effectively while maintaining a high level of safety for their enrollees and staff; all the while, keeping the cost of care under control.

PACE Programs are community-based programs serving over 55,000 elderly participants across 31 states and D.C. (1). Under PACE, enrollees are provided with an extensive list of care and services covered by Medicare and Medicaid as well as necessary care and services not covered while still able to reside in their own home (2). The general eligibility of PACE programs requires the enrollee to be above 55 years, reside in the PACE organization’s service area, and be certified as eligible for nursing home care by their state while able to live in a community setting (2).

PACE Programs, as opposed to other long-term care-facilities, allow enrollees to live in their own homes while providing transportation to the on-site PACE community center, with a central objective of reducing cost of care and admissions to both hospitals and residential care facilities (3). The platform allows for socialization and interaction but does not require nor offer 24/7 contact with other enrollees and staff. This degree of separation of enrollees largely affected the number of transmissions of Covid and Covid-related deaths in PACE Programs; approximately 1.39% of PACE enrollees tested positive and died from Covid-19 as of July 27, 2020 whereas 5.23% of the 1.3 million nursing home residents had died from Covid-19 as of August 13, 2020 (4). Despite enrollees’ frailty and eligibility for nursing homes, PACE participants, on average, had fewer hospitalizations, less time in the hospital, and a lower death rate than nursing home residents for both Covid and non-Covid related ailments (4). Non-communal living allowed PACE Programs the ability to change course rapidly without the concern of transmission from member to member or staff to member.

When the pandemic first began, PACE programs had to pivot, and could no longer view themselves as solely a physical location, but rather a moving entity comprised of enrollees, staff, and transportation vans. Problems centered around the conglomeration of people to receive care and to interact socially within the PACE centers (3). PACE programs had to redesign their care model almost overnight to accommodate regulations and to protect enrollees. All activities ceased, care providers were sent into homes, transportation vans became mobile health clinics, daily phone calls were made to enrollees, meals were delivered to homes, and activities became virtual (3). While every precaution taken was to protect enrollees, with the reduced interaction, loneliness for enrollees living alone became a pervasive issue. To combat this issue, some PACE programs partnered with telehealth companies. One PACE Program, Element Care, partnered with the telehealth company GrandPad, to obtain a proprietary tablet with a simple interface which allowed their enrollees to reach nurses, complete physical therapy, and participate in social activities (5). This program was one of many that were able to effectively reduce levels of loneliness and depression with the implementation of telehealth that offered enrollees an alternative way to connect with their peers during periods of isolation.

A huge concern surrounding care for the enrollees was the temporary closure of medical practices, due to the pandemic, to assist with the enrollees’ average six chronic illnesses (4). As a potential solution, Summit Eldercare, one of the largest PACE programs, opted to transform their in-house community center into an infirmary to care for Covid-positive members who were discharged from hospitals (4). It took about a month for Summit Eldercare to get the infirmary running, serving a total of 11 patients and providing around-the-clock care (4). Although the last patient was discharged in June of 2020, Summit Eldercare demonstrated PACE programs’ ability to utilize space effectively with the resources at their disposal.

PACE offers a much more dynamic and evolving system of aging that gained popularity and traction with the loosening of legal boundaries and allowance of for-profit entities entry into the market in 2015 (7). Prior to 2015, PACE programs were solely non-profit organizations that were plagued by static growth in participants and locations around the country despite the high demand for eldercare services (1). By 2030, the youngest Baby Boomers will be above the age of 65, contributing to the overall aging of the US population and creating a strain on the healthcare system (8). PACE has the opportunity to tap into this market and the potential to grow through scale, spread, and scope; increasing the number of people, number of organizations and communities served, and expanding the range of populations that PACE serves (9).

PACE Programs demonstrated the adaptive nature of the platform and their potential for growth, however, PACE still have substantial issues as the nation emerges from lockdown. Job growth in the leisure and hospitality industry has grown significantly over the past three months and Healthcare is one of the industries with the highest amount of job openings, in part due to 2/3rds of workers who lost their jobs either reconsidering their job choice or choosing to stay home (10). As PACE organizations plan for future expansion, these organizations will be forced to navigate a tight labor market in order to provide the full spectrum of care to new participants.

PACE programs adapted to the “new normal” that COVID presented and proved the benefits for quality in home and community-based care. Given the successes of PACE since the spring of 2020, policymakers around the country will continue to take notice and deliberate further expansion of the programs in their states. Although PACE has its fair share of headwinds, the innovative mindset of the operators as well as the program’s track record during the pandemic bodes well for the future of PACE in the ever-growing elderly care market space.

Sources:

- https://www.pacenation.org/pace-programs/

- https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Downloads/pace111c01.pdf

- https://www.bettercareplaybook.org/_blog/2020/19/pace-response-covid-19-calls-policy-actions-increasing-access-and-affordability

- https://www.ipfcc.org/resources/Altarum_Program-to-Improve-Eldercare_Rapid-PACE-Responses_report.pdf

- https://www.hcinnovationgroup.com/population-health-management/complex-care/article/21229296/pace-programs-continue-to-innovate?fbclid=IwAR2RBdxOImuPFo5T-b8HKGnw0EFjkFORxmYgwNPkFp2F-CDDMZI2XP-I9Xk

- https://nam.edu/reimagining-nursing-homes-in-the-wake-of-covid-19/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2690172/

- https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/12/by-2030-all-baby-boomers-will-be-age-65-or-older.html

- https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/oct/expanding-pace-model-high-need-high-cost

- https://www.govtech.com/education/higher-ed/states-expand-apprenticeship-programs-as-worker-shortages-grow

Categories: Uncategorized

Industry Expert

Exploring the World of Value-Based Care: An Overview

Written by Tyler Perper and Matthew Marconcini, CPA The following article was published by Becker’s Hospital Review. The landscape of...

Learn More