- About Us

- Our Clients

- Services

- Insights

- Healthcare Sectors

- Ambulatory Surgery Centers

- Behavioral Health

- Dialysis

- Hospital-Based Medicine

- Hospitals

- Imaging & Radiology

- Laboratories

- Medical Device & Life Sciences

- Medical Transport

- Oncology

- Pharmacy

- Physician Practices

- Post-Acute Care

- Risk-Bearing Organizations & Health Plans

- Telehealth & Healthcare IT

- Urgent Care & Free Standing EDs

- Careers

- Contact Us

Built-to-Suit: Constructing a New Building? Transaction Structuring, FMV, and Compliance Considerations – Part 2: Credit Ratings and BTS Healthcare Assets

June 22, 2021

By: Victor McConnell, MAI, ASA, CRE, Frank Fehribach, MAI, MRICS, and Grace McWatters

*This is Part 2 in VMG’s series on transaction structuring considerations for new developments. The other parts in this series can be found here: Part 1, Part 3, Part 4.

Are you constructing a new building, on or off of a hospital campus? If so, there are unique considerations that investors, JV partners, developers, hospitals, physicians, and other parties to a new development should evaluate. For instance, if a hospital and/or a physician partner are developing a building and then leasing it to a JV entity, the associated lease rate and overall development terms will likely need to be documented as being commercially reasonable [1] and within fair market value (“FMV”) parameters. For investors constructing build-to-suits, primary concerns may revolve around analyzing the risk associated with a particular tenant. For hospitals and physician partners who are joint venturing on a development, the key analyses may involve appropriate allocation of risk, responsibility, and capital vs. non-capital contributions that each party is making to the development. If parties are sharing in development responsibility and risk, then a careful analysis should be undertaken to ensure that parties receive appropriate return given their risk, as well as their various capital and non-capital contributions.

This article will provide an overview of key issues to be considered prior to, during, and subsequent to construction of a new building. For assistance with transaction advisory, cost benchmarking, FMV analysis, commercial reasonableness opinions, or other consulting services, please contact VMG Health.

In Part 1, we covered the economics of build-to-suit projects, the rates and returns associated with their development, as well as the types of costs and fees that can be expected during various stages of these projects. Part 2, which is presented below, will cover variance in credit ratings, lease quality, and tenant risk and how these factors can influence the profitability of a project. Parts 3 and 4 will be presented separately and will cover the relationship between capital markets and BTS rates, as well as rent factors and amortization rates, and how these factors impact development terms.

Credit Ratings and Their Impact on Build-to-Suit Deals

The terms that a landlord/developer will offer a tenant in a build-to-suit scenario are affected by the tenant’s credit rating. Some build-to-suit projects include lease guarantees from parent entities (hospital systems, platform companies, etc), while others are guaranteed by a facility-specific LLC or a physician group. A credit guaranty may be a non-capital contribution to a development that should be taken into account in a JV structure (or in setting the RoC rate with the developer). In the event that a JV develops a new building, but development responsibilities and capital (or non-capital) contributions vary between the parties, then adjustments may be required (in terms of ownership percentages versus cost, or in terms of the go-forward project lease rate) to ensure that the deal structure is consistent with FMV and is commercially reasonable.

Credit ratings and tenant risk are complex topics which have been analyzed extensively within the commercial real estate sector. A “credit tenant” is defined differently by different sources. One definition is as follows: “A tenant in a retail, office, or commercial property with a long history in business, strong financial statements, or a large market presence that could be rated as investment grade by a rating agency. Because of the likelihood of honoring their leases, credit tenants are considered less risky to lease to, and developments with credit tenants as anchors are considered less risky investments for lenders.” [2]

It is worth noting that the preceding definition defines a “credit tenant” as not strictly limited to an entity with a credit rating, though some market participants do define it as such. For instance, a research paper by Sonneman and Yerke published in The Counselors of Real Estate in 2013 defined a credit tenant as “one whose bond issues fall within the investment grade levels set by one of the three major rating agencies.” [3] However, the article also defines an ideal single-tenant, investment grade lease as: being long-term with no early termination, a triple-net or absolute net structure, periodic rent increases, and featuring multiple renewal periods.

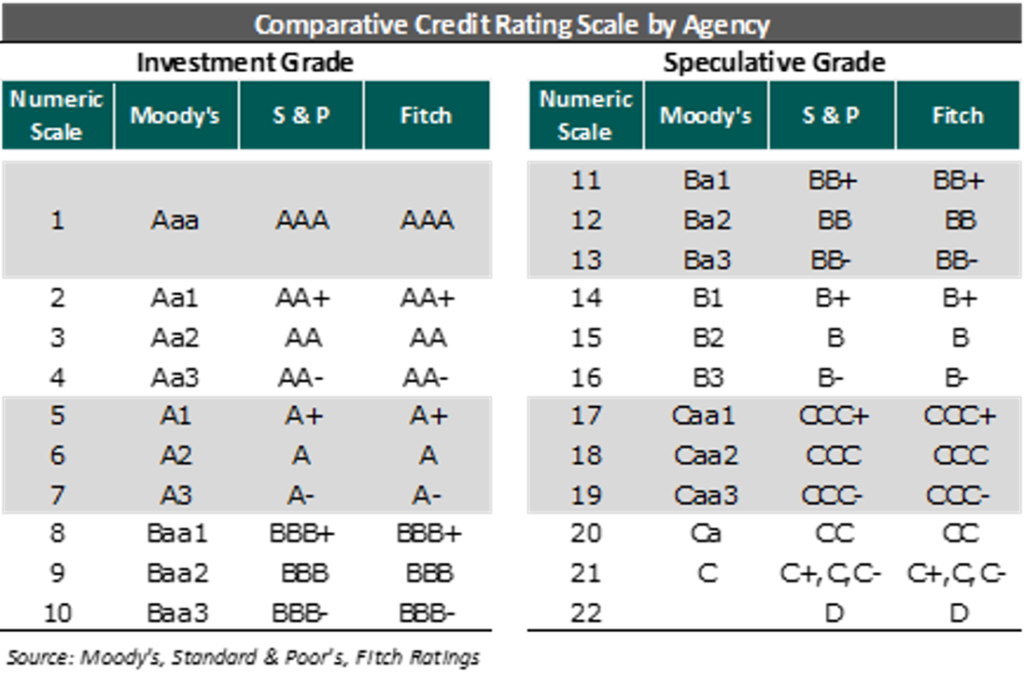

The accompanying chart (“Comparative Credit Rating Scale by Agency”) provides comparison of the credit ratings for the three main credit rating agencies: Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (“S&P”), and Fitch Ratings.

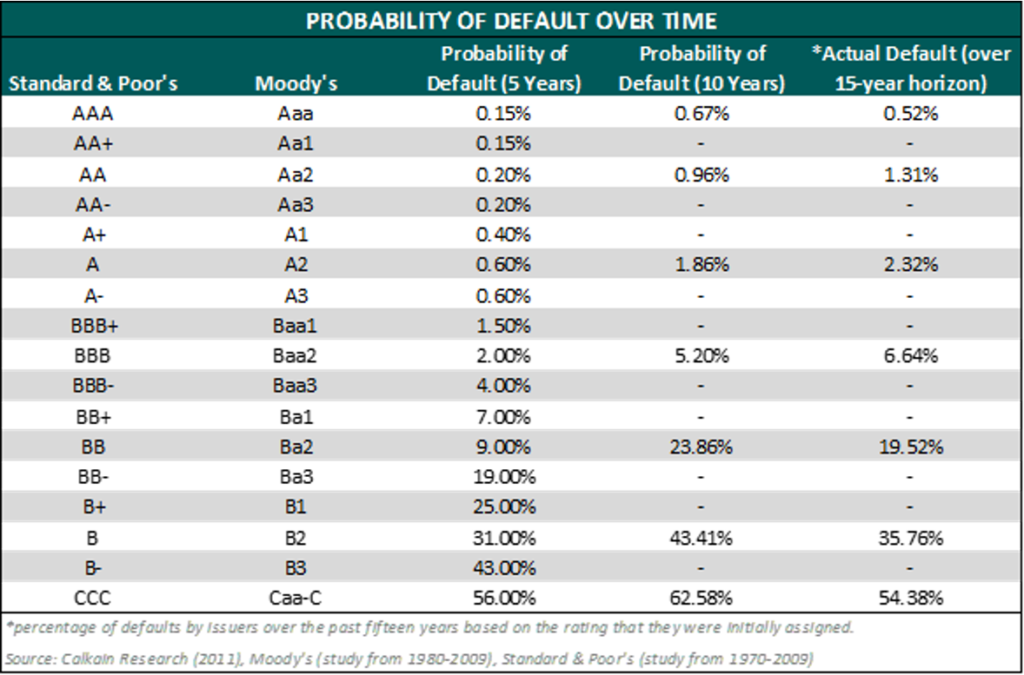

The ratings agencies have periodically evaluated their ratings relative to actual default rates and have assigned default probabilities for each rating, as summarized in the accompanying table (“Probability of Default Over Time”).

Calkain, a boutique commercial real estate firm focused in the net lease market, has a research arm which provides extensive market commentary within the net lease sector and has published numerous surveys and white papers. In a 2011 study of credit ratings and cap rates, Calkain noted that “Moody’s also measured default rates from 1970-2009 based on a company’s issued rating. At 5, 10, and 20 years, investment grade companies’ likelihood of defaulting were .973%, 2.503%, and 6.661% respectively. On the other hand, speculative grade companies over the same time horizons were 21.359%, 34.005%, and 49.649%, respectively.” [4] Entities with inferior credit ratings not only tend to default at a greater overall rate over a long period, but they also default more quickly when starting from a given point in time. For instance, Calkain’s paper also stated that “According to a study done by S&P from 1981-2009, the lower the credit rating, the faster the time of default. For example, the AAA rated companies that defaulted did so on average at 16 years from the issuance of rating, BBB and CCC rated companies did so at 7.5 and 0.9 years respectively. This shows that not only do lower rated companies have a higher probability of default, but [default] also happens at an accelerated pace with lower rating.” Within the context of the single-tenant, net-lease sector, a default likely equates to the early termination of a lease. The consequences of early lease termination depend on the lease rate relative to market as well as the risks and costs related to re-tenanting the property. Real estate investors in the single-tenant net lease sector must evaluate these considerations in their acquisition decisions. For a single-tenant, net-leased specialty asset, the cost of re-tenanting the property can be significant. In a build-to-suit scenario, a developer, lender, or investor must carefully evaluate potential downside risk scenarios in determining an appropriate RoC rate.

A paper titled “Net-Leased Single-Tenant Risks” published by George Renz in the November – December 2014 CCIM Institute publication attempted to address the question of the likelihood of a tenant actually paying rent over a 10-20+ year time horizon. [5] The paper stated that “an analysis of 100 NLST [net-lease single-tenant] deals answers the question. Out of 100 transactions with locations nationwide ranging in value from $322,000 to $9 million, only six tenants filed bankruptcy or did not pay rent. The breakdown: 1) of 70 investment-grade and national tenants, no investment grade tenants defaulted and only one national tenant defaulted; 2) of 30 franchisee, regional, and local tenants, five defaulted.” The paper provided minimal detail regarding the 100-transaction sample, and thus extrapolating any broad default probabilities would be difficult. That said, the article serves as another example of the general commercial real estate investment community’s continued attempt to evaluate risk within the single-tenant net lease sector; the activities of these market participants ultimately affect investment decisions (and, correspondingly, cap rate trends).

Other researchers have analyzed real estate lease backed securities in evaluating risk. McMurray and Mundel noted in a 1997 academic study that “for risky lessees, i.e. all lessees where there is a possibility of default in some period t < T, a credit spread must be added to the risk-free discount rate, r, in the equations shown previously.” [6] The paper noted significant risk factors impacting normative lease credit spreads including lease maturity, mean reversion, correlation, and volatility.

The purpose of discussing real estate backed securities relative to an examination of the build-to-suit healthcare real estate market is to illustrate the expansion of the buyer pool which occurs when a property features a lease backed by a credit-worthy corporate entity; properties which lack credit rated tenants could not be included within an investment grade real estate lease backed security, thus eliminating a portion of the buyer pool (institutional buyers that only invested in highly rated securities; significantly, this portion of the buyer pool typically has a lower cost of capital). If the combination of real estate, lease quality, and tenant quality is sufficient to attract institutional buyers, an impact on the property’s value (i.e. cap rate) would be expected.

In some cases with a specialty built healthcare asset (particularly on a hospital campus), the ability of a developer/landlord to sell may be subject to certain restrictions. However, even absent a sale, the risk profile associated with the lease income stream affects the debt terms achievable in the capital markets; while debt issuance is different than the sale of a property, the terms of the debt ultimately affect the developer/landlord’s profitability.

The previously referenced 2011 Calkain study noted “each lender has different criteria for who they lend to. For example, CTL [Credit Tenant Lease financing] lenders will only lend to investment tenants regardless of real estate. On the other hand, insurance companies such as American Fidelity assess all types of companies and measure them through H and Z scores to determine if they qualify. […] On [American Fidelity’s] list of approved retail credits, there were 71 retailers they would lend to and 55 not approved.” This excerpt illustrates another issue which can cause cap rate compression: superior available financing terms for properties with comparatively lower risk profiles. If a buyer can access financing at a lower rate, then it follows that the buyer would be willing to acquire the property at a lower cap rate, as the spread between the cap rate and the financing represents an arbitrage opportunity.

VMG has previously performed extensive research into the impact of credit guarantees on a variety of outpatient and inpatient healthcare assets. The impact of a credit tenant is more significant, generally, when the underlying real estate is less valuable. When the underlying real estate features strong fundamentals (i.e. growing demographic trends, high land values, strong occupancy rates, increasing rent rates, and so forth), then the impact of a credit guarantee may be diminished.

For further information concerning quantifying the value of a lease guaranty, please contact VMG Health.

The next section (Part 3) in this Build-to-Suit series involves further discussion of build-to-suits and capital markets.

Footnotes & Sources:

[1] In the December 2, 2020 Final Rule, CMS provided updated and detailed guidance on commercial reasonableness (“CR”). CR is a complex topic and a detailed CR discussion is beyond the scope of this article. For questions regarding commercial reasonableness in the context of a new real estate development, please contact VMG Health.

[2] The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 6th Edition (Chicago: Appraisal Institute, 2015).

[3] Sonneman, Donald, et al. “Comparing Value: U.S. Government Office Leases vs. Credit Tenant Leases.” The Counselors of Real Estate, Spring 2013, Vol. 38, Number 1, pp. 20-30.

[4] Caswell, Chris. “Credit Rating Effect on the Marketplace” Calkain Research, reviewed by David Sobelman, Stanley Wyricz, Richard Murphy, Michael O’Mara, Orzechowski, Winston. 2015, pp. 1-15.

[5] Renz, George L. “Net-Leased Single-Tenant Risks.” CCIM Institute, November│December 2014, pp. 22-25.

[6] McMurray, John P., Samuel M. Mundel. “Real Estate Lease-Backed Securities.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, September 1997, pp. 1-84.

Categories: Uncategorized

Subscribe

to our blog