- About Us

- Our Clients

- Services

- Insights

- Healthcare Sectors

- Ambulatory Surgery Centers

- Behavioral Health

- Dialysis

- Hospital-Based Medicine

- Hospitals

- Imaging & Radiology

- Laboratories

- Medical Device & Life Sciences

- Medical Transport

- Oncology

- Pharmacy

- Physician Practices

- Post-Acute Care

- Risk-Bearing Organizations & Health Plans

- Telehealth & Healthcare IT

- Urgent Care & Free Standing EDs

- Careers

- Contact Us

Built-to-Suit: Constructing a New Building? Transaction Structuring, FMV, and Compliance Considerations – Part 4: Conclusion and Additional Resources

June 28, 2021

By: Victor McConnell, MAI, ASA, CRE, Frank Fehribach, MAI, MRICS, and Grace McWatters

*This is Part 4 in VMG’s series on transaction structuring considerations for new developments. The other parts in this series can be found here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3.

This four-part series has provided an overview of the unique considerations that investors, JV partners, developers, hospitals, physicians, and other parties to a new development should evaluate in pursuing a new project. For instance, if a hospital and/or a physician partner are developing a building and then leasing it to a JV entity, the associated lease rate and overall development terms will likely need to be documented as being commercially reasonable[1] and within fair market value (“FMV”) parameters. For investors constructing build-to-suits, primary concerns may revolve around analyzing the risk associated with a particular tenant. For hospitals and physician partners who are joint venturing on a development, the key analyses may involve appropriate allocation of risk, responsibility, and capital vs. non-capital contributions that each party is making to the development. If parties are sharing in development responsibility and risk, then a careful analysis should be undertaken to ensure that parties receive appropriate return given their risk, as well as their various capital and non-capital contributions.

If you are evaluating a new project and require outside assistance, VMG Health is well-equipped to assist with the following:

- FMV lease rate analysis

- Transaction advisory regarding capital and non-capital contributions

- Initial yield on cost analysis

- Construction cost benchmarking

- Residual value projections

- Replacement cost / insurable value estimates

- Purchase option, right of first offer/first refusal analysis

- Commercial reasonableness analysis

- Transaction advisory regarding lease structure

- Ground lease rent analysis

Finally, as is evidenced by the overview presented within this series, transaction and valuation considerations associated with new construction are complex. VMG has previously published thought leadership focused on a number of areas which are pertinent when evaluating new construction. These include: a) insurable value/replacement cost; b) on- v. off-campus locations; c) ground leases on hospital campuses; d) MOB financial feasibility; e) specialty assets; and f) premium sites (i.e. healthcare projects with high land values). The final section of this series will include more specific examination of each of these individual topics. For further guidance on these topics, please refer to the following resources.

Other Guidance and Considerations Pertinent to New Construction

Insurable Value / Replacement Cost – Another item to evaluate prior to (and subsequent to) a new development is insurable value and replacement cost. For more on this topic, please refer to VMG’s published guidance here:

On v. Off-Campus Location – Whether the new project is situated on or off a hospital campus can have a significant impact. Use restrictions, different reimbursement status, ground lease issues, and other factors could all affect the project’s success (and associated development risk). Furthermore, certain real estate fundamentals (related to rent rates, cap rates, and sale prices) also are affected by on- vs. off-campus locations. For more on this topic, please refer to VMG’s published guidance here*:

On-campus Medical Office Buildings: Is a Premium Warranted? If So, When and Why?

*Please note that this article was published in December 2016. Stark Law FMV definition and market conditions have changed in the intervening years; please contact VMG with questions related to how these changes may affect the commentary and analysis in this article.

Ground Lease Considerations – If the proposed development is to be situated on a ground-leased site, a variety of transaction structuring issues must be navigated, along with variance in risk profile and associated market-based return. For further guidance on ground lease considerations associated with hospital campuses, please refer to the following:

Under All is the Land: Ground Leases and Hospital Campuses

Financial Feasibility – In some cases, a building may not be 100% master leased. A hospital or a developer may construct a building with the intent to go “at risk” for a certain amount of space. Risk considerations associated with that development could then include evaluating various real estate market fundamentals, including lease-up period, area payor mix, patient drive-times, demand for various physician specialties, and so forth. For more on this topic, please refer to VMG’s published guidance here:

Financial Feasibility & Speculative Medical Office Building Construction

Specialty Assets – Some build-to-suit projects involve highly specialized real estate assets. Further diligence related to the particular health vertical (ASC, imaging, radiation oncology, specialty hospital, etc.) may be required in this case. Examples of highly specialized sectors on which VMG has published real estate related guidance include life sciences and micro-hospitals. For more, see the below:

Micro-Hospital Real Estate: Six Key Considerations

Spotlight on Life Sciences – Healthcare Real Estate

Premium Sites – Site value affects the “all-in” development cost, and accordingly can affect rental rates in a built-to-suit scenario (or feasibility in a speculative development). Sites located in dense, urban environments have unique considerations which drive pricing. See the following article for VMG’s commentary on considerations related to premium site locations:

Location, Location, Location: Premium Sites and Healthcare Real Estate

For any questions concerning a new or proposed development, please contact VMG Health’s real estate department.

Footnotes:

[1] In the December 2, 2020 Final Rule, CMS provided updated and detailed guidance on commercial reasonableness (“CR”). CR is a complex topic, and a detailed CR discussion is beyond the scope of this article. For questions regarding commercial reasonableness in the context of a new real estate development, please contact VMG Health.

Categories: Uncategorized

Built-to-Suit: Constructing a New Building? Transaction Structuring, FMV, and Compliance Considerations – Part 3: Build-to-Suits and Capital Markets

June 28, 2021

By: Victor McConnell, MAI, ASA, CRE, Frank Fehribach, MAI, MRICS, and Grace McWatters

*This is Part 3 in VMG’s series on transaction structuring considerations for new developments. The other parts in this series can be found here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 4.

Are you constructing a new building, on or off of a hospital campus? If so, there are unique considerations that investors, JV partners, developers, hospitals, physicians, and other parties to a new development should evaluate. For instance, if a hospital and/or a physician partner are developing a building and then leasing it to a JV entity, the associated lease rate and overall development terms will likely need to be documented as being commercially reasonable [1] and within fair market value (“FMV”) parameters. For investors constructing build-to-suits, primary concerns may revolve around analyzing the risk associated with a particular tenant. For hospitals and physician partners who are joint venturing on a development, the key analyses may involve appropriate allocation of risk, responsibility, and capital vs. non-capital contributions that each party is making to the development. If parties are sharing in development responsibility and risk, then a careful analysis should be undertaken to ensure that parties receive appropriate return given their risk, as well as their various capital and non-capital contributions.

This article will provide an overview of key issues to be considered prior to, during, and subsequent to construction of a new building. For assistance with transaction advisory, cost benchmarking, FMV analysis, commercial reasonableness opinions, or other consulting services, please contact VMG Health.

In Part 1, we covered the economics of build-to-suit projects, the rates and returns associated with their development, as well as the types of costs and fees that can be expected during various stages of these projects. In Part 2, we covered variance in credit ratings, lease quality, and tenant risk, and how these factors can influence the profitability of a project. Part 3, which is presented below, will cover the relationship between capital markets and BTS rates, as well as rent factors and amortization rates, and how these factors impact development terms.

Build-to-Suit Rates and Capital Markets

As previously discussed, build-to-suit rates are significantly affected by cap rate trends, among other factors. Prevailing terms for debt also have a significant impact. For instance, in some CTL structures or loan instruments, a landlord may set a rate based upon a fixed number of basis points above an agreed upon index (such as the U.S. Prime Rate or 10-Year Treasury).

An investor may underwrite a real estate investment assuming a certain “spread” between the rate at which they can borrow money as compared to the rate of return that the property will generate. The cost of debt, the length of the loan, and the loan-to-value (“LTV”) are all significant factors for a real estate investor to evaluate relative to the cap rate at which they will acquire a property or the terms they will offer in a build-to-suit or for a tenant improvement allowance. In some cases, a tenant and landlord may negotiate a predetermined rate for TI amortizations, building additions, purchase options, or put options. In these instances, both landlord and tenant will evaluate the terms relative to alternatives (i.e. alternative investment options and alternative borrowing options).

In the last decade, VMG’s valuation & advisory team has worked extensively within the healthcare real estate sector, including on behalf of lenders, REITs, private equity, as well as health systems and physicians. In a recent consulting project, VMG reviewed information from more than 50 prior projects involving specialty healthcare construction. The goal of this internal data review was to generally evaluate prevailing build-to-suit market trends, as well as to analyze specific agreements where a tenant and landlord agreed on a predetermined price for significant capital expenditures on specialty real estate assets. Furthermore, VMG has analyzed select public REIT filings, historical capital market trends, and pertinent publications and surveys from brokerage firms and academic researchers.

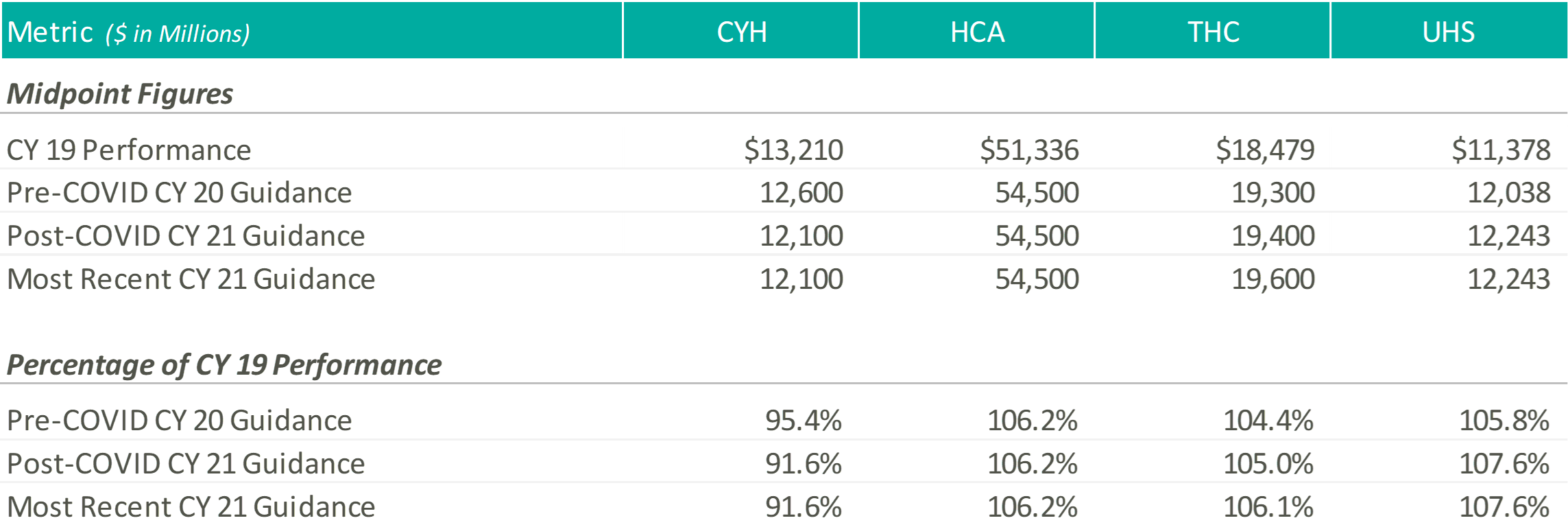

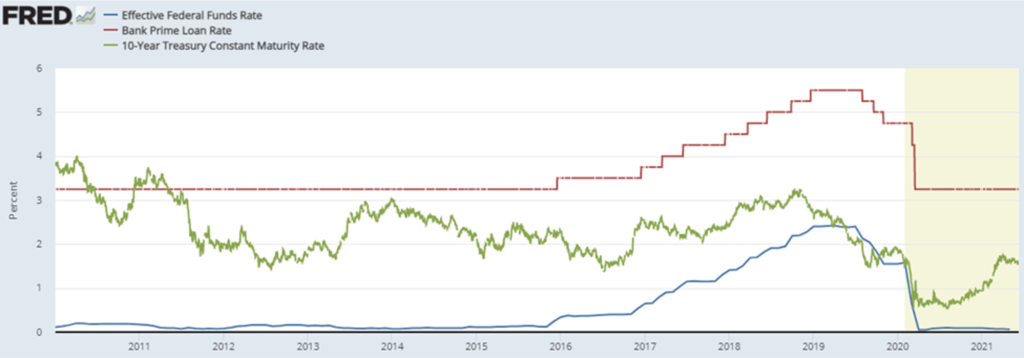

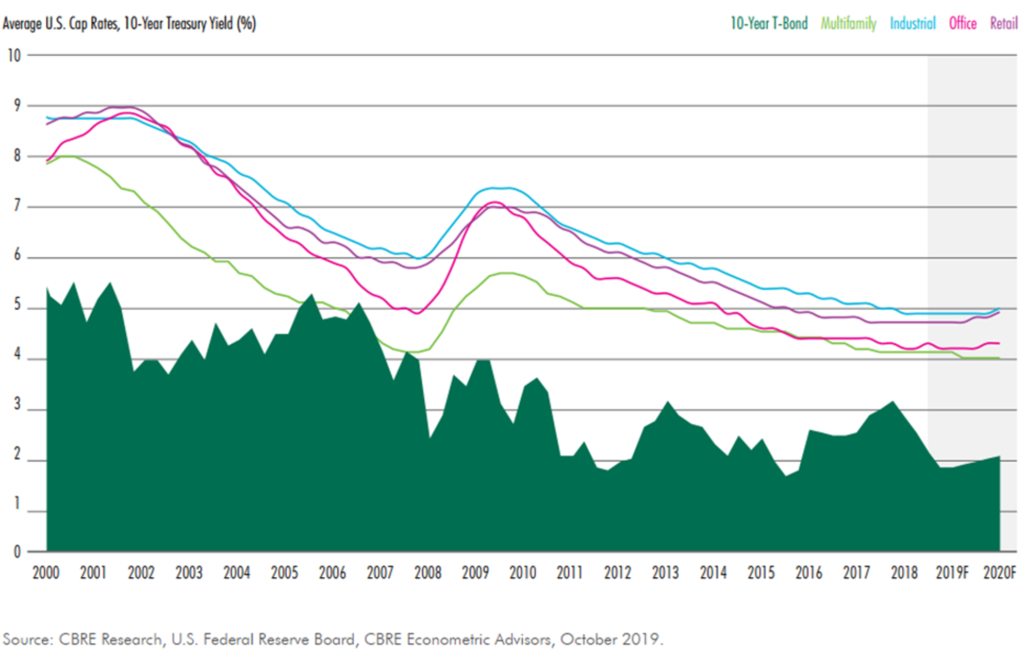

Throughout the commercial real estate sector, prevailing market rates are affected by capital markets conditions, including U.S. Prime Rates (“Prime Rates”). The Prime Rate is generally the lowest rate at which money can be borrowed from commercial banks by non-banks; the Wall Street Journal defines the Prime Rate as “The base rate on corporate loans posted by at least 70% of the 10 largest U.S. banks.” This rate is highly correlated with the Federal Funds Rate. Long-term fixed rates are generally correlated to the 10-Year U.S. Treasury Note (the “10-Year Treasury”). An investor could choose between “locking in” a return on a U.S. Treasury bond (such as the 10-Year Treasury) or investing in the commercial real estate market, where cap rates serve as an indication for an investor’s unlevered return. Unlike a bond with fixed payments, growth in cash flows is anticipated in a real estate investment. Thus, future growth rate assumptions also affect an investor’s overall anticipated return. Examining the spread between the 10-Year Treasury as compared to various commercial real estate (“CRE”) cap rate metrics can reveal changes in investor sentiment, as well as growth expectations. In order to illustrate long-term trends in the capital markets, the following two charts depict the Federal Funds Rate, the 10-Year Treasury Rate, and the U.S. Prime Rate in two periods: since 1950 and since 2010.

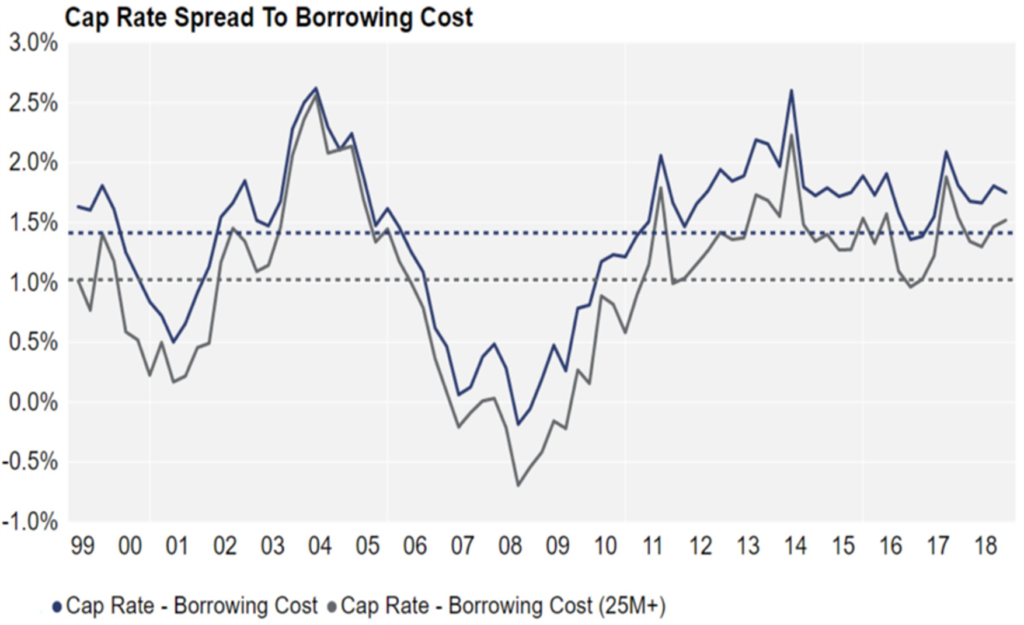

As is evident in the above charts, the three rates are highly correlated, though not perfectly so. These rates also impact the real estate markets, and a variety of research has been performed examining commercial property cap rate trends relative to these rates. The following two charts compare a) core commercial property sectors to the 10-year U.S. Treasury and then b) cap rates as compared to borrowing costs.

Though significant fluctuations are evident, the preceding charts also illustrate general long-term trends related to the spread between the Prime Rate and 10-Year Treasury.

- Between 1990 and 2020, the median spread between the Prime Rate and the 10-Year Treasury was 137 basis points, whereas the 25th and 75th percentile during that period was 42 basis points and 228 basis points.

- Between 1990 and 2020, the median spread between the 10-Year Treasury and the Federal Funds rate was 160 basis points, with a 25th and 75th percentile of 56 and 264 basis points, respectively. Thus, the spread between Prime Rate and Federal Funds rate during this period would be 297 basis points on a median basis.

Prior to the onset of COVID-19 and its impact on the real estate markets, CBRE’s “U.S. Real Estate Market Outlook 2020” noted that “the minimal increase in the 10-Year Treasury yield anticipated for 2020 will help limit cap rate increases and keep the spread about 200 to 300 bps above the risk-free rate next year.” This statement illustrates how institutional real estate investors place real estate returns into context relative to other rate benchmarks, such as the 10-Year Treasury. A study published by Ted. C. Jones, PhD (former chief economist of Texas A&M University’s Real Estate Center) benchmarked commercial real estate cap rates (sourced from Real Capital Analytics) as compared to the 10-Year Treasury on a trailing 12-month (TTM) basis, under the thesis that commercial real estate transactions can take roughly 12 months to close. This study focused on the period from Q1 2001 through Q3 2016. The median spread was 404 basis points, whereas the minimum and maximum were 193 and 509 basis points, respectively. Another study published by Quantum Real Estate Advisors in February 2019 (utilizing slightly different sources and methodology) revealed a general range (between the 10-Year Treasury and CRE cap rates) of 100 to 450 basis points with an average spread of around 300 basis points.

In evaluating a RoC rate for a new development, it should be noted that there is a difference between a rent factor and an amortization rate. By way of illustration, suppose $5,000,000 was provided by a landlord to a tenant for a 10,000-square-foot expansion project ($500/SF). If the landlord and tenant agreed to an 8% rent factor, the rent would be $400,000 per year ($40/SF), e.g. the multiplication of the cost ($5M) by the factor (0.08). However, if landlord and tenant amortized the cost over a 15-year term at 8% (compounded monthly), the annual rent would be $573,391 ($57.34/SF). The same amount amortized over a 25-year term would result in an annual rent of $463,090 ($46.31/SF).

Typically, if a landlord is offering funding based on a rent factor rather than an amortization rate, they are also anticipating residual value at the end of the lease term, or the lease term is long enough that the difference between a rent factor and an amortization rate is minimal. Assuming a 25-year lease term, an amortization rate of 6.75% would result in a similar rent indication as an 8.0% rent constant.

Ultimately, any analysis of a build-to-suit project (or funding of a new addition to an existing hospital campus) should involve careful consideration of and distinction between appropriate amortization rates or rent factors.

Within VMG’s analysis of hundreds of FMV lease rate assessments across the United States, VMG has inquired as to prevailing TI amortization rates for medical office building finish out. The range of TI rates offered by landlords to tenants is affected by capital markets conditions, just as cap rates and other return rates are correlated with various rate benchmarks (such as the 10-Year Treasury). Examples of landlords and tenants agreeing to a formula which predetermines a rate in the future for a lease adjustment or a purchase option are less common, though they do exist. For further discussion of a structure whereby a lease adjustment or purchase option is based on a fixed formula, please contact VMG Health’s real estate division.

Though not always associated with build-to-suits and new construction, the sale/leaseback market also contains pertinent indicators, as well as scenarios which can be somewhat analogous to a build-to-suit. For instance, VMG has reviewed leases executed in sale/leaseback agreements with a REIT whereby the REIT would execute the sale/leaseback at a certain rate and would simultaneously offer to fund certain capital additions at a similar or identical return rate (with this reflected in the lease agreement). Essentially, the REIT was evaluating the risk associated with the tenant/operator as equivalent in two separate scenarios: 1) providing funds in exchange for receipt of the operator’s underlying real estate as collateral (the sale/leaseback) and 2) providing funds for a capital addition to the existing collateral in exchange for the operator’s commitment to lease the capital addition at the same return rate. However, in both cases, in selecting its return rate (whether an amortization rate or rent factor), the REIT is also assessing the likelihood of renewal and the residual value that may exist at the end of the lease term.

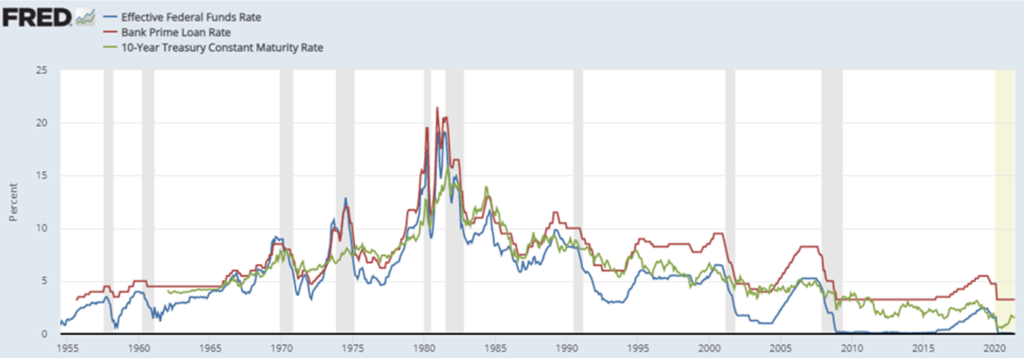

A variety of survey data pertaining to lending rates for permanent and interim financing also exists. RealtyRates.com publishes an investor survey quarterly with rates specific to a variety of commercial real estate industries, including healthcare / senior housing. The 2nd Quarter 2021 version of this survey featured the following for the Health Care / Senior Housing sector:

- Permanent Financing: Rates were quoted on a spread over base basis, with “base” defined as the 10-year Treasury. These ranged from 134 basis points (bps) to 670 bps, with an average of 364 bps. Overall interest rates ranged from 2.60% to 7.96%, with an average of 4.90%. DCRs ranged from 1.10x to 2.25x, with an average of 1.50x, while LTVs ranged from 0.50 to 0.90, with an average of 0.71. Amortization periods ranged from 15 to 40 years, with an average of 25 years, while loan terms ranged from 3 to 25 years, with an average of 14 years.

- Interim Financing (Construction): On a spread over base basis, rates ranged from 95 bps to 685 bps, with an average of 394 bps. Overall interest rates ranged from 4.20% to 10.10%, with an average of 7.19%, with loan fees of 1.50% to 5.50% (average of 3.36%). LTVs ranged from 0.50 to 1.0, with an average of 0.78. Loan terms were 12 to 24 months, with an average of 18 months. Amortization was interest only.

The preceding summary of the various indices reveals the range of terms that exist in the capital markets. In a build-to-suit scenario, the overall market trends, as well as the specifics associated with a particular site or tenant, will affect the appropriate overall development terms. If a JV entity between two healthcare providers (health system and outpatient platform company or physician group, for instance) involves providing debt to the project, then the terms should be consistent with FMV and commercially reasonable given the overall transaction profile.

If a “rent constant” is being fixed in advance, then a prudent tenant and landlord will both evaluate capital market trends (and likely projections) to determine where cap rates (or the debt markets) are likely to be at the time that either the debt is secured, or the project is sold (or both). If the funding is tied to a certain capital markets indicator, then tenant and landlord should evaluate long term trends in the selected index.

Regardless of structure (negotiated rent per square foot vs. predetermined rent factor vs. rent tied to a capital markets index), the appropriate spread (and overall development profit) should be considered in the context of the various risks and responsibilities that landlord/developer versus tenant are undertaking.

This concludes Part 3 of VMG Health’s four-part series.

Footnotes:

[1] In the December 2, 2020 Final Rule, CMS provided updated and detailed guidance on commercial reasonableness (“CR”). CR is a complex topic and a detailed CR discussion is beyond the scope of this article. For questions regarding commercial reasonableness in the context of a new real estate development, please contact VMG Health.

Categories: Uncategorized

Built-to-Suit: Constructing a New Building? Transaction Structuring, FMV, and Compliance Considerations – Part 2: Credit Ratings and BTS Healthcare Assets

June 22, 2021

By: Victor McConnell, MAI, ASA, CRE, Frank Fehribach, MAI, MRICS, and Grace McWatters

*This is Part 2 in VMG’s series on transaction structuring considerations for new developments. The other parts in this series can be found here: Part 1, Part 3, Part 4.

Are you constructing a new building, on or off of a hospital campus? If so, there are unique considerations that investors, JV partners, developers, hospitals, physicians, and other parties to a new development should evaluate. For instance, if a hospital and/or a physician partner are developing a building and then leasing it to a JV entity, the associated lease rate and overall development terms will likely need to be documented as being commercially reasonable [1] and within fair market value (“FMV”) parameters. For investors constructing build-to-suits, primary concerns may revolve around analyzing the risk associated with a particular tenant. For hospitals and physician partners who are joint venturing on a development, the key analyses may involve appropriate allocation of risk, responsibility, and capital vs. non-capital contributions that each party is making to the development. If parties are sharing in development responsibility and risk, then a careful analysis should be undertaken to ensure that parties receive appropriate return given their risk, as well as their various capital and non-capital contributions.

This article will provide an overview of key issues to be considered prior to, during, and subsequent to construction of a new building. For assistance with transaction advisory, cost benchmarking, FMV analysis, commercial reasonableness opinions, or other consulting services, please contact VMG Health.

In Part 1, we covered the economics of build-to-suit projects, the rates and returns associated with their development, as well as the types of costs and fees that can be expected during various stages of these projects. Part 2, which is presented below, will cover variance in credit ratings, lease quality, and tenant risk and how these factors can influence the profitability of a project. Parts 3 and 4 will be presented separately and will cover the relationship between capital markets and BTS rates, as well as rent factors and amortization rates, and how these factors impact development terms.

Credit Ratings and Their Impact on Build-to-Suit Deals

The terms that a landlord/developer will offer a tenant in a build-to-suit scenario are affected by the tenant’s credit rating. Some build-to-suit projects include lease guarantees from parent entities (hospital systems, platform companies, etc), while others are guaranteed by a facility-specific LLC or a physician group. A credit guaranty may be a non-capital contribution to a development that should be taken into account in a JV structure (or in setting the RoC rate with the developer). In the event that a JV develops a new building, but development responsibilities and capital (or non-capital) contributions vary between the parties, then adjustments may be required (in terms of ownership percentages versus cost, or in terms of the go-forward project lease rate) to ensure that the deal structure is consistent with FMV and is commercially reasonable.

Credit ratings and tenant risk are complex topics which have been analyzed extensively within the commercial real estate sector. A “credit tenant” is defined differently by different sources. One definition is as follows: “A tenant in a retail, office, or commercial property with a long history in business, strong financial statements, or a large market presence that could be rated as investment grade by a rating agency. Because of the likelihood of honoring their leases, credit tenants are considered less risky to lease to, and developments with credit tenants as anchors are considered less risky investments for lenders.” [2]

It is worth noting that the preceding definition defines a “credit tenant” as not strictly limited to an entity with a credit rating, though some market participants do define it as such. For instance, a research paper by Sonneman and Yerke published in The Counselors of Real Estate in 2013 defined a credit tenant as “one whose bond issues fall within the investment grade levels set by one of the three major rating agencies.” [3] However, the article also defines an ideal single-tenant, investment grade lease as: being long-term with no early termination, a triple-net or absolute net structure, periodic rent increases, and featuring multiple renewal periods.

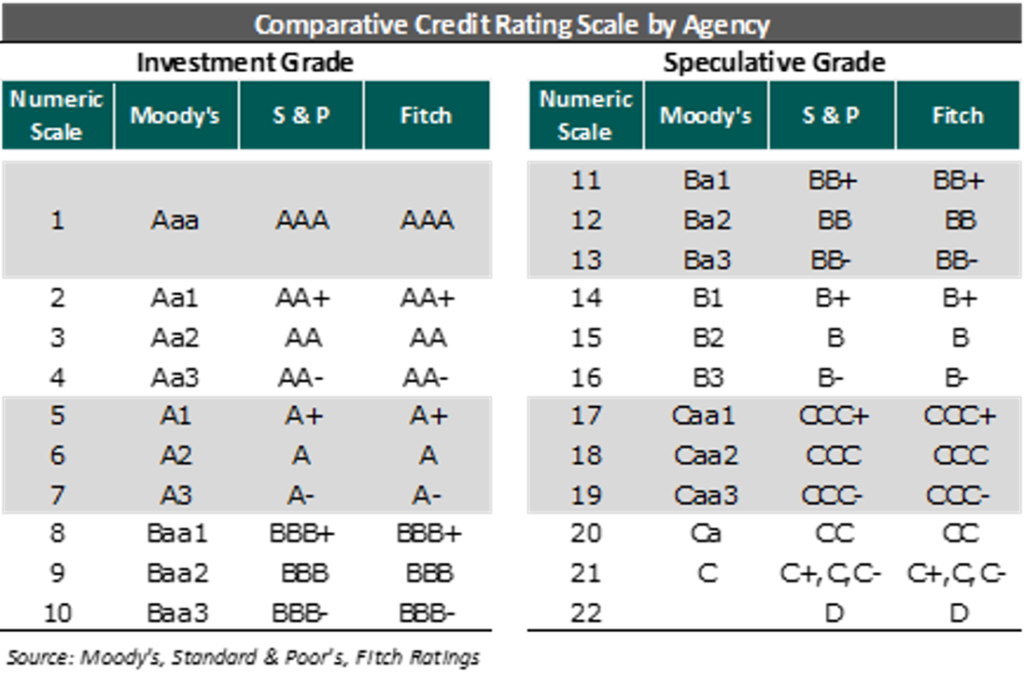

The accompanying chart (“Comparative Credit Rating Scale by Agency”) provides comparison of the credit ratings for the three main credit rating agencies: Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (“S&P”), and Fitch Ratings.

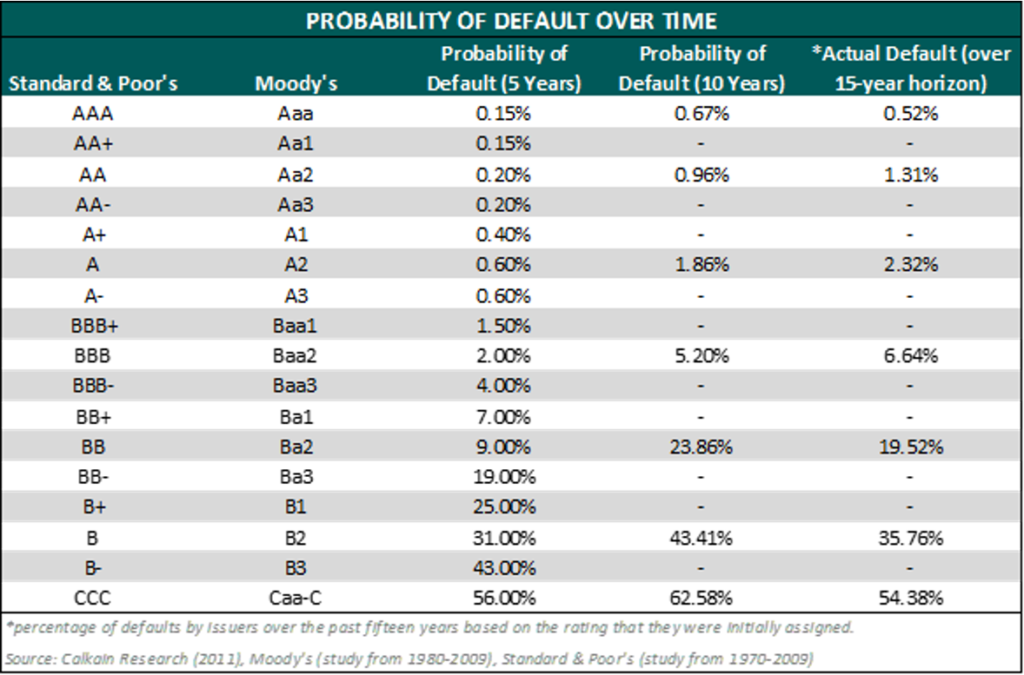

The ratings agencies have periodically evaluated their ratings relative to actual default rates and have assigned default probabilities for each rating, as summarized in the accompanying table (“Probability of Default Over Time”).

Calkain, a boutique commercial real estate firm focused in the net lease market, has a research arm which provides extensive market commentary within the net lease sector and has published numerous surveys and white papers. In a 2011 study of credit ratings and cap rates, Calkain noted that “Moody’s also measured default rates from 1970-2009 based on a company’s issued rating. At 5, 10, and 20 years, investment grade companies’ likelihood of defaulting were .973%, 2.503%, and 6.661% respectively. On the other hand, speculative grade companies over the same time horizons were 21.359%, 34.005%, and 49.649%, respectively.” [4] Entities with inferior credit ratings not only tend to default at a greater overall rate over a long period, but they also default more quickly when starting from a given point in time. For instance, Calkain’s paper also stated that “According to a study done by S&P from 1981-2009, the lower the credit rating, the faster the time of default. For example, the AAA rated companies that defaulted did so on average at 16 years from the issuance of rating, BBB and CCC rated companies did so at 7.5 and 0.9 years respectively. This shows that not only do lower rated companies have a higher probability of default, but [default] also happens at an accelerated pace with lower rating.” Within the context of the single-tenant, net-lease sector, a default likely equates to the early termination of a lease. The consequences of early lease termination depend on the lease rate relative to market as well as the risks and costs related to re-tenanting the property. Real estate investors in the single-tenant net lease sector must evaluate these considerations in their acquisition decisions. For a single-tenant, net-leased specialty asset, the cost of re-tenanting the property can be significant. In a build-to-suit scenario, a developer, lender, or investor must carefully evaluate potential downside risk scenarios in determining an appropriate RoC rate.

A paper titled “Net-Leased Single-Tenant Risks” published by George Renz in the November – December 2014 CCIM Institute publication attempted to address the question of the likelihood of a tenant actually paying rent over a 10-20+ year time horizon. [5] The paper stated that “an analysis of 100 NLST [net-lease single-tenant] deals answers the question. Out of 100 transactions with locations nationwide ranging in value from $322,000 to $9 million, only six tenants filed bankruptcy or did not pay rent. The breakdown: 1) of 70 investment-grade and national tenants, no investment grade tenants defaulted and only one national tenant defaulted; 2) of 30 franchisee, regional, and local tenants, five defaulted.” The paper provided minimal detail regarding the 100-transaction sample, and thus extrapolating any broad default probabilities would be difficult. That said, the article serves as another example of the general commercial real estate investment community’s continued attempt to evaluate risk within the single-tenant net lease sector; the activities of these market participants ultimately affect investment decisions (and, correspondingly, cap rate trends).

Other researchers have analyzed real estate lease backed securities in evaluating risk. McMurray and Mundel noted in a 1997 academic study that “for risky lessees, i.e. all lessees where there is a possibility of default in some period t < T, a credit spread must be added to the risk-free discount rate, r, in the equations shown previously.” [6] The paper noted significant risk factors impacting normative lease credit spreads including lease maturity, mean reversion, correlation, and volatility.

The purpose of discussing real estate backed securities relative to an examination of the build-to-suit healthcare real estate market is to illustrate the expansion of the buyer pool which occurs when a property features a lease backed by a credit-worthy corporate entity; properties which lack credit rated tenants could not be included within an investment grade real estate lease backed security, thus eliminating a portion of the buyer pool (institutional buyers that only invested in highly rated securities; significantly, this portion of the buyer pool typically has a lower cost of capital). If the combination of real estate, lease quality, and tenant quality is sufficient to attract institutional buyers, an impact on the property’s value (i.e. cap rate) would be expected.

In some cases with a specialty built healthcare asset (particularly on a hospital campus), the ability of a developer/landlord to sell may be subject to certain restrictions. However, even absent a sale, the risk profile associated with the lease income stream affects the debt terms achievable in the capital markets; while debt issuance is different than the sale of a property, the terms of the debt ultimately affect the developer/landlord’s profitability.

The previously referenced 2011 Calkain study noted “each lender has different criteria for who they lend to. For example, CTL [Credit Tenant Lease financing] lenders will only lend to investment tenants regardless of real estate. On the other hand, insurance companies such as American Fidelity assess all types of companies and measure them through H and Z scores to determine if they qualify. […] On [American Fidelity’s] list of approved retail credits, there were 71 retailers they would lend to and 55 not approved.” This excerpt illustrates another issue which can cause cap rate compression: superior available financing terms for properties with comparatively lower risk profiles. If a buyer can access financing at a lower rate, then it follows that the buyer would be willing to acquire the property at a lower cap rate, as the spread between the cap rate and the financing represents an arbitrage opportunity.

VMG has previously performed extensive research into the impact of credit guarantees on a variety of outpatient and inpatient healthcare assets. The impact of a credit tenant is more significant, generally, when the underlying real estate is less valuable. When the underlying real estate features strong fundamentals (i.e. growing demographic trends, high land values, strong occupancy rates, increasing rent rates, and so forth), then the impact of a credit guarantee may be diminished.

For further information concerning quantifying the value of a lease guaranty, please contact VMG Health.

The next section (Part 3) in this Build-to-Suit series involves further discussion of build-to-suits and capital markets.

Footnotes & Sources:

[1] In the December 2, 2020 Final Rule, CMS provided updated and detailed guidance on commercial reasonableness (“CR”). CR is a complex topic and a detailed CR discussion is beyond the scope of this article. For questions regarding commercial reasonableness in the context of a new real estate development, please contact VMG Health.

[2] The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 6th Edition (Chicago: Appraisal Institute, 2015).

[3] Sonneman, Donald, et al. “Comparing Value: U.S. Government Office Leases vs. Credit Tenant Leases.” The Counselors of Real Estate, Spring 2013, Vol. 38, Number 1, pp. 20-30.

[4] Caswell, Chris. “Credit Rating Effect on the Marketplace” Calkain Research, reviewed by David Sobelman, Stanley Wyricz, Richard Murphy, Michael O’Mara, Orzechowski, Winston. 2015, pp. 1-15.

[5] Renz, George L. “Net-Leased Single-Tenant Risks.” CCIM Institute, November│December 2014, pp. 22-25.

[6] McMurray, John P., Samuel M. Mundel. “Real Estate Lease-Backed Securities.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, September 1997, pp. 1-84.

Categories: Uncategorized

Built-to-Suit: Constructing a New Building? Transaction Structuring, FMV, and Compliance Considerations

June 22, 2021

By: Victor McConnell, MAI, ASA, CRE, Frank Fehribach, MAI, MRICS, and Grace McWatters

*This is Part 1 in VMG Health’s series on transaction structuring considerations for new developments. The other parts in this series can be found here: Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.

Are you constructing a new building, on or off of a hospital campus? If so, there are unique considerations that investors, joint venture (“JV”) partners, developers, hospitals, physicians, and other parties to a new development should evaluate. For instance, if a hospital and/or a physician partner are developing a building and then leasing it to a JV entity, the associated lease rate and overall development terms will likely need to be documented as being commercially reasonable[1] and within fair market value (“FMV”) parameters. For investors constructing build-to-suits, primary concerns may revolve around analyzing the risk associated with a particular tenant. For hospitals and physician partners who are joint venturing on a development, the key analyses may involve appropriate allocation of risk, responsibility, and capital vs. non-capital contributions that each party is making to the development. If parties are sharing in development responsibility and risk, then a careful analysis should be undertaken to ensure that parties receive appropriate return given their risk, as well as their various capital and non-capital contributions.

This article, which is presented as a four-part series, will provide an overview of key issues to be considered prior to, during, and subsequent to construction of a new building. For assistance with transaction advisory, cost benchmarking, FMV analysis, commercial reasonableness opinions, or other consulting services, please contact VMG Health.

PART 1: Overview, BTS Economics, and Development Risk & Responsibility

Build-to-Suit – What is It?

The term “build-to-suit” (“BTS” or “built-to-suit”) is not formally defined within The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal; however, the Commercial Real Estate Encyclopedia defines it as “a type of real estate transaction where a property owner or developer will construct a building for sale or lease that will be built to the tenant’s or buyer’s specifications.” Within healthcare settings, developers commonly develop buildings for tenants who will then lease the building subsequent to construction. In some cases, a hospital (or JV between a hospital and a physician group) may develop a new building and then master lease it to an operating entity. In other cases, the building may be constructed by a third party (developer, REIT, private equity, etc.) who will then lease the space to a healthcare tenant.

Economics of a Build-to-Suit

In a typical build-to-suit arrangement that is to be 100% leased by a single tenant, a developer will construct a property that the tenant will lease at a percentage multiplied by the developer’s “all-in” [2] cost. Market participants differ in the terminology utilized to refer to this “build-to-suit rate”; common terms include return-on-cost (“RoC”) rate, initial yield rate, rent constant (or factor), development constant, or developer’s yield.

In these arrangements, a developer receives a return via the rent collected over the course of the lease term, as well as via reversion upon project sale (unless there is no residual, in which case a developer achieves their targeted return via rent collected during the holding period). The developer will generally anticipate selling the property at an overall capitalization rate (“cap rate”[3]) that is below the build-to-suit rate. Factors which can affect the RoC rate are similar to factors which affect cap rates. These factors include, but are not limited to: a) tenant creditworthiness; b) financing terms associated with the transaction; c) length of lease term; d) lease escalations; e) a property’s location and physical characteristics, such as design and construction quality; f) expense structure between tenant and landlord; g) renewal probability; h) anticipated reversion; i) trends in the capital markets; j) industry specific trends; k) landlord and tenant motivations; and l) a property’s construction cost and implied lease rate relative to market.

Some developers build and hold projects over a long period, while other seek to sell projects based on a shorter forecasted hold period [4]. Furthermore, the developer is likely borrowing money both during the construction period (an interim construction loan) as well as subsequent to construction (permanent financing). In these cases, the developer will likely anticipate borrowing at a rate that is a certain number of basis points below their build-to-suit rate. Similarly, if a landlord is providing funding for tenant improvements in an existing building, the landlord will typically provide those funds to the tenant at a rate above the landlord’s cost of borrowing. When offering tenant-specific tenant improvement (“TIs”) allowances, a real estate investor will evaluate how much residual value, if any, will remain at the end of the lease term. If the TIs are highly specialized and tenant specific, an investor may seek to amortize the full cost of the TIs into the lease term, as the likelihood of residual value to another tenant is low. In some cases, a landlord may offer an amortization schedule which exceeds the lease term, although the tenant may be required to pay the unamortized cost of the TIs if they choose not to renew the lease.

In structuring a lease associated with a build-to-suit, the overall economics must be carefully considered in order to ensure that each party is receiving a return commensurate with their risk and responsibility.

Evaluating Build-to-Suit Rates

Build-to-suit rates (i.e. rent constants) are highly correlated with cap rates and other capital market indicators. However, specifics concerning lease structure (such as absolute net vs. triple-net) can also affect an appropriate rent constant. For instance, in an absolute net lease structure, a tenant will bear more ongoing capital expenditures during the lease term, which decreases the risk profile for the landlord. Term length also affects an appropriate build-to-suit rate, as longer terms are generally more favorable to landlords due to lowering risk profiles (which can translate to lower cap rates or superior financing options).

VMG has conducted extensive research into cap rate trends across various healthcare real estate asset classes. In the course of our valuation and consulting work pertaining to proposed projects, VMG Health has also interviewed multiple investors, developers, and brokers active in the healthcare real estate market regarding cap rate and build-to-suit data for various assets. While return-on-cost rates offered by build-to-suit developers generally compress along with overall capital markets trends, historical averages for a particular sector, as well as forecasted risks for a particular tenant (and their associated industry) will affect the build-to-suit terms available at any given time.

Cap rates and RoC rates are different, though correlated. As previously noted, when developers build specialty healthcare assets for tenants on a build-to-suit basis, the developer’s profit is often a function of the “spread” between their RoC rate and their exit cap rate. For instance, as noted previously, if a developer constructs a project at a 9.0% RoC rate and then immediately sells the project for an 8.0% cap rate upon completion (a 100 BPS spread), the developer will have made a 12.5% unlevered profit (without considering timing and other certain factors). A project built at a 7% RoC and sold at a 6% cap rate would represent a 16.7% unlevered profit for the developer.

In addition to the project-specific or tenant-specific risk factors which can affect risk and profit expectations, the size of the development can also affect the spread sought by the developer, as developer profits tend to be smaller on a percentage basis for a $50 million project as compared to a $5 million project.

Ultimately, build-to-suit rates and development profit are largely affected by the risk associated with the tenant, as well as with the risks and responsibility allocation between developer and tenant.

Tenant risk will be discussed later in this article, whereas an overview of development risk and responsibility is presented in the following section.

Development Risk and Responsibility

In constructing a new real estate development (or performing significant renovations on an existing building), a number of different direct costs [5] and indirect costs [6] are required. Furthermore, time and expertise are required to manage various parts of the construction process. Developers also commonly take a variety of risks during the development process, and the overall return achieved by a developer is generally considered to represent compensation for the risk taken on by the developer. There are a wide array of potential risks (and time expenditures) that a developer may incur, including items such as, but not limited to, the following: a) market analysis and feasibility studies to assess demand prior to development; b) site selection and land acquisition, including potential negotiations with multiple sellers to assemble a large development tract; c) environmental assessments; d) site plans, permitting, and building plans; e) zoning analysis and applying for zoning changes or use exceptions; f) infrastructure assessment and improvement; g) construction financing; and h) other factors. A developer must also consider and factor in the potential for project failure at various points in the early stages, which could result in significant financial losses for the developer. The early-stage land development process can be delayed by a variety of factors, including environmental issues, design delays, zoning and entitlement delays, appeals (and/or litigation) from nearby property owners or other interest parties, and disputes between a developer and the local municipality or other regulatory authorities. During the construction process, a developer may also face risks associated with construction delays, cost overruns, financing issues, pre-leasing risk, and other factors. Subsequent to completion, a developer may continue to have various risks in a project, depending on lease-up, potential exit strategy, tenant default, property management, ongoing capital expenditures, and other considerations.

Given the extended timeline in which development risk is incurred, the timing of an equity investment in an LLC which owns a new building affects the way in which the ownership interest is valued. Assuming an investment is made at very beginning, when the proposed project is just a plan, then the pricing for an equity buy-in into the real estate ownership entity may correspond more closely to direct cost and indirect cost of the development. This is because all investors paying for the construction of the project are sharing in the risks of the project’s development. This assumes that project risks are shared evenly and equitably among JV partners; in these cases, a project’s entrepreneurial profit/incentive would generally align accordingly.

When a project is complete, the sale of a minority equity position (or the sale of a 100% ownership position) in the project will generally no longer correspond as closely to the aggregate construction costs, as the development risk has already been incurred. Thus, post-completion, equity positions should generally be based upon their fair market value (because the equity investor post-completion is no longer taking on development risk and thus would not reasonably be expected to participate in the entrepreneurial profit/incentive associated with the development).

A real estate development can involve a developer and a variety of individuals or companies responsible for managing or overseeing components of a project. Within commercial real estate development, developers are sometimes hired on a fee for development basis, with developer’s fees often included within a project’s budgeted soft costs; this generally represents a lower risk profile for a developer. Developer’s fee is defined as follows: “typically, a payment by a property owner to a third party for overseeing the development of a project from inception to completion, included among the direct and indirect costs of development. Sometimes, the term is used to describe the time, energy, and experience a developer invests in a project as well as a reward for the risk undertaken.” [7] Developer’s fee is distinct from “developer’s profit”, which is defined as “The profit earned by the developer of a real estate project.” Developer’s profit is also sometimes referred to (by appraisers and real estate analysts) as entrepreneurial profit, and the two terms can represent the same concept, though certain market participants may apply the terms differently.

Entrepreneurial profit is defined as: “A market-derived figure that represents the amount an entrepreneur receives for his or her contribution to a project and risk; the difference between the total cost of a property (cost of development) and its market value (property value after completion), which represents the entrepreneur’s compensation for the risk and expertise associated with development.” Entrepreneurial incentive is defined as: “The amount an entrepreneur expects to receive for his or her contribution to a project. Entrepreneurial incentive may be distinguished from entrepreneurial profit (often called developer’s profit) in that it is the expectation of future profit as opposed to the profit actually earned on a development or improvement.”

It should be noted that, over a large enough sample, entrepreneurial profit and entrepreneurial incentive should be roughly equivalent. However, as illustrated by the definitions, entrepreneurial profit is a historical fact (based on the actual profit achieved), whereas entrepreneurial incentive is based on profit that is anticipated.

Entrepreneurial profit (or developer’s profit) and developer’s fees are separate and distinct from certain other soft costs, such as “contractor’s overhead” and “contractor’s profit.” Contractor’s overhead is defined as “The general and administrative costs, over and above the direct costs of material and labor, that are estimated by a contractor on any construction work.” Contractor’s profit is defined as “The amount by which the fee received by a contractor for work performed exceeds the total direct costs of material, labor, and overhead. [8]

Developer’s profit can include construction management and project management, as well, though construction management and project management are not defined terms within The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal. [9] However, both are required to construct a building and are roles that are often filled by the developer or the general contractor. Pricing for these services can vary and depend, in part, on whether the party providing the service is profiting in other ways from the development (e.g. a developer who is also the owner or landlord). If a developer is overseeing a project but is not contributing equity, then a developer will typically charge a fee for their time and expertise. If a developer is contributing equity or going at risk for other project components, they may price certain fees differently as they will likely evaluate their overall return on a project relative to the risk (and required time, expertise, and capital outlay). Furthermore, as noted, some developers may provide services on a fixed fee basis, while others will provide services as a percentage of costs or as part of their overall project role (e.g. a developer with significant risk and equity in a project may expect to provide a variety of services over the development and construction lifecycle). Thus, in some instances, developer’s pricing and compensation may also implicitly or explicitly reflect brokerage fees [10], site selection [11] services, or other items.

The detailed discussion of various risks and responsibilities involved in the development process is presented in order to illustrate the complexity of allocating risk and responsibilities between parties in a build-to-suit transaction (and ensuring that the transaction structure appropriately accounts for these factors).

If you are evaluating a potential build-to-suit project and require third-party expertise to assist with ensuring that the transaction structure is fair and reasonable to each party participating in the development, please contact VMG Health for assistance.

The next portion (Part 2) of this series will focus on credit ratings and their impact on build-to-suit projects.

Footnotes:

[1] In the December 2, 2020 Final Rule, CMS provided updated and detailed guidance on commercial reasonableness (“CR”). CR is a complex topic, and a detailed CR discussion is beyond the scope of this article. For questions regarding commercial reasonableness in the context of a new real estate development, please contact VMG Health.

[2] “All-in” costs may be defined differently by different developers for different projects in different markets. Developers take different approaches to pricing projects in a competitive bid situation, with some shifting more profit to a projected residual, while others may seek a higher developer fee or higher rent rate. Generally, however, “all-in” costs encompass all of a developer’s hard and soft costs, including land acquisition, building design and construction, site work, project financing, and so forth.

[3] A “capitalization rate” is defined by The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal as “a ratio of one year’s net operating income provided by an asset to the value of the asset; used to convert income into value in the application of the income capitalization approach.” Within the single-tenant, net-leased sector, there are slight variances in the methodologies by which investors calculate a capitalization rate. A detailed discussion pertaining to these variances is beyond the scope of this article.

[4] A hold period, or “holding period”, is defined as “the term of ownership of an investment”. Source: The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 6th Edition (Chicago: Appraisal Institute, 2015).

[5] Direct costs are defined by The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal as “Expenditures for the labor and materials used in the construction of improvements; also called hard costs.”

[6] Indirect costs are defined in The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal as “Expenditures or allowances for items other than labor and materials that are necessary for construction, but are not typically part of the construction contract. Indirect costs may include administrative costs, professional fees, financing costs and the interest paid on construction loans, taxes, the builder’s or developer’s all-risk insurance during construction, and marketing, sales, and lease-up costs incurred to achieve occupancy or sale. Also called soft costs.”

[7] The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 6th Edition (Chicago: Appraisal Institute, 2015).

[8] Ibid.

[9] An example of a definition of “construction management fee” sourced from lawinsider.com is noted as the “fee or other remuneration for acting as general contractor and/or construction manager to construct improvements, supervise and coordinate projects or to provide major repairs or rehabilitation on a property.”

[10] When acquiring vacant land for development or buying, selling, or leasing a building, fees are often paid to a third-party broker based upon a percentage of sales or lease price. Brokerage fees (i.e. broker’s “commission”) are defined by The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal as follows: “an agent’s compensation for performing his or her duties; in real estate, a percentage of the selling price of property or a percentage of rentals that is received by the agent.”

[11] Some developers perform site selection services in conjunction with other development services. Brokers will also assist in site selection as part of their brokerage services in assisting a client in buying a property. Furthermore, consultants who specialize in site selection and appraisers with expertise in site selection are sometimes separately engaged in evaluating a potential new location, though their services can sometimes include a more comprehensive feasibility analysis. In some cases, the company providing site selection services will also be involved in conducting feasibility studies and/or limited negotiation with the seller of the land.

Categories: Uncategorized

Post-COVID Hospital Guidance: Comparing Full-Year Guidance from Public Hospital Operators before the COVID-19 Pandemic and One-Year Later

June 9, 2021

Last March, the United States declared a national emergency related to the coronavirus (“COVID-19”) pandemic. At the time and throughout the beginning of the pandemic, meaningful economic factors were unknown including the evolution of the disease, the extent of its economic impact, and the results of steps taken and yet to be taken by the federal government, financial institutions, and market participants. As a result, many healthcare operators suspended the disclosure of earnings guidance. Now, after a year of experience with the COVID-19 pandemic, operators have resumed sharing their expectations of future financial performance. VMG Health analyzed select guidance figures from the four main public hospital operators to better understand the industry’s perspective on operations in a post-COVID world.

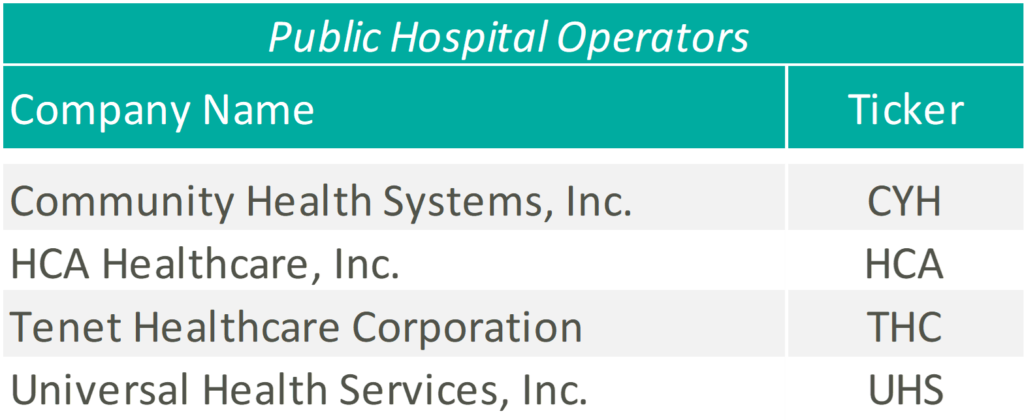

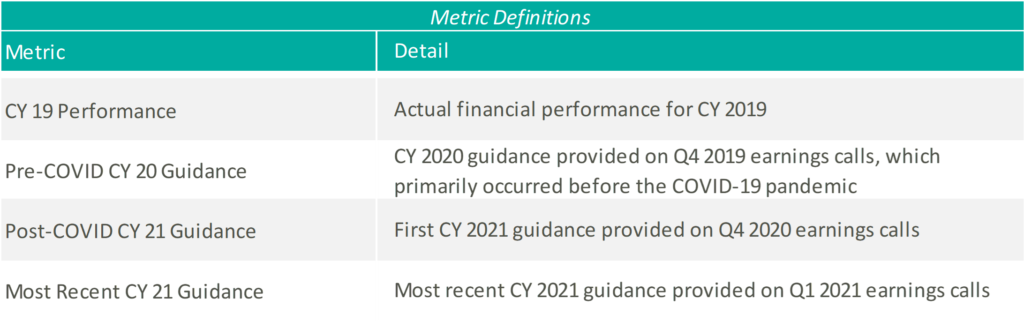

Please see below for a list of the public hospital operators examined, as well as further detail regarding the various metrics considered.

Revenue

Except for CYH, initially and most recently, the hospital operators expect CY 2021 revenue levels at or above those estimated at the beginning of CY 2020, and well above their CY 2019 performance. Please note, CYH completed a planned divestiture program towards the end of 2020, making it difficult to compare CY 2019 performance to the forward guidance figures.

At the end of 2020, when the hospital operators were once again comfortable providing guidance figures, the management teams anticipated continued COVID volumes during the first half of the year, with a return to more normal levels by the second half of the year. HCA noted that they expected 2021 volumes to grow above 2020 levels but trend slightly below 2019 levels, while THC believed their 2021 volumes would improve on 2019.

A few months later, during the Q1 2021 earnings calls, the operators noted strong first quarter results and tailwinds from the extension of sequestration through the end of the year. As a result, HCA tightened their CY 2021 revenue guidance and THC increased their CY 2021 revenue guidance. Although UHS kept their CY 2021 guidance figures flat, they noted that they “remained comfortable” in their ability to achieve the projected revenue levels and viewed sequestration as a “cushion” not currently factored into their guidance figures.

Adjusted EBITDA

Except for UHS, initially and most recently, the hospital operators expect CY 2021 adjusted EBITDA levels near or above those estimated at the beginning of CY 2020 and their CY 2019 performance.

As mentioned previously, the operators pointed towards a strong first quarter performance as rationale for tightening or raising their CY 2021 EBITDA guidance ranges. Additionally, HCA, CHS, and THC discussed the continued focus on cost saving initiatives throughout 2021 to combat expense pressures related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the Q4 2020 and Q1 2021 earnings calls, UHS management cited similar expense pressures, primarily related to labor, associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Generally, the UHS team expects the labor pressures to ease as the volume of COVID patients declines, but at a slower pace.

CONCLUSION

Although uncertainty remains, with a full year of COVID-19 operations under their belts, hospital operators have become more comfortable discussing go-forward performance. As Daniel Cancelmi, CFO and Executive VP at THC said during the Q4 2020 earnings call, “Although there are various uncertainties as to how the pandemic will impact us this year, we believe we have sufficient visibility and confidence as to how our business will perform during the ebbs and flows of the pandemic to enable us to provide investors an outlook of our projected results this year.” Additionally, Kevin Hammons, Executive VP and CFO at CYH, noted that although uncertainty remains, there are multiple ways to achieve the guidance figures. After a hard year for the healthcare industry, it is encouraging to see the hospital operators look forward again and provide a generally positive outlook related to the recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Categories: Uncategorized

Are You Under (or Over) Insured? Analyzing Replacement Cost for Hospital Systems, Investors & other Healthcare Providers

June 4, 2021

Evaluating the replacement cost of the facilities and equipment for your hospital system should involve a formalized, detailed process, whether occurring at regular intervals or on an as-needed basis due to specific events (property damage due to natural or man-made causes, acquisitions, new construction or renovation).

There are risks to being over insured or under insured. The primary risk of being over insured relates to increased operating costs which occur through higher premiums, higher deductibles, or both. If property insurance is being passed through to tenants in a triple-net lease structure, it could also create leasing challenges due to higher operating expenses. Or, if the leases are on a “gross” basis, the higher operating expenses can diminish the building’s profitability.

Being under insured can create significant financial exposure. For instance, a casualty event could result in large, unexpected out-of-pocket costs which could limit the ability of a hospital system to pursue other strategic initiatives. For a hospital system operating on thinner margins, this occurrence could be financially catastrophic.

The specialty nature of most healthcare properties and the associated construction costs require specific expertise and data. Some insurers, consultants, or valuation professionals may not be aware of the incremental buildout costs associated with higher cost building components such as imaging, operating rooms, radiation treatment vaults, and so forth. Furthermore, some property types and specialty features have seen cost increases which are higher than the overall average for general commercial buildings or office buildings. The replacement cost for surgical centers, cancer centers, imaging centers, acute-care hospitals, critical-access hospitals, and commercial laboratories must be tested against the proper market cost data by professionals with the appropriate specialized experience to ensure that risks are properly mitigated. A similar approach involving current market cost benchmarking should be used to evaluate the replacement cost of tangible personal property and other expensive and sophisticated equipment within these facilities (robotic surgical/navigational systems, MRI, CT Scan, radiation therapy systems, and laboratory testing/analyzer equipment).

The beginning of any meaningful replacement cost analysis should start in determining the appropriate replacement cost definition and parameters which are most applicable to a hospital’s insurance policy. There are several definitions available for replacement cost and total insurable value (TIV) within the marketplace, and the specific insurance policy definition may have variances that should be considered. Definitions of total insurable value may or may not include all components of owned property, and a particular policy may protect an amount less than the replacement cost or total insurable value for the purpose of lower premiums or deductibles. A few pertinent definitions from industry sources include the following:

- The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 6th Edition defines replacement cost as “The estimated cost to construct, at current prices as of a specific date, a substitute for a building or other improvements, using modern materials and current standards, design, and layout.”

- The American Society of Appraisers define replacement cost new as “The current cost of a similar new property having the nearest equivalent utility to the property being appraised, as of a specific date.”

- The International Risk Management Institute, Inc. defines total insurable value (TIV) as “A property insurance term referring to the sum of the full value of the insured’s covered property, business income values, and any other covered property interests.”

- Marshall Valuation Service (MVS) MVS defines replacement cost as “The total cost of construction required to replace the subject building with a substitute of like or equal utility using current standards of materials and design. These costs include labor, materials, supervision, contractors’ profit and overhead, architects’ plans and specifications, sales taxes and insurance.”

After evaluating the nuances within the definition applicable to a particular hospital’s policy, a professional can account for potential non-perishable items or other components not covered. This could include building foundations, site improvements, certain categories of profit, or other equipment-specific soft costs such as installation, calibration, and testing. The investigative process itself could expose omissions in the policy that need to be re-evaluated. Another consideration when evaluating the appropriate premise of value is that fair market value is likely not a reliable proxy for insurable replacement cost. Fair market value includes depreciation and obsolescence related to loss in value due to physical wear and tear, functional inefficiencies, and/or economic and other external factors. Similarly, book value, either gross book value or net book value disclosed in a hospital’s financial statements, should not be utilized for insurance purposes. Book value is generally based on capitalized cost, as of a specific acquisition date, and does not reflect changes in cost since installation.

In addition to our experience evaluating replacement cost for healthcare buildings, VMG Health has extensive experience providing medical equipment replacement cost analysis and physical inventory services for hospital systems and other healthcare entities. Some of VMG’s recent experience in this sector is summarized below.

- Equipment: Recent and relevant work related to medical equipment replacement cost analysis includes the following:

- 25 acquisitions for a 13-hospital southeastern non-profit health system.

- Fixed asset management for a 2-campus hospital in Florida.

- Physical inventory/equipment valuation for a 2 million square-foot medical and research center in the Middle East.

- Real Estate: Recent experience with real estate replacement cost analysis includes:

- RCN For Health System Insurance Policy Analysis – Recently completed comprehensive replacement cost analysis for a non-profit health system related to owned properties. This involved property-by-property analysis of ~5 million square feet of real estate assets across a wide array of property types. VMG conducted a site visit sampling and provided a comparison of values versus previous insurable values. VMG also constructed an automated model that the health system could leverage on future updates (or changes to) its replacement cost analysis.

- RCN to Assist With Investment Risk Analysis – VMG assisted an institutional real estate investor with analyzing replacement cost in more than a half-dozen different metropolitan areas as part of its underwriting process. The purpose of VMG’s analysis was to assist the investor in analyzing rental rates for new construction within each market relative to the in-place rental rates within an existing portfolio of medical office buildings and other outpatient assets.

- RCN for Surgery Center Platform Company – VMG assisted a surgery center platform company with analyzing replacement cost in various markets to assess the likelihood of competing surgery centers opening up in the given market.

If you are evaluating whether you are under- or over-insured, or otherwise require a replacement cost analysis pertaining to real or personal property, please contact VMG Health. As the market leader in healthcare valuation and advisory, VMG is well-equipped to provide reliable guidance to health systems evaluating this issue.

Categories: Uncategorized

Ambulatory Surgery Centers are in the Spotlight in the OIG Advisory Opinion No. 21-02

May 3, 2021

Written by Bartt B. Warner, CVA

Noteworthy for investors of ambulatory surgery centers (“ASCs”), the Office of Inspector General (“OIG”) released a favorable (low risk) Advisory Opinion (No. 21-02)1 on April 29th, 2021. The Advisory Opinion reviewed a proposed arrangement (“Arrangement”) in which a health system (“Health System”), manager (“Manager”) and five orthopedic surgeons and three neurosurgeons employed by the Health System (“Physician Investors”) would like to invest in a new ASC (“New ASC”). The offer or payment of investment returns from an ASC to an investor constitutes remuneration under the Federal anti-kickback statute. As a result, the Advisory Opinion analyzed if the Arrangement, if assumed, would constitute justification for the imposition of sanctions under the Federal anti-kickback statute.

According to the Advisory Opinion, “the Proposed Arrangement, if undertaken, would generate prohibited remuneration under the Federal anti-kickback statute if the requisite intent were present, the OIG would not impose administrative sanctions on Requestors in connection with the proposed Arrangement under sections 1128A(a)(7) or 1128(b)(7) of the Act, as those sections relate to the commission of acts described in the Federal anti-kickback statute.”

Background

- Health System would own 46 percent of the New ASC.

- Physician Investors would own 46 percent collectively, ranging from 4 percent to 8 percent per Physician Investor.

- The Manager would own 8 percent and develop and manage ASCs throughout the country while providing various management services, consulting, and administrative services to the New ASC.

- Physicians would not have any ownership interest in the Manager.

- The New ASC would allow new investors to invest directly (i.e., no investor would invest through a pass-through entity). In addition, ownership interest in the New ASC would not be contingent on prior or expected volume or value of referrals made by the potential new investor(s).

- Distributions and capital contributions would be made proportionately to an investor’s ownership interest the New ASC.

- The New ASC would be in a newly constructed medical facility owned by a real estate joint venture (“Real Estate Company”) comprised of the Health System, the Physician Investors, and the Manager.

- The New ASC would enter into various space, equipment leases and services arrangements with the Health System and the Real Estate Company.

Referral Risk

Under the Proposed Arrangement, both the Health System and its affiliated physicians, including Physician Investors, would be in a position to generate or influence referrals to various beneficiaries of Federal health care programs to the New ASC. In order to limit the ability of the aforementioned physicians to make or influence referrals, the Health System would disallow any action that required and/or encouraged any physician or medical staff members refer patients to the New ASC or to the Physician Investors. In addition, the Health System would refrain from tracking any referrals made to the new ASC by its affiliated physicians. Further, the compensation received by the affiliated physicians from the Health System would be consistent with Fair Market Value and would not be related in any way, to the volume or value of referrals that the Health System’s affiliated physicians make to the New ASC or its Physician Investors. Lastly, the Manager also attested that it would not make or influence referrals in any way to the Physician Investors or to the New ASC.

Physician Investor Procedures, Income and Program Parameters

According to the Advisory Opinion, the Health System certified the following:

- Each year, a minimum of one-third of the procedures payable by Medicare and performed by a physician in an ASC (“ASC Qualified Procedure”) would be performed at the New ASC.

- For the previous fiscal year or previous 12-month period, every orthopedic surgeon Physician Investor would receive at least one-third of his or her medical practice income from ASC-Qualified Procedures.

- For the previous fiscal year or previous 12-month period, not every neurosurgeon Physician Investor would derive one-third of their medical practice income from ASC-Qualified Procedures.

- Manager would oversee monitoring each Physician Investor’s compliance with the various procedure and medical practice income requirements.

- The majority of the medical practice income for the neurosurgeon Physician Investors is derived from inpatient hospital procedures and would continue even after the investment in the New ASC. However, the neurosurgeon Physician Investors would regularly utilize the New ASC (e.g., to personally perform neuroplasty procedures).

- For ASC-Qualified Procedures, the Physician Investors rarely would refer patients to each other.

- The estimated number of ASC-Qualified Procedures performed in the New ASC and referred by Physician Investors would be less than 1 percent of the aggregate number of ASC-Qualified Procedures performed at the New ASC annually.

- Any space or equipment leased by the new ASC from the Health System and/or the Real Estate Company would comply with the Federal anti-kickback statute safe harbors.

- Any services performed by the Health System and/or Real Estate Company for the benefit of the New ASC would comply with the Federal anti-kickback statute safe harbors.

- Patients referred to the New ASC by any investor will receive written notification of such investor’s ownership in the New ASC.

Safeguards to Mitigate Risk

The Advisory Opinion acknowledged several ways that the Arrangement mitigated risk and keys questions that should be asked in similar situations which are listed below:

- Is the ASC management company directly or indirectly influencing referrals of items or services reimbursable by a Federal health care programs to the ASC?

- Is there physician ownership in the ASC management company?

- Is the health system influencing and/or tracking referrals from its affiliated physicians to the ASC?

- Would the physicians that are investors in the ASC derive at least one-third of his or her medical practice income from all sources for the previous fiscal year or previous 12-month period from the performance of ASC-Qualified Procedures?

- If the answer is no, would the physicians utilize the ASC on a regular basis as part of their medical practice and would the physicians rarely refer ASC-Qualified Procedures to other physician investors in the ASC?

- Does the arrangement contain safeguards to mitigate the risk that the health system would make or influence referrals to the ASC?

- Is the compensation for the health system’s affiliated physicians set at Fair Market Value and not related in any way to the volume or value of referrals?

- Is the offer of ownership in the ASC based on prior or future referrals?

- Are the profit distributions and capital contributions proportionate to an investor’s ownership in the ASC?

- Do the space, equipment rental and services arrangements for the ASC comply with the Federal anti-kickback statute safe harbors?

- Does the ASC and its physician investors provide written notice to patients referred by the ASC investors to the ASC of the referral source’s ownership interest in the ASC?

- Are ASC patients receiving medical benefits/assistance under any Federal health care program treated in a nondiscriminatory manner?

- Does the arrangement include safeguards that prevent ancillary services performed at the ASC to Federal health care program beneficiaries that are not related directly and integrally to primary procedures performed at the New ASC and billed separately to any Federal health care program?

- Is any cost associated with the ASC (unless required by a Federal health care program) not included on any cost report or any claim for payment from a Federal health care program?

Conclusion

Although the Advisory Opinion is favorable, the OIG took the unique stance of relying heavily on the Health Systems’ certifications as previously discussed. In addition to the certifications, the OIG offered a multitude of factors that should be carefully considered for similar arrangements. The safeguards outlined in the opinion demonstrate regulatory guidance remains an important part of investing in health care. All interested parties should consider their referral relationships, as well as guidance provided by this opinion and applicable laws before finalizing a similar arrangement.

Endnotes

1 OIG Advisory Opinion 21-02 available at:

https://oig.hhs.gov/fraud/docs/advisoryopinions/2021/AdvOpn21-02.pdf

Categories: Uncategorized

340B Program & Oncology: What You Need to Know

October 8, 2020

By: Ashley Dyke & Jordan Tussy

The future of the 340B Program remains up in the air as policy makers continue to scrutinize its reimbursement model, citing a potential contribution to rising drug costs and a shift in site-of-service for cancer treatment.8,20 Will the uncertainty of 340B disincentivize hospital consolidation of oncology practices? Is this Program contributing to the shift in oncology treatment from free-standing clinics to hospital outpatient facilities? Many are asking what the future holds for the 340B Program and what the repercussions will be if significant changes are implemented.

340B Program Overview

The 340B Program requires drug manufacturers to offer qualified healthcare providers substantial discounts on select outpatient drugs. The formula used to calculate the “ceiling price”, or the maximum price a manufacturer can charge for a 340B drug, is based on the Medicaid drug rebate formula. It is the average manufacturer price (“AMP”) less a unit rebate amount (“URA”), which is specified in the Social Security Act (“SSA”) and varies by type of drug.21 Generally, the six hospital categories listed below can qualify as a “covered entity” and be eligible for the Program.

- Disproportionate share hospitals (DSHs);

- Children’s hospitals;

- Cancer hospitals (those exempt from Medicare);

- Sole community hospitals;

- Rural referral centers; and,

- Critical access hospitals.

The 340B Program was founded in 1992 with the goal of reducing drug costs for the listed entities and enhance access to prescription medication to vulnerable patients.

In 2010, the 340B Program experienced significant expansion with the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“PPACA”).9 However, in recent years, CMS has enacted several budget cuts targeting the 340B Program and its reimbursement for drug costs, leaving the Program’s future in question. More cuts and/or structural changes to the 340B Program should be expected, as lawmakers re-evaluate the effectiveness of the current payment model.

340B Program Key Milestones

Some of the key dates in the history of the 340B Program are outlined chronologically below.

1992: 340B Program Enacted

- Section 340B of the Public Health Service Act was enacted by Congress. Manufacturers of pharmaceutical drugs were required to enter into a pharmaceutical pricing agreement (“PPA”). The PPA agreement required manufacturers to provide front-end discounts to “covered entities”. Discounts are applied to qualified outpatient drugs to covered entities that serve the most at-risk populations.4