- About Us

- Our Clients

- Services

- Insights

- Healthcare Sectors

- Ambulatory Surgery Centers

- Behavioral Health

- Dialysis

- Hospital-Based Medicine

- Hospitals

- Imaging & Radiology

- Laboratories

- Medical Device & Life Sciences

- Medical Transport

- Oncology

- Pharmacy

- Physician Practices

- Post-Acute Care

- Risk-Bearing Organizations & Health Plans

- Telehealth & Healthcare IT

- Urgent Care & Free Standing EDs

- Careers

- Contact Us

Built-to-Suit: Constructing a New Building? Transaction Structuring, FMV, and Compliance Considerations – Part 3: Build-to-Suits and Capital Markets

June 28, 2021

By: Victor McConnell, MAI, ASA, CRE, Frank Fehribach, MAI, MRICS, and Grace McWatters

*This is Part 3 in VMG’s series on transaction structuring considerations for new developments. The other parts in this series can be found here: Part 1, Part 2, Part 4.

Are you constructing a new building, on or off of a hospital campus? If so, there are unique considerations that investors, JV partners, developers, hospitals, physicians, and other parties to a new development should evaluate. For instance, if a hospital and/or a physician partner are developing a building and then leasing it to a JV entity, the associated lease rate and overall development terms will likely need to be documented as being commercially reasonable [1] and within fair market value (“FMV”) parameters. For investors constructing build-to-suits, primary concerns may revolve around analyzing the risk associated with a particular tenant. For hospitals and physician partners who are joint venturing on a development, the key analyses may involve appropriate allocation of risk, responsibility, and capital vs. non-capital contributions that each party is making to the development. If parties are sharing in development responsibility and risk, then a careful analysis should be undertaken to ensure that parties receive appropriate return given their risk, as well as their various capital and non-capital contributions.

This article will provide an overview of key issues to be considered prior to, during, and subsequent to construction of a new building. For assistance with transaction advisory, cost benchmarking, FMV analysis, commercial reasonableness opinions, or other consulting services, please contact VMG Health.

In Part 1, we covered the economics of build-to-suit projects, the rates and returns associated with their development, as well as the types of costs and fees that can be expected during various stages of these projects. In Part 2, we covered variance in credit ratings, lease quality, and tenant risk, and how these factors can influence the profitability of a project. Part 3, which is presented below, will cover the relationship between capital markets and BTS rates, as well as rent factors and amortization rates, and how these factors impact development terms.

Build-to-Suit Rates and Capital Markets

As previously discussed, build-to-suit rates are significantly affected by cap rate trends, among other factors. Prevailing terms for debt also have a significant impact. For instance, in some CTL structures or loan instruments, a landlord may set a rate based upon a fixed number of basis points above an agreed upon index (such as the U.S. Prime Rate or 10-Year Treasury).

An investor may underwrite a real estate investment assuming a certain “spread” between the rate at which they can borrow money as compared to the rate of return that the property will generate. The cost of debt, the length of the loan, and the loan-to-value (“LTV”) are all significant factors for a real estate investor to evaluate relative to the cap rate at which they will acquire a property or the terms they will offer in a build-to-suit or for a tenant improvement allowance. In some cases, a tenant and landlord may negotiate a predetermined rate for TI amortizations, building additions, purchase options, or put options. In these instances, both landlord and tenant will evaluate the terms relative to alternatives (i.e. alternative investment options and alternative borrowing options).

In the last decade, VMG’s valuation & advisory team has worked extensively within the healthcare real estate sector, including on behalf of lenders, REITs, private equity, as well as health systems and physicians. In a recent consulting project, VMG reviewed information from more than 50 prior projects involving specialty healthcare construction. The goal of this internal data review was to generally evaluate prevailing build-to-suit market trends, as well as to analyze specific agreements where a tenant and landlord agreed on a predetermined price for significant capital expenditures on specialty real estate assets. Furthermore, VMG has analyzed select public REIT filings, historical capital market trends, and pertinent publications and surveys from brokerage firms and academic researchers.

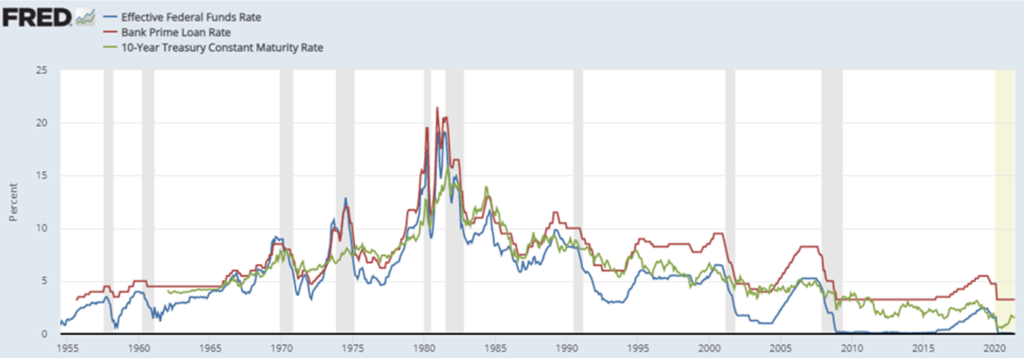

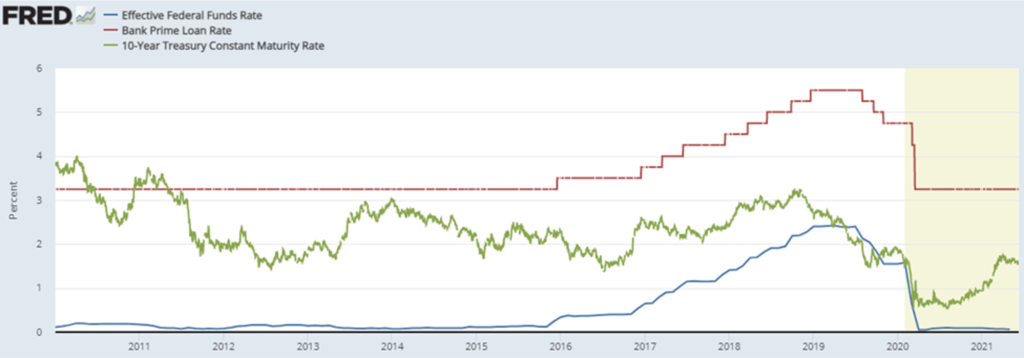

Throughout the commercial real estate sector, prevailing market rates are affected by capital markets conditions, including U.S. Prime Rates (“Prime Rates”). The Prime Rate is generally the lowest rate at which money can be borrowed from commercial banks by non-banks; the Wall Street Journal defines the Prime Rate as “The base rate on corporate loans posted by at least 70% of the 10 largest U.S. banks.” This rate is highly correlated with the Federal Funds Rate. Long-term fixed rates are generally correlated to the 10-Year U.S. Treasury Note (the “10-Year Treasury”). An investor could choose between “locking in” a return on a U.S. Treasury bond (such as the 10-Year Treasury) or investing in the commercial real estate market, where cap rates serve as an indication for an investor’s unlevered return. Unlike a bond with fixed payments, growth in cash flows is anticipated in a real estate investment. Thus, future growth rate assumptions also affect an investor’s overall anticipated return. Examining the spread between the 10-Year Treasury as compared to various commercial real estate (“CRE”) cap rate metrics can reveal changes in investor sentiment, as well as growth expectations. In order to illustrate long-term trends in the capital markets, the following two charts depict the Federal Funds Rate, the 10-Year Treasury Rate, and the U.S. Prime Rate in two periods: since 1950 and since 2010.

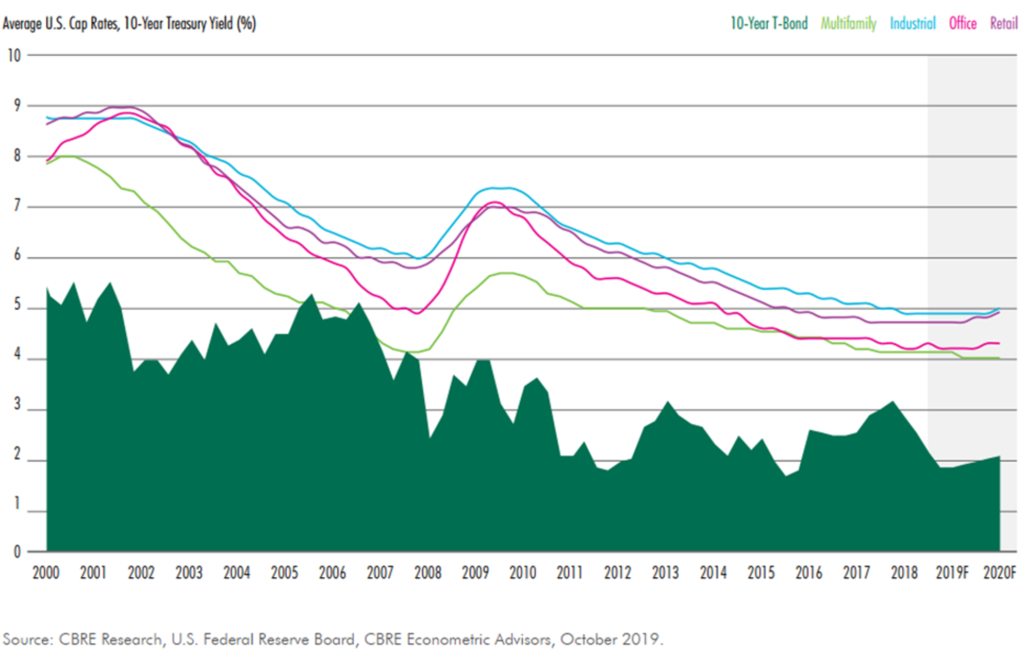

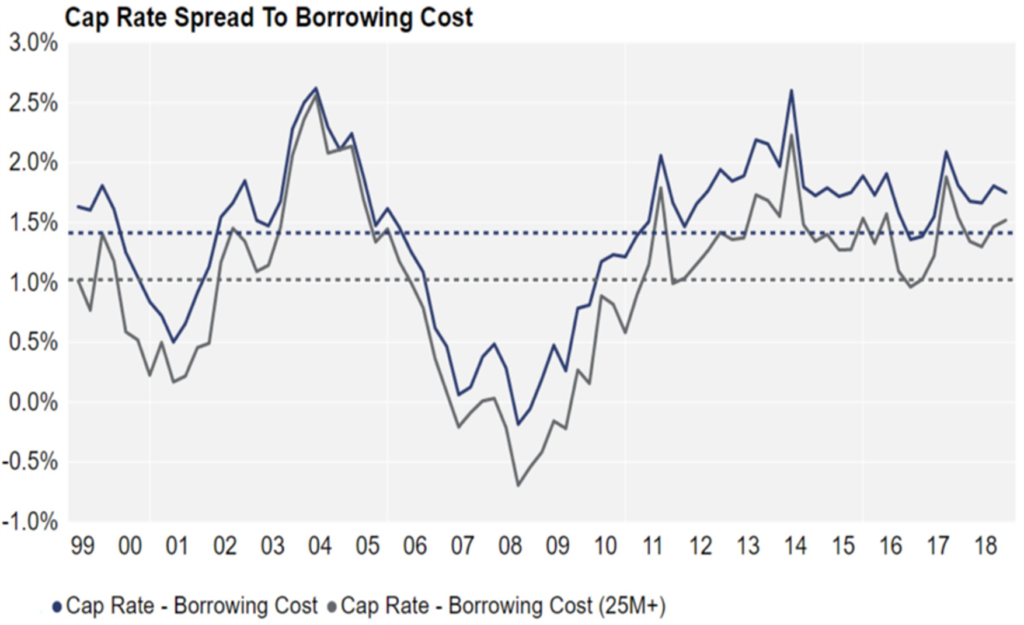

As is evident in the above charts, the three rates are highly correlated, though not perfectly so. These rates also impact the real estate markets, and a variety of research has been performed examining commercial property cap rate trends relative to these rates. The following two charts compare a) core commercial property sectors to the 10-year U.S. Treasury and then b) cap rates as compared to borrowing costs.

Though significant fluctuations are evident, the preceding charts also illustrate general long-term trends related to the spread between the Prime Rate and 10-Year Treasury.

- Between 1990 and 2020, the median spread between the Prime Rate and the 10-Year Treasury was 137 basis points, whereas the 25th and 75th percentile during that period was 42 basis points and 228 basis points.

- Between 1990 and 2020, the median spread between the 10-Year Treasury and the Federal Funds rate was 160 basis points, with a 25th and 75th percentile of 56 and 264 basis points, respectively. Thus, the spread between Prime Rate and Federal Funds rate during this period would be 297 basis points on a median basis.

Prior to the onset of COVID-19 and its impact on the real estate markets, CBRE’s “U.S. Real Estate Market Outlook 2020” noted that “the minimal increase in the 10-Year Treasury yield anticipated for 2020 will help limit cap rate increases and keep the spread about 200 to 300 bps above the risk-free rate next year.” This statement illustrates how institutional real estate investors place real estate returns into context relative to other rate benchmarks, such as the 10-Year Treasury. A study published by Ted. C. Jones, PhD (former chief economist of Texas A&M University’s Real Estate Center) benchmarked commercial real estate cap rates (sourced from Real Capital Analytics) as compared to the 10-Year Treasury on a trailing 12-month (TTM) basis, under the thesis that commercial real estate transactions can take roughly 12 months to close. This study focused on the period from Q1 2001 through Q3 2016. The median spread was 404 basis points, whereas the minimum and maximum were 193 and 509 basis points, respectively. Another study published by Quantum Real Estate Advisors in February 2019 (utilizing slightly different sources and methodology) revealed a general range (between the 10-Year Treasury and CRE cap rates) of 100 to 450 basis points with an average spread of around 300 basis points.

In evaluating a RoC rate for a new development, it should be noted that there is a difference between a rent factor and an amortization rate. By way of illustration, suppose $5,000,000 was provided by a landlord to a tenant for a 10,000-square-foot expansion project ($500/SF). If the landlord and tenant agreed to an 8% rent factor, the rent would be $400,000 per year ($40/SF), e.g. the multiplication of the cost ($5M) by the factor (0.08). However, if landlord and tenant amortized the cost over a 15-year term at 8% (compounded monthly), the annual rent would be $573,391 ($57.34/SF). The same amount amortized over a 25-year term would result in an annual rent of $463,090 ($46.31/SF).

Typically, if a landlord is offering funding based on a rent factor rather than an amortization rate, they are also anticipating residual value at the end of the lease term, or the lease term is long enough that the difference between a rent factor and an amortization rate is minimal. Assuming a 25-year lease term, an amortization rate of 6.75% would result in a similar rent indication as an 8.0% rent constant.

Ultimately, any analysis of a build-to-suit project (or funding of a new addition to an existing hospital campus) should involve careful consideration of and distinction between appropriate amortization rates or rent factors.

Within VMG’s analysis of hundreds of FMV lease rate assessments across the United States, VMG has inquired as to prevailing TI amortization rates for medical office building finish out. The range of TI rates offered by landlords to tenants is affected by capital markets conditions, just as cap rates and other return rates are correlated with various rate benchmarks (such as the 10-Year Treasury). Examples of landlords and tenants agreeing to a formula which predetermines a rate in the future for a lease adjustment or a purchase option are less common, though they do exist. For further discussion of a structure whereby a lease adjustment or purchase option is based on a fixed formula, please contact VMG Health’s real estate division.

Though not always associated with build-to-suits and new construction, the sale/leaseback market also contains pertinent indicators, as well as scenarios which can be somewhat analogous to a build-to-suit. For instance, VMG has reviewed leases executed in sale/leaseback agreements with a REIT whereby the REIT would execute the sale/leaseback at a certain rate and would simultaneously offer to fund certain capital additions at a similar or identical return rate (with this reflected in the lease agreement). Essentially, the REIT was evaluating the risk associated with the tenant/operator as equivalent in two separate scenarios: 1) providing funds in exchange for receipt of the operator’s underlying real estate as collateral (the sale/leaseback) and 2) providing funds for a capital addition to the existing collateral in exchange for the operator’s commitment to lease the capital addition at the same return rate. However, in both cases, in selecting its return rate (whether an amortization rate or rent factor), the REIT is also assessing the likelihood of renewal and the residual value that may exist at the end of the lease term.

A variety of survey data pertaining to lending rates for permanent and interim financing also exists. RealtyRates.com publishes an investor survey quarterly with rates specific to a variety of commercial real estate industries, including healthcare / senior housing. The 2nd Quarter 2021 version of this survey featured the following for the Health Care / Senior Housing sector:

- Permanent Financing: Rates were quoted on a spread over base basis, with “base” defined as the 10-year Treasury. These ranged from 134 basis points (bps) to 670 bps, with an average of 364 bps. Overall interest rates ranged from 2.60% to 7.96%, with an average of 4.90%. DCRs ranged from 1.10x to 2.25x, with an average of 1.50x, while LTVs ranged from 0.50 to 0.90, with an average of 0.71. Amortization periods ranged from 15 to 40 years, with an average of 25 years, while loan terms ranged from 3 to 25 years, with an average of 14 years.

- Interim Financing (Construction): On a spread over base basis, rates ranged from 95 bps to 685 bps, with an average of 394 bps. Overall interest rates ranged from 4.20% to 10.10%, with an average of 7.19%, with loan fees of 1.50% to 5.50% (average of 3.36%). LTVs ranged from 0.50 to 1.0, with an average of 0.78. Loan terms were 12 to 24 months, with an average of 18 months. Amortization was interest only.

The preceding summary of the various indices reveals the range of terms that exist in the capital markets. In a build-to-suit scenario, the overall market trends, as well as the specifics associated with a particular site or tenant, will affect the appropriate overall development terms. If a JV entity between two healthcare providers (health system and outpatient platform company or physician group, for instance) involves providing debt to the project, then the terms should be consistent with FMV and commercially reasonable given the overall transaction profile.

If a “rent constant” is being fixed in advance, then a prudent tenant and landlord will both evaluate capital market trends (and likely projections) to determine where cap rates (or the debt markets) are likely to be at the time that either the debt is secured, or the project is sold (or both). If the funding is tied to a certain capital markets indicator, then tenant and landlord should evaluate long term trends in the selected index.

Regardless of structure (negotiated rent per square foot vs. predetermined rent factor vs. rent tied to a capital markets index), the appropriate spread (and overall development profit) should be considered in the context of the various risks and responsibilities that landlord/developer versus tenant are undertaking.

This concludes Part 3 of VMG Health’s four-part series.

Footnotes:

[1] In the December 2, 2020 Final Rule, CMS provided updated and detailed guidance on commercial reasonableness (“CR”). CR is a complex topic and a detailed CR discussion is beyond the scope of this article. For questions regarding commercial reasonableness in the context of a new real estate development, please contact VMG Health.

Categories: Uncategorized

Built-to-Suit: Constructing a New Building? Transaction Structuring, FMV, and Compliance Considerations – Part 2: Credit Ratings and BTS Healthcare Assets

June 22, 2021

By: Victor McConnell, MAI, ASA, CRE, Frank Fehribach, MAI, MRICS, and Grace McWatters

*This is Part 2 in VMG’s series on transaction structuring considerations for new developments. The other parts in this series can be found here: Part 1, Part 3, Part 4.

Are you constructing a new building, on or off of a hospital campus? If so, there are unique considerations that investors, JV partners, developers, hospitals, physicians, and other parties to a new development should evaluate. For instance, if a hospital and/or a physician partner are developing a building and then leasing it to a JV entity, the associated lease rate and overall development terms will likely need to be documented as being commercially reasonable [1] and within fair market value (“FMV”) parameters. For investors constructing build-to-suits, primary concerns may revolve around analyzing the risk associated with a particular tenant. For hospitals and physician partners who are joint venturing on a development, the key analyses may involve appropriate allocation of risk, responsibility, and capital vs. non-capital contributions that each party is making to the development. If parties are sharing in development responsibility and risk, then a careful analysis should be undertaken to ensure that parties receive appropriate return given their risk, as well as their various capital and non-capital contributions.

This article will provide an overview of key issues to be considered prior to, during, and subsequent to construction of a new building. For assistance with transaction advisory, cost benchmarking, FMV analysis, commercial reasonableness opinions, or other consulting services, please contact VMG Health.

In Part 1, we covered the economics of build-to-suit projects, the rates and returns associated with their development, as well as the types of costs and fees that can be expected during various stages of these projects. Part 2, which is presented below, will cover variance in credit ratings, lease quality, and tenant risk and how these factors can influence the profitability of a project. Parts 3 and 4 will be presented separately and will cover the relationship between capital markets and BTS rates, as well as rent factors and amortization rates, and how these factors impact development terms.

Credit Ratings and Their Impact on Build-to-Suit Deals

The terms that a landlord/developer will offer a tenant in a build-to-suit scenario are affected by the tenant’s credit rating. Some build-to-suit projects include lease guarantees from parent entities (hospital systems, platform companies, etc), while others are guaranteed by a facility-specific LLC or a physician group. A credit guaranty may be a non-capital contribution to a development that should be taken into account in a JV structure (or in setting the RoC rate with the developer). In the event that a JV develops a new building, but development responsibilities and capital (or non-capital) contributions vary between the parties, then adjustments may be required (in terms of ownership percentages versus cost, or in terms of the go-forward project lease rate) to ensure that the deal structure is consistent with FMV and is commercially reasonable.

Credit ratings and tenant risk are complex topics which have been analyzed extensively within the commercial real estate sector. A “credit tenant” is defined differently by different sources. One definition is as follows: “A tenant in a retail, office, or commercial property with a long history in business, strong financial statements, or a large market presence that could be rated as investment grade by a rating agency. Because of the likelihood of honoring their leases, credit tenants are considered less risky to lease to, and developments with credit tenants as anchors are considered less risky investments for lenders.” [2]

It is worth noting that the preceding definition defines a “credit tenant” as not strictly limited to an entity with a credit rating, though some market participants do define it as such. For instance, a research paper by Sonneman and Yerke published in The Counselors of Real Estate in 2013 defined a credit tenant as “one whose bond issues fall within the investment grade levels set by one of the three major rating agencies.” [3] However, the article also defines an ideal single-tenant, investment grade lease as: being long-term with no early termination, a triple-net or absolute net structure, periodic rent increases, and featuring multiple renewal periods.

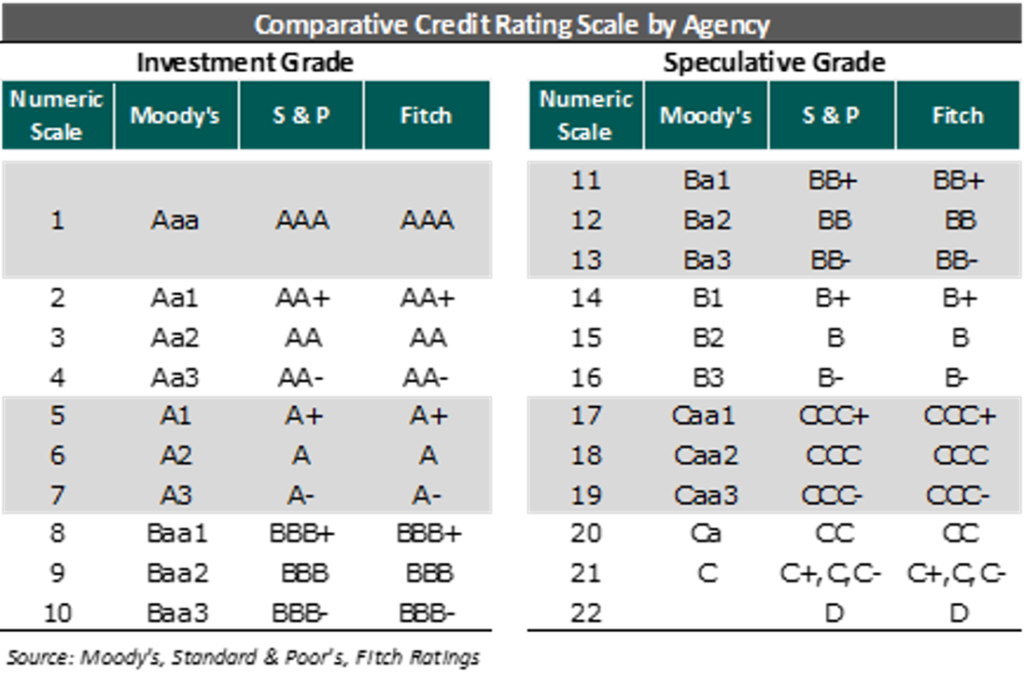

The accompanying chart (“Comparative Credit Rating Scale by Agency”) provides comparison of the credit ratings for the three main credit rating agencies: Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (“S&P”), and Fitch Ratings.

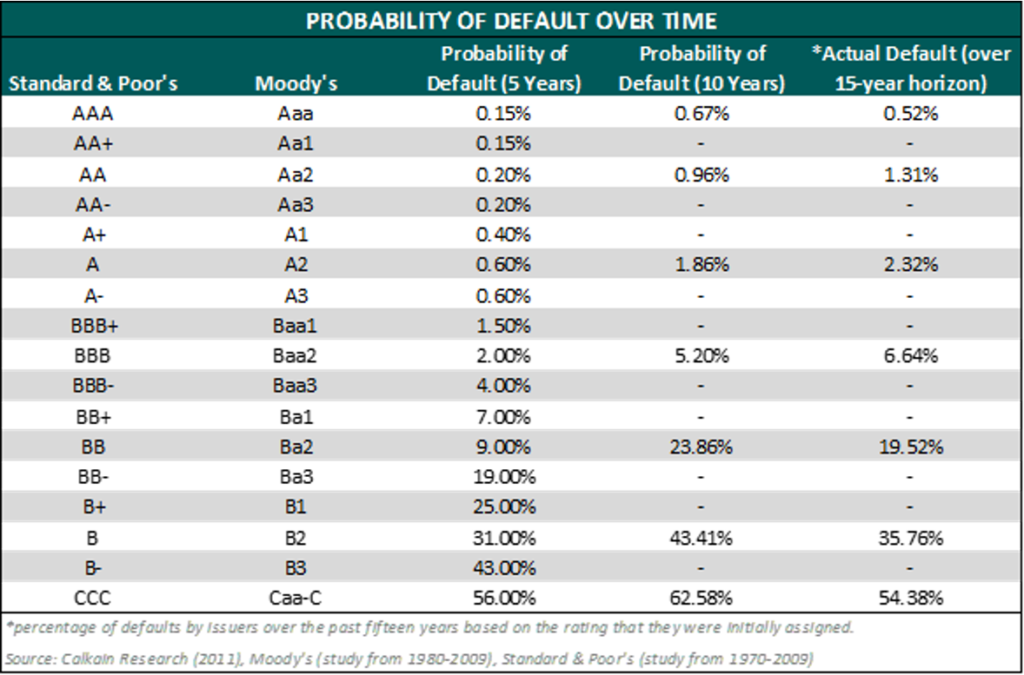

The ratings agencies have periodically evaluated their ratings relative to actual default rates and have assigned default probabilities for each rating, as summarized in the accompanying table (“Probability of Default Over Time”).

Calkain, a boutique commercial real estate firm focused in the net lease market, has a research arm which provides extensive market commentary within the net lease sector and has published numerous surveys and white papers. In a 2011 study of credit ratings and cap rates, Calkain noted that “Moody’s also measured default rates from 1970-2009 based on a company’s issued rating. At 5, 10, and 20 years, investment grade companies’ likelihood of defaulting were .973%, 2.503%, and 6.661% respectively. On the other hand, speculative grade companies over the same time horizons were 21.359%, 34.005%, and 49.649%, respectively.” [4] Entities with inferior credit ratings not only tend to default at a greater overall rate over a long period, but they also default more quickly when starting from a given point in time. For instance, Calkain’s paper also stated that “According to a study done by S&P from 1981-2009, the lower the credit rating, the faster the time of default. For example, the AAA rated companies that defaulted did so on average at 16 years from the issuance of rating, BBB and CCC rated companies did so at 7.5 and 0.9 years respectively. This shows that not only do lower rated companies have a higher probability of default, but [default] also happens at an accelerated pace with lower rating.” Within the context of the single-tenant, net-lease sector, a default likely equates to the early termination of a lease. The consequences of early lease termination depend on the lease rate relative to market as well as the risks and costs related to re-tenanting the property. Real estate investors in the single-tenant net lease sector must evaluate these considerations in their acquisition decisions. For a single-tenant, net-leased specialty asset, the cost of re-tenanting the property can be significant. In a build-to-suit scenario, a developer, lender, or investor must carefully evaluate potential downside risk scenarios in determining an appropriate RoC rate.

A paper titled “Net-Leased Single-Tenant Risks” published by George Renz in the November – December 2014 CCIM Institute publication attempted to address the question of the likelihood of a tenant actually paying rent over a 10-20+ year time horizon. [5] The paper stated that “an analysis of 100 NLST [net-lease single-tenant] deals answers the question. Out of 100 transactions with locations nationwide ranging in value from $322,000 to $9 million, only six tenants filed bankruptcy or did not pay rent. The breakdown: 1) of 70 investment-grade and national tenants, no investment grade tenants defaulted and only one national tenant defaulted; 2) of 30 franchisee, regional, and local tenants, five defaulted.” The paper provided minimal detail regarding the 100-transaction sample, and thus extrapolating any broad default probabilities would be difficult. That said, the article serves as another example of the general commercial real estate investment community’s continued attempt to evaluate risk within the single-tenant net lease sector; the activities of these market participants ultimately affect investment decisions (and, correspondingly, cap rate trends).

Other researchers have analyzed real estate lease backed securities in evaluating risk. McMurray and Mundel noted in a 1997 academic study that “for risky lessees, i.e. all lessees where there is a possibility of default in some period t < T, a credit spread must be added to the risk-free discount rate, r, in the equations shown previously.” [6] The paper noted significant risk factors impacting normative lease credit spreads including lease maturity, mean reversion, correlation, and volatility.

The purpose of discussing real estate backed securities relative to an examination of the build-to-suit healthcare real estate market is to illustrate the expansion of the buyer pool which occurs when a property features a lease backed by a credit-worthy corporate entity; properties which lack credit rated tenants could not be included within an investment grade real estate lease backed security, thus eliminating a portion of the buyer pool (institutional buyers that only invested in highly rated securities; significantly, this portion of the buyer pool typically has a lower cost of capital). If the combination of real estate, lease quality, and tenant quality is sufficient to attract institutional buyers, an impact on the property’s value (i.e. cap rate) would be expected.

In some cases with a specialty built healthcare asset (particularly on a hospital campus), the ability of a developer/landlord to sell may be subject to certain restrictions. However, even absent a sale, the risk profile associated with the lease income stream affects the debt terms achievable in the capital markets; while debt issuance is different than the sale of a property, the terms of the debt ultimately affect the developer/landlord’s profitability.

The previously referenced 2011 Calkain study noted “each lender has different criteria for who they lend to. For example, CTL [Credit Tenant Lease financing] lenders will only lend to investment tenants regardless of real estate. On the other hand, insurance companies such as American Fidelity assess all types of companies and measure them through H and Z scores to determine if they qualify. […] On [American Fidelity’s] list of approved retail credits, there were 71 retailers they would lend to and 55 not approved.” This excerpt illustrates another issue which can cause cap rate compression: superior available financing terms for properties with comparatively lower risk profiles. If a buyer can access financing at a lower rate, then it follows that the buyer would be willing to acquire the property at a lower cap rate, as the spread between the cap rate and the financing represents an arbitrage opportunity.

VMG has previously performed extensive research into the impact of credit guarantees on a variety of outpatient and inpatient healthcare assets. The impact of a credit tenant is more significant, generally, when the underlying real estate is less valuable. When the underlying real estate features strong fundamentals (i.e. growing demographic trends, high land values, strong occupancy rates, increasing rent rates, and so forth), then the impact of a credit guarantee may be diminished.

For further information concerning quantifying the value of a lease guaranty, please contact VMG Health.

The next section (Part 3) in this Build-to-Suit series involves further discussion of build-to-suits and capital markets.

Footnotes & Sources:

[1] In the December 2, 2020 Final Rule, CMS provided updated and detailed guidance on commercial reasonableness (“CR”). CR is a complex topic and a detailed CR discussion is beyond the scope of this article. For questions regarding commercial reasonableness in the context of a new real estate development, please contact VMG Health.

[2] The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 6th Edition (Chicago: Appraisal Institute, 2015).

[3] Sonneman, Donald, et al. “Comparing Value: U.S. Government Office Leases vs. Credit Tenant Leases.” The Counselors of Real Estate, Spring 2013, Vol. 38, Number 1, pp. 20-30.

[4] Caswell, Chris. “Credit Rating Effect on the Marketplace” Calkain Research, reviewed by David Sobelman, Stanley Wyricz, Richard Murphy, Michael O’Mara, Orzechowski, Winston. 2015, pp. 1-15.

[5] Renz, George L. “Net-Leased Single-Tenant Risks.” CCIM Institute, November│December 2014, pp. 22-25.

[6] McMurray, John P., Samuel M. Mundel. “Real Estate Lease-Backed Securities.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology, September 1997, pp. 1-84.

Categories: Uncategorized

Built-to-Suit: Constructing a New Building? Transaction Structuring, FMV, and Compliance Considerations

June 22, 2021

By: Victor McConnell, MAI, ASA, CRE, Frank Fehribach, MAI, MRICS, and Grace McWatters

*This is Part 1 in VMG Health’s series on transaction structuring considerations for new developments. The other parts in this series can be found here: Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.

Are you constructing a new building, on or off of a hospital campus? If so, there are unique considerations that investors, joint venture (“JV”) partners, developers, hospitals, physicians, and other parties to a new development should evaluate. For instance, if a hospital and/or a physician partner are developing a building and then leasing it to a JV entity, the associated lease rate and overall development terms will likely need to be documented as being commercially reasonable[1] and within fair market value (“FMV”) parameters. For investors constructing build-to-suits, primary concerns may revolve around analyzing the risk associated with a particular tenant. For hospitals and physician partners who are joint venturing on a development, the key analyses may involve appropriate allocation of risk, responsibility, and capital vs. non-capital contributions that each party is making to the development. If parties are sharing in development responsibility and risk, then a careful analysis should be undertaken to ensure that parties receive appropriate return given their risk, as well as their various capital and non-capital contributions.

This article, which is presented as a four-part series, will provide an overview of key issues to be considered prior to, during, and subsequent to construction of a new building. For assistance with transaction advisory, cost benchmarking, FMV analysis, commercial reasonableness opinions, or other consulting services, please contact VMG Health.

PART 1: Overview, BTS Economics, and Development Risk & Responsibility

Build-to-Suit – What is It?

The term “build-to-suit” (“BTS” or “built-to-suit”) is not formally defined within The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal; however, the Commercial Real Estate Encyclopedia defines it as “a type of real estate transaction where a property owner or developer will construct a building for sale or lease that will be built to the tenant’s or buyer’s specifications.” Within healthcare settings, developers commonly develop buildings for tenants who will then lease the building subsequent to construction. In some cases, a hospital (or JV between a hospital and a physician group) may develop a new building and then master lease it to an operating entity. In other cases, the building may be constructed by a third party (developer, REIT, private equity, etc.) who will then lease the space to a healthcare tenant.

Economics of a Build-to-Suit

In a typical build-to-suit arrangement that is to be 100% leased by a single tenant, a developer will construct a property that the tenant will lease at a percentage multiplied by the developer’s “all-in” [2] cost. Market participants differ in the terminology utilized to refer to this “build-to-suit rate”; common terms include return-on-cost (“RoC”) rate, initial yield rate, rent constant (or factor), development constant, or developer’s yield.

In these arrangements, a developer receives a return via the rent collected over the course of the lease term, as well as via reversion upon project sale (unless there is no residual, in which case a developer achieves their targeted return via rent collected during the holding period). The developer will generally anticipate selling the property at an overall capitalization rate (“cap rate”[3]) that is below the build-to-suit rate. Factors which can affect the RoC rate are similar to factors which affect cap rates. These factors include, but are not limited to: a) tenant creditworthiness; b) financing terms associated with the transaction; c) length of lease term; d) lease escalations; e) a property’s location and physical characteristics, such as design and construction quality; f) expense structure between tenant and landlord; g) renewal probability; h) anticipated reversion; i) trends in the capital markets; j) industry specific trends; k) landlord and tenant motivations; and l) a property’s construction cost and implied lease rate relative to market.

Some developers build and hold projects over a long period, while other seek to sell projects based on a shorter forecasted hold period [4]. Furthermore, the developer is likely borrowing money both during the construction period (an interim construction loan) as well as subsequent to construction (permanent financing). In these cases, the developer will likely anticipate borrowing at a rate that is a certain number of basis points below their build-to-suit rate. Similarly, if a landlord is providing funding for tenant improvements in an existing building, the landlord will typically provide those funds to the tenant at a rate above the landlord’s cost of borrowing. When offering tenant-specific tenant improvement (“TIs”) allowances, a real estate investor will evaluate how much residual value, if any, will remain at the end of the lease term. If the TIs are highly specialized and tenant specific, an investor may seek to amortize the full cost of the TIs into the lease term, as the likelihood of residual value to another tenant is low. In some cases, a landlord may offer an amortization schedule which exceeds the lease term, although the tenant may be required to pay the unamortized cost of the TIs if they choose not to renew the lease.

In structuring a lease associated with a build-to-suit, the overall economics must be carefully considered in order to ensure that each party is receiving a return commensurate with their risk and responsibility.

Evaluating Build-to-Suit Rates

Build-to-suit rates (i.e. rent constants) are highly correlated with cap rates and other capital market indicators. However, specifics concerning lease structure (such as absolute net vs. triple-net) can also affect an appropriate rent constant. For instance, in an absolute net lease structure, a tenant will bear more ongoing capital expenditures during the lease term, which decreases the risk profile for the landlord. Term length also affects an appropriate build-to-suit rate, as longer terms are generally more favorable to landlords due to lowering risk profiles (which can translate to lower cap rates or superior financing options).

VMG has conducted extensive research into cap rate trends across various healthcare real estate asset classes. In the course of our valuation and consulting work pertaining to proposed projects, VMG Health has also interviewed multiple investors, developers, and brokers active in the healthcare real estate market regarding cap rate and build-to-suit data for various assets. While return-on-cost rates offered by build-to-suit developers generally compress along with overall capital markets trends, historical averages for a particular sector, as well as forecasted risks for a particular tenant (and their associated industry) will affect the build-to-suit terms available at any given time.

Cap rates and RoC rates are different, though correlated. As previously noted, when developers build specialty healthcare assets for tenants on a build-to-suit basis, the developer’s profit is often a function of the “spread” between their RoC rate and their exit cap rate. For instance, as noted previously, if a developer constructs a project at a 9.0% RoC rate and then immediately sells the project for an 8.0% cap rate upon completion (a 100 BPS spread), the developer will have made a 12.5% unlevered profit (without considering timing and other certain factors). A project built at a 7% RoC and sold at a 6% cap rate would represent a 16.7% unlevered profit for the developer.

In addition to the project-specific or tenant-specific risk factors which can affect risk and profit expectations, the size of the development can also affect the spread sought by the developer, as developer profits tend to be smaller on a percentage basis for a $50 million project as compared to a $5 million project.

Ultimately, build-to-suit rates and development profit are largely affected by the risk associated with the tenant, as well as with the risks and responsibility allocation between developer and tenant.

Tenant risk will be discussed later in this article, whereas an overview of development risk and responsibility is presented in the following section.

Development Risk and Responsibility

In constructing a new real estate development (or performing significant renovations on an existing building), a number of different direct costs [5] and indirect costs [6] are required. Furthermore, time and expertise are required to manage various parts of the construction process. Developers also commonly take a variety of risks during the development process, and the overall return achieved by a developer is generally considered to represent compensation for the risk taken on by the developer. There are a wide array of potential risks (and time expenditures) that a developer may incur, including items such as, but not limited to, the following: a) market analysis and feasibility studies to assess demand prior to development; b) site selection and land acquisition, including potential negotiations with multiple sellers to assemble a large development tract; c) environmental assessments; d) site plans, permitting, and building plans; e) zoning analysis and applying for zoning changes or use exceptions; f) infrastructure assessment and improvement; g) construction financing; and h) other factors. A developer must also consider and factor in the potential for project failure at various points in the early stages, which could result in significant financial losses for the developer. The early-stage land development process can be delayed by a variety of factors, including environmental issues, design delays, zoning and entitlement delays, appeals (and/or litigation) from nearby property owners or other interest parties, and disputes between a developer and the local municipality or other regulatory authorities. During the construction process, a developer may also face risks associated with construction delays, cost overruns, financing issues, pre-leasing risk, and other factors. Subsequent to completion, a developer may continue to have various risks in a project, depending on lease-up, potential exit strategy, tenant default, property management, ongoing capital expenditures, and other considerations.

Given the extended timeline in which development risk is incurred, the timing of an equity investment in an LLC which owns a new building affects the way in which the ownership interest is valued. Assuming an investment is made at very beginning, when the proposed project is just a plan, then the pricing for an equity buy-in into the real estate ownership entity may correspond more closely to direct cost and indirect cost of the development. This is because all investors paying for the construction of the project are sharing in the risks of the project’s development. This assumes that project risks are shared evenly and equitably among JV partners; in these cases, a project’s entrepreneurial profit/incentive would generally align accordingly.

When a project is complete, the sale of a minority equity position (or the sale of a 100% ownership position) in the project will generally no longer correspond as closely to the aggregate construction costs, as the development risk has already been incurred. Thus, post-completion, equity positions should generally be based upon their fair market value (because the equity investor post-completion is no longer taking on development risk and thus would not reasonably be expected to participate in the entrepreneurial profit/incentive associated with the development).

A real estate development can involve a developer and a variety of individuals or companies responsible for managing or overseeing components of a project. Within commercial real estate development, developers are sometimes hired on a fee for development basis, with developer’s fees often included within a project’s budgeted soft costs; this generally represents a lower risk profile for a developer. Developer’s fee is defined as follows: “typically, a payment by a property owner to a third party for overseeing the development of a project from inception to completion, included among the direct and indirect costs of development. Sometimes, the term is used to describe the time, energy, and experience a developer invests in a project as well as a reward for the risk undertaken.” [7] Developer’s fee is distinct from “developer’s profit”, which is defined as “The profit earned by the developer of a real estate project.” Developer’s profit is also sometimes referred to (by appraisers and real estate analysts) as entrepreneurial profit, and the two terms can represent the same concept, though certain market participants may apply the terms differently.

Entrepreneurial profit is defined as: “A market-derived figure that represents the amount an entrepreneur receives for his or her contribution to a project and risk; the difference between the total cost of a property (cost of development) and its market value (property value after completion), which represents the entrepreneur’s compensation for the risk and expertise associated with development.” Entrepreneurial incentive is defined as: “The amount an entrepreneur expects to receive for his or her contribution to a project. Entrepreneurial incentive may be distinguished from entrepreneurial profit (often called developer’s profit) in that it is the expectation of future profit as opposed to the profit actually earned on a development or improvement.”

It should be noted that, over a large enough sample, entrepreneurial profit and entrepreneurial incentive should be roughly equivalent. However, as illustrated by the definitions, entrepreneurial profit is a historical fact (based on the actual profit achieved), whereas entrepreneurial incentive is based on profit that is anticipated.

Entrepreneurial profit (or developer’s profit) and developer’s fees are separate and distinct from certain other soft costs, such as “contractor’s overhead” and “contractor’s profit.” Contractor’s overhead is defined as “The general and administrative costs, over and above the direct costs of material and labor, that are estimated by a contractor on any construction work.” Contractor’s profit is defined as “The amount by which the fee received by a contractor for work performed exceeds the total direct costs of material, labor, and overhead. [8]

Developer’s profit can include construction management and project management, as well, though construction management and project management are not defined terms within The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal. [9] However, both are required to construct a building and are roles that are often filled by the developer or the general contractor. Pricing for these services can vary and depend, in part, on whether the party providing the service is profiting in other ways from the development (e.g. a developer who is also the owner or landlord). If a developer is overseeing a project but is not contributing equity, then a developer will typically charge a fee for their time and expertise. If a developer is contributing equity or going at risk for other project components, they may price certain fees differently as they will likely evaluate their overall return on a project relative to the risk (and required time, expertise, and capital outlay). Furthermore, as noted, some developers may provide services on a fixed fee basis, while others will provide services as a percentage of costs or as part of their overall project role (e.g. a developer with significant risk and equity in a project may expect to provide a variety of services over the development and construction lifecycle). Thus, in some instances, developer’s pricing and compensation may also implicitly or explicitly reflect brokerage fees [10], site selection [11] services, or other items.

The detailed discussion of various risks and responsibilities involved in the development process is presented in order to illustrate the complexity of allocating risk and responsibilities between parties in a build-to-suit transaction (and ensuring that the transaction structure appropriately accounts for these factors).

If you are evaluating a potential build-to-suit project and require third-party expertise to assist with ensuring that the transaction structure is fair and reasonable to each party participating in the development, please contact VMG Health for assistance.

The next portion (Part 2) of this series will focus on credit ratings and their impact on build-to-suit projects.

Footnotes:

[1] In the December 2, 2020 Final Rule, CMS provided updated and detailed guidance on commercial reasonableness (“CR”). CR is a complex topic, and a detailed CR discussion is beyond the scope of this article. For questions regarding commercial reasonableness in the context of a new real estate development, please contact VMG Health.

[2] “All-in” costs may be defined differently by different developers for different projects in different markets. Developers take different approaches to pricing projects in a competitive bid situation, with some shifting more profit to a projected residual, while others may seek a higher developer fee or higher rent rate. Generally, however, “all-in” costs encompass all of a developer’s hard and soft costs, including land acquisition, building design and construction, site work, project financing, and so forth.

[3] A “capitalization rate” is defined by The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal as “a ratio of one year’s net operating income provided by an asset to the value of the asset; used to convert income into value in the application of the income capitalization approach.” Within the single-tenant, net-leased sector, there are slight variances in the methodologies by which investors calculate a capitalization rate. A detailed discussion pertaining to these variances is beyond the scope of this article.

[4] A hold period, or “holding period”, is defined as “the term of ownership of an investment”. Source: The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 6th Edition (Chicago: Appraisal Institute, 2015).

[5] Direct costs are defined by The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal as “Expenditures for the labor and materials used in the construction of improvements; also called hard costs.”

[6] Indirect costs are defined in The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal as “Expenditures or allowances for items other than labor and materials that are necessary for construction, but are not typically part of the construction contract. Indirect costs may include administrative costs, professional fees, financing costs and the interest paid on construction loans, taxes, the builder’s or developer’s all-risk insurance during construction, and marketing, sales, and lease-up costs incurred to achieve occupancy or sale. Also called soft costs.”

[7] The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 6th Edition (Chicago: Appraisal Institute, 2015).

[8] Ibid.

[9] An example of a definition of “construction management fee” sourced from lawinsider.com is noted as the “fee or other remuneration for acting as general contractor and/or construction manager to construct improvements, supervise and coordinate projects or to provide major repairs or rehabilitation on a property.”

[10] When acquiring vacant land for development or buying, selling, or leasing a building, fees are often paid to a third-party broker based upon a percentage of sales or lease price. Brokerage fees (i.e. broker’s “commission”) are defined by The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal as follows: “an agent’s compensation for performing his or her duties; in real estate, a percentage of the selling price of property or a percentage of rentals that is received by the agent.”

[11] Some developers perform site selection services in conjunction with other development services. Brokers will also assist in site selection as part of their brokerage services in assisting a client in buying a property. Furthermore, consultants who specialize in site selection and appraisers with expertise in site selection are sometimes separately engaged in evaluating a potential new location, though their services can sometimes include a more comprehensive feasibility analysis. In some cases, the company providing site selection services will also be involved in conducting feasibility studies and/or limited negotiation with the seller of the land.

Categories: Uncategorized

Survey Says: The Time to Evaluate Your Market-Based Physician Compensation Plan Designs Is Now

June 16, 2021

Written by Anthony Domanico and Ben Minnis

With the COVID-19 pandemic impacting compensation and productivity levels in 2020, significant changes to wRVU values in the 2021 Medicare physician fee schedule, and the continued industry move from volume to value-based reimbursement and compensation models, VMG Health previously recommended a cautioned approach to compensation surveys in 2021, 2022 and potentially beyond. While it is still early in the 2021 survey season, recently published surveys serve as a strong case study as to why caution is the best approach.

Take the example of family medicine in the 2021 Medical Group Management Association (“MGMA”) survey. VMG expected to see a sizeable decrease in the level of reported work relative value units (wRVUs), which went down by 11.1% at the median from 2020 to 2021. What we did not expect was a nearly 4% increase in median compensation for the specialty, resulting in a 15.5% increase in the reported ratio of compensation per wRVU.

In fact, in reviewing some of the most commonly employed specialists in the market, compensation per wRVU ratios increased between 10 and 12% for primary care, medical, and surgical subspecialties. The only specialty group with a typical 2-3% level of increase are hospital-based specialties, which were less susceptible to changes in volume during the pandemic.

A Closer Look at Family Medicine

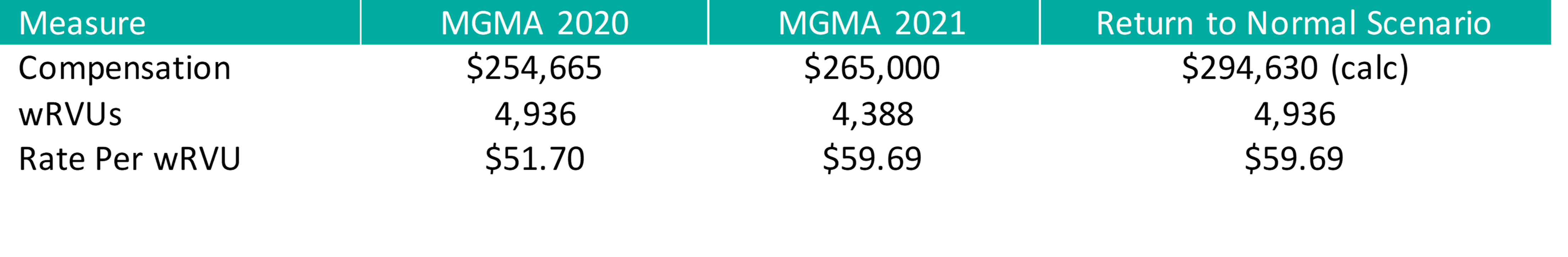

The MGMA median compensation for Family Medicine in 2020 was $254,665, with median wRVUs of 4,936 and a median compensation per wRVU rate of $51.70. The 2021 median compensation is about $265,000, a nearly 4% increase from 2020.

If it is assumed that wRVUs performed in calendar year 2021 will return to 2019 levels (ignoring, for now, the change in wRVU values in the latest Medicare fee schedule), at a median rate of compensation per wRVU of $59.69 in the latest survey, the calculated compensation for someone producing at the 2019 median wRVU level would be $294,630 (4,936 x $59.69), a 15.7% increase from 2019 median compensation.

Table 1 – Return to Normal Scenario (Family Medicine)

A similar impact would be found for most of the most commonly employed physician specialties, leading to a potentially significant increased spend in physician compensation for organizations with compensation levels tied to wRVU productivity using conversion factors per the latest industry surveys.

Double Whammy: The 2021 CMS Physician Fee Schedule

It would be one thing if the COVID-19 impact was the only issue impacting physician compensation in 2021, however the increased wRVU values in the 2021 Medicare physician fee schedule complicates the issue even further. Based on our analysis of the new fee schedule, VMG expects wRVUs to increase by about 20% for family medicine physicians, from a median of about 5,000 wRVUs per FTE to nearly 6,000 wRVUs per FTE.

If an organization took the approach of using the latest Medicare fee schedule and the median conversion factor from the latest surveys without adjusting for the impact of the fee schedule, that organization would compensate a median-producing physician over $353,000 (5,923 wRVUs x $59.69), $100,000 more than the median compensation in 2020. Even a 20% reduction to the conversion factor would result in compensation of nearly $283,000 (5,923 x $47.75, which is $59.69 x 80%), an 11% increase from the 2020 median compensation level. Reductions would be less and resulting compensation higher for specialties with a smaller Medicare fee schedule impact.

Table 2 – Return to Normal + CMS Changes (Family Medicine)

Potential 2022 Market Data Solutions

While there are many ways organizations can modify their compensation plans in 2022, two potential solutions could help organizations bridge the gap until surveys stabilize over the next few years.

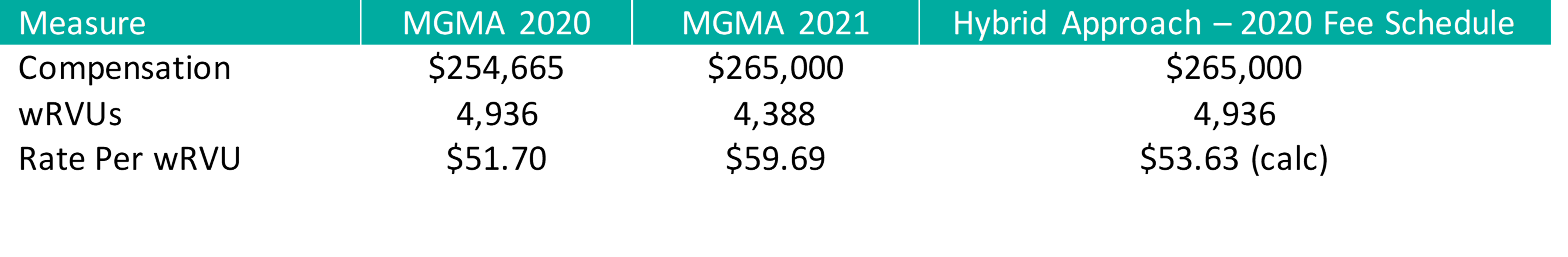

Option 1: A Hybrid Approach

Under the hybrid approach, organizations could use reported compensation levels in the 2021 surveys (e.g., a 4% increase to $265,000 for family medicine) and the 2020 survey median wRVU levels (4,936 for family medicine) to calculate a presumed median ratio of compensation per wRVU of $53.63 to be used for organizations choosing to remain on the 2020 fee schedule in 2022.

Table 3 – Hybrid Approach – 2020 CMS Physician Fee Schedule

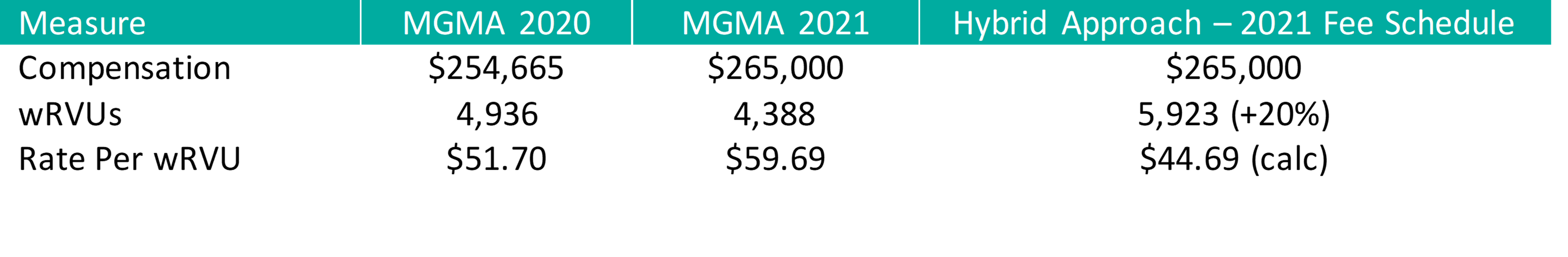

For organizations looking to switch to the 2021 fee schedule, an adjusted survey median level of wRVUs (5,923 for family medicine presuming a 20% fee schedule increase) could be used to calculate an adjusted ratio of $44.69 per wRVU.

Table 4 – Hybrid Approach – 2021 CMS Physician Fee Schedule

Under this approach, regardless of the fee schedule utilized by an organization, a physician producing at a median level of wRVUs would earn the median compensation of $265,000, and physicians would be compensated appropriately relative to their level of work effort.

Option 2: Use 2020 Surveys, with Possible Adjustments for the Fee Schedule Changes

Another option available to organizations is to simply use the 2020 surveys (based on 2019 data), with some aging factors to account for changes in compensation and productivity levels to bring the data to the current year. This approach also assumes some return to normalcy post-pandemic and assumes that compensation changes in the 2021 surveys are also unreliable (e.g., some organizations provided hazard pay or additional compensation that would not typically be earned due to the pandemic).

Other Surveys

Upon a preliminary view of the American Medical Group Association (AMGA) 2021 Provider Compensation Survey, VMG discovered very similar trends to those seen in the MGMA survey. Specifically, wRVUs for many large specialties declined significantly in 2020, causing the reported compensation rate per wRVU values to sharply increase. VMG will continue to monitor the release of other provider compensation surveys as they are published.

Summary

Until surveys more accurately reflect the sustained impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2021 CMS physician fee schedule, organizations may want to consider an alternative market strategy for provider compensation in 2021 and 2022. While there are many ways to maintain a competitive, financially sustainable, and compliant compensation program going forward, organizations will want to fully understand the impact to providers before incorporating the latest surveys.

VMG Health can help organizations develop a market data strategy as organizations consider compensation plan changes for 2022 and 2023.

Categories: Uncategorized

Location, Location, Location: Premium Sites and Healthcare Real Estate

June 15, 2021

By: Kristin M. Herrmann, MAI and Victor H. McConnell, MAI, ASA, CRE

The late Lord Harold Samuel, founder of the UK property company Land Securities, has been credited with coining the expression: “There are three things you need in property, these are: location, location, and location.” [1]

While what makes for a “good” location varies widely depending on the use, certain sites command premium pricing. Inpatient or outpatient healthcare uses located in high density, urban settings often must grapple with high underlying land values, which can affect the financial feasibility [2] of a particular use. Furthermore, in high density urban locations where the supply of potential development sites is low, healthcare users may have to compete with other buyers who intend to use a property for office, multi-family, or mixed use. Many urban locations may also feature ground leases (or be offered to the market on a ground lease basis); ground leases within urban markets are common, and the valuation considerations associated with ground leases can be complex [3], whether the site is located on a hospital campus or not.

Ultimately, when evaluating land transactions and underlying site value, it is important to consider factors such as: a) entitlements; b) assemblage/synergy; c) size/highest and best use; d) bulk zoning regulations (including floor area ratio and building height); and e) other factors related to urban settings.

This article will provide an overview of some of these considerations. For specific questions concerning healthcare real estate and premium site value considerations, please contact VMG Health’s real estate division.

Entitlements

Entitlement – “In the context of ownership, use, or development of real estate, governmental approval for annexation, zoning, utility extensions, number of lots, total floor area, construction permits, and occupancy or use permits.”[4]

In certain parts of the country, separate markets exist for entitled properties; this is primarily driven by the risk and time associated with the entitlement process. In these markets, some buyers will acquire a property, secure entitlements, then sell the property to another buyer who will proceed to develop the property. The arbitrage between these two transactions may represent the value associated with the entitlements (though other factors, such as a change in market conditions or navigating other development risks during that period, can also impact the pricing differential). The magnitude of the premium can vary widely from municipality to municipality, even within the same metro area. For instance, some municipalities are more challenging to get zoning variances in than others. If the approval timeline is twice as long in one location, then, generally, the value of a fully entitled property will be higher (assuming that the entitlements obtained are consistent with the property’s highest and best use). Legal issues (i.e., neighborhood residents suing to prevent a proposed development, or site-specific environmental challenges) can also create significant additional development risk or timing delays.

During the course of a variety of healthcare real estate valuation and consulting assignments, VMG Health has evaluated the impact of entitlements on land transactions in high cost, core urban markets across the United States.

Assemblage/Synergy

Assemblage [5]

- “The combining of two or more parcels, usually but not necessarily contiguous, into one ownership or use; the process that may create plottage value.

- The combining of separate properties into units, sets, or groups, i.e., integration or combination under unified ownership.”

Synergy – “The total effect of combining enterprises, which is greater than the sum of the independent actions combined to create the effect; in real estate, usually applied to multiuse properties in which the value of the total development is greater than the sum of the individual parts.”[6]

According to The Appraisal of Real Estate, 15th Edition, “Sometimes highest and best use results from assembling two or more parcels of land under one ownership. If the combined parcels have a greater unit value than they did separately, plottage value is created. Plottage is an increment of value that results when two or more sites are combined to produce a larger site with greater utility and probably a different highest and best use…Plottage value may also apply to an existing site of a special size or shape that has greater utility than more conventional, smaller lots. Neighboring land uses and values are analyzed to determine whether an appraised property has plottage value.”

Value premiums associated with assemblages are highly variable. In the article “Estimating assemblage value to help buyers and sellers” dated August 15, 2013, John Galvin from Andrews & Galvin Appraisal Services, LLC discusses the economic theories of supply and demand as it relates to an assemblage. “The buyer wants a specific finite product creating demand. The seller holds the only commodity that will work for the buyer creating the supply. In an active market with steady demand and supply, the two reconcile an exchange of the product in the form of a price, hence creating the current market value of that product. However, if the seller is not willing to sell, the point of equilibrium of the exchange has to shift in order to reach a point where both parties can make a satisfying exchange. For an abutting/assembling property owner, this often means a premium has to be paid to entice the seller to make the exchange… When the buyer is highly motivated to generate a return by the assemblage, yet the seller is not motivated to sell, a premium is almost always involved in the conveyance. For motivated sales, the appraiser is taxed to extract that premium in order to equate the market price paid to make a comparison… A buyer is willing to pay a premium until the point where assembly is no longer feasible.

Sometimes the “assemblage value” is not enough to entice a seller to depart with their property or property rights. One notorious example of this was the “Chicken-man” case in Downtown Hartford. In 1969, Travelers Insurance Co. offered the owner of the Connecticut Live Poultry Market on Grove Street and Columbus Boulevard a sum of $110,000 for his small retail facility. This was considered a very high price for the time period, reflecting the premium the buyer was willing to pay above the fee simple market value of the property. The owner, Dominic LaTorre, who became nationally known as the “Chicken-man,” refused to sell out on the grounds that he was essentially “standing up for the little guy.” Travelers Insurance Company ended up redesigning their class A office building around the small retail store (Hartford Courant, July 7, 1993).”[7]

Some assemblage transactions can effectively represent bilateral monopolies, whereby the only site that facilitates a particular development is held by one specific seller – yet the only realistic buyer may be an entity who has already assembled all of the adjoining parcels and is seeking to acquire the one remaining parcel. In these situations, the relative leverage of either party (along with whether it is possible to develop the assemblage absent the one parcel, as noted in the example above) can result in a wide range as compared to what would be expected in a typical transaction without any assemblage considerations.

In the article, “The Added Value of Assembling Parcels” in Right of Way magazine, the author states that “In general, applying the assemblage theory may be appropriate when the following conditions exist in the before condition:

- The costs required to assemble the land are financially feasible.

- The assemblage of parcels can be accomplished in the reasonably near future.

- The owners of the subject properties are willing to participate in the assemblage.

- It is physically possible, legally permissible, and financially feasible to achieve the highest and best use case scenario through the assemblage theory.

- The highest and best use case scenario resulting from assemblage will result in the highest value for the subject parcel.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, a recent case employed the assemblage theory. It involved the condemnation of a half-acre vacant parcel needed to expand an adjoining one-acre city-owned vacant parcel for future development as a city park. The half-acre parcel was substantially impacted by two earthquake fault-lines that traversed through it, thus limiting the potential area for future structures to approximately 900 square feet. The city’s one-acre parcel was generally not impacted by fault-lines and did not face nearly the same developmental limitations as did the half-acre parcel. Absent the park project that resulted in the condemnation, the city would not have needed the land for public use. It would therefore have been faced with not having to condemn the half-acre parcel and surplusing its one-acre adjoining parcel. It was determined by the property owner’s legal team that the joinder of the half-acre with the one-acre parcel would have resulted in the highest and best use scenario for both parcels. The combined 1.5-acre site created through assemblage would have allowed for a greater range of developable land uses, such as a fast-food restaurant or service station. These uses would not otherwise have been feasible if the parcels were developed independently. The assemblage would have further allowed the half-acre parcel to be utilized for the required parking and much of the required landscaping, thus greatly increasing its potential land value. This case ultimately settled prior to going to trial.

Therefore the assemblage of parcels and the resulting increased acreage can create certain opportunities. For example, commercial parcels containing less than a half-acre are often restricted to uses requiring limited building floor area and parking, such as retail or office. However, if assembled with adjacent land, the combined acreage may reach an area threshold that allows for additional uses, such as a fast-food restaurant or service station. Substantial additional acreage may have the potential to accommodate even more intensive uses, such as a hotel, mixed-use project or high-rise development. An increase in acreage may also justify the construction of a parking structure. From a highest and best use standpoint, parking structures allow much greater building floor area to be constructed, thus further increasing the number of potential highest and best use candidates. Whether or not to construct a parking structure of course involves many factors of which adequate acreage is an essential one.

An increase in land area through assemblage, along with the removal of the previously shared property lines, can help to lessen the impacts of certain local development standards. This in turn results in the potential for greater developmental intensity and land value. When parcels are combined, the shared property lines that separate them disappear, as do the setback requirements on both sides of those property lines. The proportionate impact caused by the setbacks on development also diminishes accordingly. For example, two five-foot side yard setbacks on a 100-foot wide parcel (ten percent of the total setback area) are far less impacting than the same setbacks on a thirty-foot wide parcel (33 percent of the total setback area) because they allow for a greater percentage of the site to be developed.”[8]

Per the working paper “Estimating the Holdout Problem in Land Assembly,” from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta dated December 2013 and written by Chris Cunningham, the author notes: “I find that properties sold before an assemblage command a statistically significant and economical large premium of 13 dollars per square foot, a seventeen percent premium relative to non-assembled land sold in the same census tract. This finding is robust to inclusion a rich set of control variables for time and space. Consistent with the game theoretic literature, the premium decreases with an individual parcel’s share of the total assemblage. Finally, parcels at the center of ultimate assembly may command higher premiums than do parcels at the edge, suggesting that developers retain, or at least are able to convince would-be holdouts that they can build around a holdout.”[9]

In some cases, an assemblage may facilitate a change in highest and best use or may allow for a zoning change. In these situations, due to the change in economics associated with the proposed development, the value of the underlying site may also change.

VMG Health has interviewed individual developers, brokers, and investors in various urban markets concerning this issue. A common theme among these interviews is the variance regarding the extent to which assemblage affects a transaction – individual examples exist of assemblage sales which seemingly occurred at no premium, and others which occurred at a price well over what the property would have otherwise sold for, if there were no assemblage. Accordingly, the appraiser or analyst must carefully evaluate individual transactions to determine whether pricing was impacted.

Highest and Best Use

Highest and best use may be defined as, “the reasonably probable use of property that results in the highest value.”[10] Highest and best use must meet the following four criteria: 1) Physically possible; 2) Legally permissible; 3) Financially feasible; and 4) Maximally productive. The appraiser’s (or analyst’s) determination of a property’s highest and best use as if vacant is key to deriving an opinion of land value.

Physical possibility is defined as follows: “[f]or a land use to be considered physically possible, the parcel of land must be able to accommodate the construction of any building that would be a candidate for the ideal improvement. [11]

Legal permissibility is defined as “a property use that is either currently allowed or most probably allowable under zoning codes, building codes, environmental regulations, and other applicable laws and regulations that govern land use.” [12]

Financial feasibility is defined as “[t]he capability of a physically possible and legal use of property to produce a positive return to the land after considering risk and all costs to create and maintain the use.” [13]

Maximally productive use is defined as “the physically possible, legally permissible, and financially feasible use that results in the highest present value.” [14]

According to the Appraisal Institute’s Advanced Land Valuation: Sound Solutions to Perplexing Problems, “if two or more uses are financially feasible, then the use that generates the highest residual land value is the use that is maximally productive and represents the highest and best use of the land.” The land residual technique, “a method of estimating land value in which the net operating income attributable to the land is capitalized to produce an indication of the land’s contribution to the total property” [15] is sometimes utilized to determine the maximally productive use (and as such, the highest and best use) for a proposed property.

Site size can affect pricing and development potential. Smaller sites may sell for higher per unit prices in some instances, though a larger site may command a higher per unit price in others, particularly if the larger site can accommodate a different array of uses. In high-density markets, slightly larger sites are sometimes considered more developable, and thus can be more attractive to a developer. In some cases, a change in site size may change the highest and best use (as discussed above), which can affect the value per square foot or per FAR. In other cases, larger sites which command a higher total purchase price may suffer from smaller buyer pools (which generally would drive down the price per square foot due to less competition).

Ultimately, highest and best use analysis is a complex topic, and the level of diligence required to appropriately assess highest and best use is project specific and site specific.

Bulk Regulations (including Floor Area Ratio and Building Height)

Bulk regulations are defined as “Zoning laws or other regulations that control the height, mass, density, and location of buildings, setting a maximum limit on the intensity of development to ensure proper light, air, and open space.” [16] Bulk regulations include limitations (both maximum and minimum) on floor area ratio, setbacks, lot coverage, building height, and required open space, among others.

Most pertinent to the discussion of high dollar land are 1) the allowable floor area ratio (or “FAR”) and 2) the maximum building height. FAR is defined as “The relationship between the above-ground floor area of a building, as described by the zoning or building code, and the area of the plot on which it stands; in planning and zoning, often expressed as a decimal, e.g., a ratio of 2.0 indicates that the permissible floor area of a building is twice the total land area.” [17] Floor area ratio may also be referred to as building-to-land ratio. In certain municipalities, the ratio of building area which can be constructed on a site, which can also be somewhat dictated by the maximum allowable building height, can be a better indicator of the value of the land than on a purely price per square foot of land area basis, since a higher allowable floor area ratio (as well as a higher allowable building height) would allow for the construction of a larger/taller building, all else equal.

The price per FAR foot can also be dependent on the allowable use for the site in question. It may not be financially feasible to develop a site to its maximum FAR, for instance – or the cash flows associated with one property use may differ from another (driving differential in price per FAR). VMG has investigated urban markets where a significant premium existed for multi-family versus office use, due to higher demand and superior projected cash flows for multi-family development (even if the allowable FAR was the same for multi-family versus office).

Bulk regulations and FAR should be evaluated carefully with regard to the subject site as well as any comparative transactions to understand the degree to which differing zoning regulations drove corresponding differences in per square foot or per FAR foot land pricing.

Factors Related to Urban Settings

In urban settings, other considerations which can affect property value (and certain associated premiums) may also include a site’s proximity to public transportation (i.e., transit-oriented development or “TOD” locations) or ingress/egress, such as is associated with corner locations.

In many large cities, commuter rapid transit options attract pedestrian traffic to railway stations. This tends to benefit properties which are in close proximity (typically within half a mile or so) to these stations, and there is often a premium for TOD locations. The extent to which this premium exists varies market to market and site to site – and, furthermore, concerns emanating from the COVID-19 pandemic (related to mass transit, as well as congregate, in-person work environments) may have affected this premium since early-2020.

Corner locations, signalized intersections, and other ingress/egress issues can also affect the pricing of urban land parcels. Visibility, exposure, and signage can all contribute to making a corner site more desirable. However, while some corner sites may sell for more than similarly located non-corner sites, in other cases, setback requirements may limit the development potential of a particular site which could offset any corner premium.

Conclusion

While healthcare providers located in lower cost markets or in suburban settings may not have to grapple with urban land valuation considerations, many hospitals, physician groups, and other healthcare users face the issue due to the densely populated, urban markets in which they are located. Some older hospitals are situated in premium locations in core urban markets – these campuses must evaluate underlying land pricing if they plan to sell or lease any portion of their hospital campus. Furthermore, when considering the acquisition or leasing of other sites in an urban market, healthcare providers and investors should be aware of some of the key factors that drive pricing in an urban setting. As previously discussed, certain valuation considerations for high dollar land include but are not limited to: a) entitlements; b) assemblage/synergy; c) size/highest and best use; d) bulk zoning regulations (including floor area ratio and building height); and e) other factors related to urban settings. Due to the complexities associated with urban land valuation, an appraiser may use techniques including, but not limited to, the land residual method, the sales comparison approach, the market extraction method, or the allocation method. The appraiser or analyst may also need to have expertise in ground lease capitalization rates, yield capitalization, residual value, and so forth. For further discussion of ground leases, please refer to VMG’s ground lease article cited below.

If you are an investor, developer, or healthcare provider evaluating land pricing (or ground lease rates) in a high cost urban market and require outside expertise, please contact VMG Health’s real estate division.

For further commentary from VMG Health related to on-campus hospital ground leases, please see the following: Under All is the Land: Ground Leases and Hospital Campuses

For further commentary from VMG Health related to financial feasibility for medical office development, please see the following: Financial Feasibility & Speculative Medical Office Building Construction

Sources:

[1] https://www.company-histories.com/Land-Securities-PLC-Company-History.html

[2] For more on the topic of financial feasibility within the medical office building (“MOB”) sector, refer to the following: https://vmghealth.com/blog/financial-feasibility-speculative-medical-office-building-construction/

[3] For more guidance specific to ground lease considerations on hospital campuses, please refer to the following: https://vmghealth.com/library/under-all-is-the-land-ground-leases-and-hospital-campuses/

[4] The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 6th Edition (Chicago: Appraisal Institute, 2015).

[5] The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 6th Edition (Chicago: Appraisal Institute, 2015).

[6] Ibid.

[7] https://nerej.com/estimating-assemblage-value-to-help-buyers-and-sellers

[8] https://eweb.irwaonline.org/eweb/upload/web_mar_apr12_AssemblingParcels.pdf

[9] https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2579904

[10] Appraisal of Real Estate, 15th Edition

[11] The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 6th Edition (Chicago: Appraisal Institute, 2015).

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Appraisal Institute’s Advanced Land Valuation: Sound Solutions to Perplexing Problems

[16] The Dictionary of Real Estate Appraisal, 6th Edition (Chicago: Appraisal Institute, 2015).

[17] Ibid.

Categories: Uncategorized

Post-COVID Hospital Guidance: Comparing Full-Year Guidance from Public Hospital Operators before the COVID-19 Pandemic and One-Year Later

June 9, 2021